(Image/Wayne Scraba)

There are many questions related to adjusting tire pressure on a drag car, and it seems everyone has a different opinion.

The reality is, every car will require a slightly different tire PSI regimen, but according to chassis builder Jerry Bickel, there are some basics you can use in order to reach your baseline.

Bickel always starts with the front tires and then adjusts the rear after.

NOTE: The following tire-pressure adjustment tips are specific to drag tires. Other tires, like street car radials, will react differently to the same PSI. Additionally, track temperature affects how much heat you should put into the tires during the pre-stage burnout (which we’ll go into with more detail later in this article).

Tips for Adjusting Front Tire Pressure

“The more air you run in your front tires, the quicker your car will lift out of the staging beams, but don’t exceed the tire manufacturer’s maximum recommendation,” Bickel said. “This can help your reaction times and reduces rolling resistance.”

“One exception to the high front-tire pressure rule has to do with irregular track surfaces. Hard inflated tires may jump off a bump and cause some loss of directional control. Lowering the tire pressure a couple of pounds will often help minimize this problem. You can expect slightly higher driver reaction times and somewhat increased rolling resistance as a result of this adjustment.”

Tips for Adjusting Rear Tire Pressure

The inflation pressure you should use for slicks depends on vehicle weight, tire type (radial or bias ply), and wheel width, among other things.

“The wider the rim, the more tire inflation pressure you need. The narrower the rim, the less inflation pressure you need,” Bickel said. “With flexible sidewall drag slicks, the normal pressure range is 4-12 PSI. Check with your tire supplier and talk to some successful racers in your class to find a good starting point.”

“Drag slick inflation pressure must be exactly the same in both tires on every run. Remember that all tires leak slightly. To make sure your tires are not under-inflated for a run, add a little extra pressure before driving your car to the staging lanes. Bleed the tires down to the correct pressure just before the car enters the water box.”

Pressure Gauges, Tire Covers & Towing Tips

Common low-pressure gauges such as this aren’t 100% accurate (no secret we’re sure). What you need to do is to compare your gauge against a standard at a major race tire service truck (typically they turn up at large National events scattered across the country). On a similar note, never use two different gauges to check tire pressure on your car. You can get fooled. (Image/Wayne Scraba)

1. Always use the same tire pressure gauge, and know its variation from the standard

Low-pressure tire gauges can lose calibration easily.

There can be upward of 25-percent variation between tire gauges. That’s why smart racers will always use the same gauge (no two may read the same). If you’re at a large event and there is a drag tire service truck in attendance, you can check your gauge against their standard. That will tell you the variation in your gauge.

2. Use tire covers in the staging lanes

Air (like other gasses) expands when temperatures rise, which is why tire covers are so important. You should always use tire covers on any tires exposed to direct sunlight while waiting in the staging lanes. This will prevent the sun’s rays from heating the tire and increasing its tire pressure.

NOTE: Don’t forget that white or light-colored tire covers will reflect sunlight rather than absorb it, which is why you should use them.

3. When towing, overinflate drag slicks to remove sidewall wrinkles until just before the race

When you tow your car, add enough air to the drag slicks to remove the wrinkles from the sidewalls. This will help prevent the development of sidewall distortions and stress cracks. Inflate both tires to the same pressure and don’t exceed the maximum recommended by the manufacturer. This will prevent tire rollout changes from happening while the car is in transit.

What to Do When Track Temperatures Change

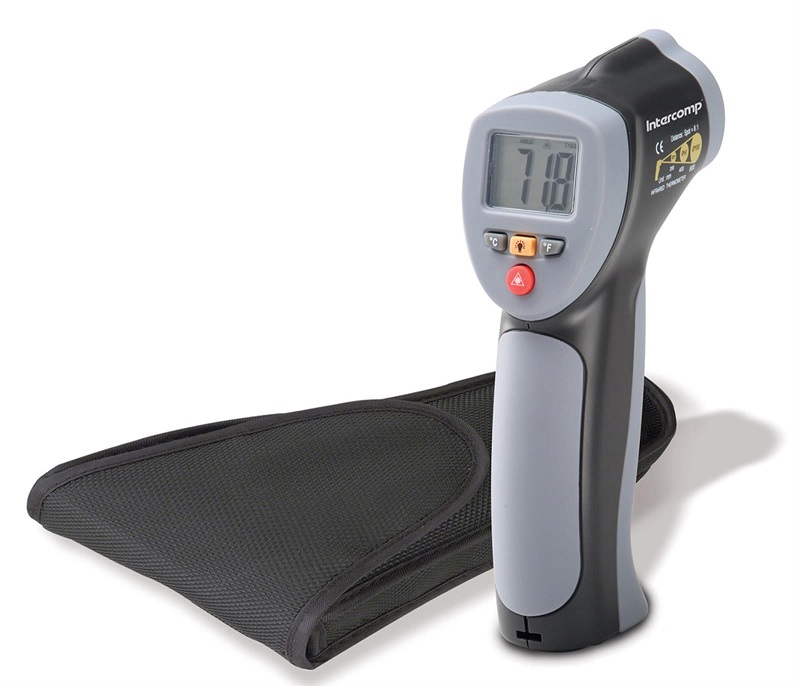

There are several different types of laser heat guns. A great example is this model from the folks at Intercomp. These infrared guns are available in a regular gun style with a pouch and in a mini version. Both read in Celsius and Fahrenheit in .1-degree increments with an accuracy of +/-2 percent. The range is from -52 below zero all the way up to 1022-degrees F. (Image/Summit Racing)

We’ve all watched racers use infrared gun to measure track temps and tires. The big advantage of this piece of equipment is that you don’t have to make physical contact between the gun and object you’re checking.

