If you have a Fox-body or SN95 Mustang, a 1980s GM G-body (Grand National, Malibu, El Camino, etc.) or something like an early Chevelle or a GTO, it has a triangulated four-link rear suspension. This type of suspension has coil springs and upper and lower trailing arms (also called control arms). The upper arms are angled to form the triangle that gives the suspension its name. Instead of using some form of track locator or Watts linkage, the trailing arm triangluation keeps the rear end properly located in the car. That saved the factory some money.

The system works well enough on the street, but not so well when it comes to hooking up at the drag strip, especially with big horsepower. So how do you make it work? There are three items to address: shocks, anti-roll bar, and adjustable trailing arms.

Trailing Arms and Instant Center

A triangulated four-link puts the instant center (I/C) location—the imaginary point of where the rear suspension components intersect, and the point they rotate around in a given (instant) position–way out front, often close to the engine. The instant center is also rather high; the angles of the bars can raise it somewhere above the front wheel spindle.

That’s not necessarily bad. Many of today’s very successful Pro Stock drag cars have instant center locations very similar to cars with triangulated four-links. Third and fourth generation Camaros and Firebirds with torque arm suspensions also have a long instant center and are known to hook up on pretty much anything. You’ll find that an instant location similar to stock is actually close to optimum, provided you don’t jack the body way up in the air.

The problem with some trailing arms made for Mustangs and GM’s A- and G-bodies is they tend to create a very short (further from the engine) instant center by changing the angle of the bars. That can work for a mild street or bracket car, but will make a high-horsepower car react violently at launch. Just as bad, some of the top-mount arms (ones that physically raise the upper trailing arm location on the rear end housing) have a tendency to hammer the trunk floor when you get on the throttle. Avoid these types of trailing arms for drag racing.

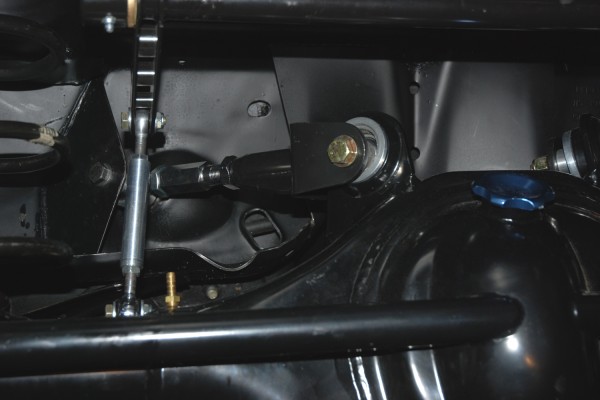

Setting Pinion Angle with Adjustable Bars

Adjustable trailing arms will allow you to set the static pinion angle. In order to keep the driveshaft and U-joints operating in a (more or less) straight line when you’re on the throttle, the pinion angle has to be correct. As the suspension in a car “wraps up”, the pinion is driven upward. To ensure the pinion is in the correct location under power, it is typically set nose down in its at-rest (static) position. Pinion angle is measured between the pinion gear flange and the driveshaft.

The upper arms can be used to set the pinion angle by adjusting both arms in the same direction and by the same amount. For cars with spherical bearings (rod ends) or solid rear suspension bushings, most racers use a pinion angle between minus one to minus two degrees (minus is negative angle, or pointing down). If the car has OEM style rubber suspension bushings, a pinion angle of minus three to minus four degrees is more appropriate.

Setting Preload

Preload is another tuning tool to counteract body roll rotation. In a high horsepower car, engine torque tends to rotate the car so the right rear tire has more bite. In turn, that bite tends to move the car toward the left. You can counteract this force by preloading the suspension. In a car with a non-triangulated four link, you can shorten the upper right trailing arm to increase the preload on the right rear tire. If you lengthen the same bar, more load is placed on the left rear tire.

On cars with triangulated upper control arms, you can’t set preload with adjustable arms. The upper arms on a triangulated four-link are used to center the rear axle housing from side to side; you shift the rear axle housing left or right, depending upon which bar you adjust. Adjustable lower bars are used to center the tires front to back in the wheel well and to make small wheelbase changes.

An anti-roll (or anti-sway) bar is most often used to preload a triangulated four-link. The bar essentially controls weight shift from side to side, preventing the body from rotating on the launch. That helps equalize traction to the rear tires.

Following the anti-roll bar, you can use adjustable shock absorbers (front and rear), front suspension limiters, and to a lesser degree, specific coil spring rates to get the car to hook up. But as you’ll see in the photos, adjustable trailing arms are the first—and best—method of setting up a triangulated four-link for drag racing.

Wayne

Dave here in Saskatoon been racing a g body for many years now and struggle to get

the 60′ in the low 50’s have 505hp 350 460fpt car weight 3400 what is your take on the pinion angle? I have tried different set ups with some success am now at 4.5 down

with the very soft chassis meaning floppy front subframe is 4.5 enough?

am out of adjustment on the uppers so will be installing a set of adjustable lowers

I hear of 305 cid stockers running in the high 1.40’s far less hp I have adjustable qa1 shocks

all the best parts

Hi Dave…Glad to help if I can. I do have a few questions though:

Are you running the car with an Anti Roll Bar or at the least, with a sway bar on the back? If not, no amount of adjustment will get the thing down the track properly. Also, how old are the shocks and have you ever had the valving checked? Bad shocks (and/or messed up valving) can be the culprit. Finally, I’m not exactly sure what you mean by a floppy front subframe. I’m assuming you’re referring to the front end – more below:

Cars with a lot of twist and bind are difficult, if not impossible to tune. To make it work, I’d be inclined to either use spherical bearing upper and lower rear trailing (control) arms or at least a set with Delrin bushings. At the nose, I’d do the same (spherical bearings or Delrin bushings). Add a good weld-on ARB out back. Get your shocks addressed (tested by someone with a shock dyno who knows what they’re doing) and then go back and work on the pinion angle, using the guidelines from the article. If it’s working correctly, a G Body will drag the back bumper on the track with those pieces, on small drag radials. Ask me how I know…L-O-L.