Pro tip: After the burnout, check and record both the track and tire temps. While the data you log won’t help with the immediate pass, you’ll know before the next round whether you should put more or less heat into tire with the burnout.

Bickel groups track temperatures in four ranges, and there are considerable differences in the traction characteristics among the four.

- Cold (below 90 degrees F)

- Cool (90 degrees to 105 degrees F)

- Warm (106 degrees to 130 degrees F)

- Hot (above 130 degreees F)

“Never assume that the temperature of the track is the same as that of the surrounding air,” Bickel said. “The dark color of the racetrack pavement absorbs sunlight, quickly heating the surface. Unless there is a heavy cloud cover, daytime track surface temperatures will be about 20 degrees F to 30 degrees F higher than that of the ambient air.”

The 4 Temperature Zones for Dragstrips

Here’s Bickel breakdown on all four temperature zones:

Cold Track (Below 90 degrees F)

“While the general rule of thumb for track temperature is the cooler the better, there is a point at which the available traction diminishes,” Bickel said. “If the track temperature falls below 90 degrees F, conditions can become rather tricky. You should closely monitor the runs made by cars in front of your and be ready to make whatever charges time allows. Below 75 degrees F, you can expect significant traction difficulties, especially if water has begun to condense on the surface.”

“Cold track temperatures really cool off the tires quickly. Ask the driver to make a hard burnout to put as much heat into the tires as possible. Once the burnout is complete, your goal should be to get the car to the starting line as soon as possible.”

Cool Track (90-105 degrees F)

“This is the most desirable surface temperature range for most racetracks. If the track surface also has a good cover of rubber, it will usually take all you can throw at it,” Bickel said. “Be aggressive with all aspects of the engine, clutch, and chassis tuning. If the air is dense and the surface is smooth, you should be rewarded with the best times of which your car is capable.”

Warm Track (106-130 degrees F)

“At these temperatures, the rubber on the racetrack begins to soften and pull loose from the surface. It is in this range that a quality chassis tuner begins to shine,” Bickel said. “Excellent runs are still possible if you don’t overpower the surface and pull the rubber up. Softer clutch engagement and chassis settings are the key, but your need to gather a lot of experience with your car to find out how to take just enough out of the car without compromising performance.”

Hot Track (above 130 degreees F)

“This is the hot summer range where everything seems to wilt and the fun of racing becomes a little harder to find. High temperatures take their toll in a number of ways, not the least of which is on sunbaked drivers and crewmembers,” Bickel said.

“Expect greasy track conditions and reduced engine power from the thin air. Available traction will bottom out somewhere between noon and 5 p.m. [which is usually when eliminations are running],” Bickel said. “This is no time to try to impress the world with the performance of your car; in these conditions, almost everyone has enough horsepower to win. Your challenge is to avoid overpowering the track at all costs and get to the finish line ahead of your competition.”

Burnout Tips

“Remember the goal of the burnout,” Bickel said.

“Tire manufacturers recommend that you heat the slicks to 30 degrees F higher than the track temperature. Take all race day conditions into account. The final tire temperature after completion of the burnout varies with the ambient (outside) air temperature, track temperature, and the burnout length,” Bickel said.

“Sometimes a mishap occurs on the racetrack that halts the action. If your run is stopped for any reason after a burnout, your tires (will) gain pressure. There is no reliable means to determine exactly how much heat is still in the tires. The best option you have is to assume that the first burnout never happened. Reset the air pressure in the tires again before entering the water box and then conduct a normal burnout,” Bickel said.

“A well-adjusted racecar will come straight out of the water box on the burnout and lay down nice, straight rubber tracks for the run. If your car comes out sideways, it is not only dangerously out of control, but it will lay down rubber tracks that are skewed and useless,” he said.

“The wheel weight distribution affects how straight the car will come out of the water on the burnout. This works the opposite way from what happens on the actual run. If the rear end starts going to the right out of the water, you have too much right rear bite and you need to “take spring from” (loosen) the left front. If the car goes to the left out of the box, it means you have too much left rear bite and you need to “add spring” to (tighten) the left front.”

There’s much to consider.

Reading the track, working the tire pressure (to your advantage), and making the car work as the track heats up can spell the difference between going rounds or becoming a first round runner-up.

It all adds up.

[…] Tire pressure […]

Learning, Been Watching for years, bought 71 vega panel does 9.6 quarter. Learning from your posts,So much to know keep it up. Never Drag Raced Before

Depends on how you store them and the amount of runs on them