Hope that gets you sorted out. And have fun at SIR!

Wayne thanks for the input

I use the H&R parts stuff anti roll bar

have qa1 adjustable coil over shocks without the coil have a tube welded across the frame at the back to mount the shocks like a ladder bar

using stock coil springs new ….have adjustable uppers and

just ordered the adjustable lowers

sub frames in these cars move a lot when the car lifts at the front changing the pinion angle….. front sub frame is not tied

currently using 4.5 down and it picked up 60′

Good info!

Great info! I have a blown 71 Chevelle. 650 whp. I have edelbrock adjustable uppers with non adjustable boxed lowers. The bushings wore out in the lowers and my left tire got in the wheel tub. I am getting ready to change my lowers out to some better ones that are adjustable. Which ones do you recommend? I also have a trz weld in style arb.

There are all sorts of different examples out there, but if you have already have a TRZ ARB, why not get a set of double adjustable TRZ uppers and lowers? From personal experience, they’re great quality. Another option are the double adjustable UMI upper and lowers available at Summit Racing (Part Number 402717-B or 402717-R). Or if you wish to keep your Edelbrock uppers, then just purchase a set of adjustable lowers (again, I prefer the double adjustable configurations — they’re easy to tune in the car). UMI part numbers are 4023CM-B or 4023CM-R.

Hope this helps!

Thanks so much! Followed your advice and got a set of adjustable lowers. Now on to getting everything adjusted out and working.

I would like know what the ic would be on a g body with a 9 inch in the rear with stock suspension. Has boxed lowers, adjustable uppers , stock springs and shock. Also has a anti roll bar added to it. It’s on a car that I’m helping with. Also pinion angle with stock bushings. Has gone 1.29 60 ft on spray, has 28 10.5 et street tires on it also.

Matt,

I am setting up a GM A body 1972 Monte Carlo. The rear will have Viking coil over shocks . My trailing arms are stock triangulation. My rear end is a nine inch ford with the large pinion. I am dropping my ride height 2”. My upper a arm is at a 10 degree angle pointing down towards the front. My lower trailing arm is level. I am settling 1100 hp LS Irwin turbocharged in it. Do I need to change my angles on my trailing arms to get forward bite?

Wayne

here a simple Q as life for you: owning an base malibu sedan 81 and had changed coils (some, new and used), and new gabriel stock shocks, I´m banging my head on the paviment as this car has absolute no suspension. it feels as a plank over nude bearings on the road .. I want just for street use, nothing but just Soft Ride. What is wrong ?

Wayne

here a simple Q as hope life for you: owning an base malibu sedan 81 and had changed coils (some, new and used), and new gabriel stock shocks, I´m banging my head on the paviment as this car has absolute no suspension. it feels as a plank over nude bearings on the road .. I want just for street use, nothing but just Soft Ride, floating kind of .. What is wrong ? All driving train actually repalced with Moog components.. It seems not being an Irak/bu .

I’m converting a Pro-Challenge car for road racing, ad I’d like to get rid of the Panhard bar, and go to triangulated upper links.

The difference is, I’d like to use the center post where the three link top link currently attaches to the chassis, and go out to brackets at the ends of the rear axle. Just opposite of what’s pictured here.

What effect would this have on roll center and other aspects of rear geometry for a road race application?

Thanks in advance,

David

The pinion angle is not measured between the pinion gear flange and the driveshaft. That measurement is the rear u-joint operating angle. The pinion angle is measured between the rear of the transmission output shaft and the front of the pinion gear shaft. The driveshaft angle is measured on the side of the driveshaft tube.

ive a 70 ls 6 ss chevelle . it pulling around 1000 hp out of a 572 motor. ive a chris alston rear and front suspension with original 12 bolt poisi 4:10 ( which will be replaced at later date with 9 ” ford.) its a show car with usage on track but also drive on the street at times. right now body is off the frame. at the time i didnt think about ride height so did not record it. the alston suspension on rear is 5823-a20,5826-a10, 5824-a10.iam running b f goodrich 335/30zr18 on rear and front 245/40zr17. just so you have the whole picture. I also have a tremec 6 speed magnum. iam not a suspension specialist . So ive got to learn the hard way i guess. i just cant afford everyone to work on it because of money situation plus i need to know how to work with it when time comes for that. cant run to everyone when at track. iam older so long drawn out comment’s i loose out on meanings’ How do you set up one part before you do another .what should i work on first ,and how is it done. i want to adjust the alston first i guess , then set my ride height but i guess that involves the suspension also. then i guess try to set up after i get drive pinon angle figure out???Do you think you can help me in a few words with what info ive given you. I do need to know how to work it myself. thank you in advance if you can. i really dont want this aired on online as i wouldnt know how to recover it. my email is a good one