It should come as no surprise to anyone reading this that torque wrenches are calibrated and that calibration should be checked, at least occasionally. According to some experts, torque wrench readings have a tendency to change following 2,500 to 2,800 repetitions. This can also be accelerated by improper storage (for example, not keeping the torque wrench in the case when storing it, allowing it to drop to the ground when using it, not taking the tension off the wrench when in storage and so on). The main reason for this is because most clickers are constructed with internal springs and those springs can lose tension (and lose length) over time.

Fair enough. But how can you check the calibration? Obviously, you can send it away and have a specialist check the calibration and then recalibrate the wrench. Or you can check the calibration yourself. Obviously, a DIY approach might not be quite as accurate as one that’s done in a lab environment, but it’s not that costly either. Nor is it really difficult. There are a lot of different ways to check the calibration and there are a lot of different methods to adjust some torque wrenches. Here’s one way to accomplish it (again, keeping in mind there are numerous methods out there).

How to Check Torque Wrench Calibration at Home

For something like an 18 inch wrench such as the older torque wrench shown in the accompanying photos, measure back from the square drive to the center of the handle (15 inches from the square drive in our example) and mark the handle. This is a reference number. Write it down.

Mount the square drive in a bench vice, positioning it so the handle extends outward and is pretty much horizontal. Don’t overtighten it, but be sure there’s sufficient vice tension to hold the wrench in check. Basically, you want to set this up so that the wrench can move when weight is applied to the handle, but with sufficient clamping power so that it will not fall out of the vice jaws.

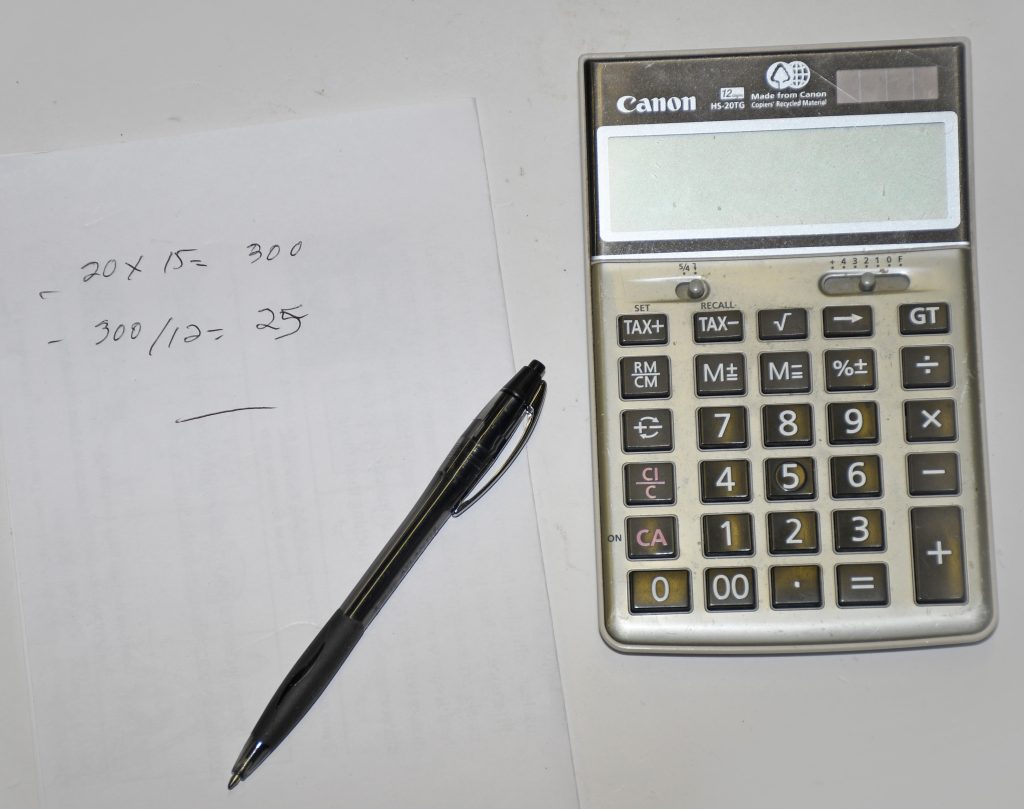

Next tie a known amount of weight to the torque wrench at the marker on the handle (15 inches in our case). The idea here is to set the clicker to a specific number, hang weight off the end of the wrench, and see where it clicks. For this setup, we used common exercise dumbbell weights to come up with the 20 pounds we needed. This includes three five pound weights plus a five pound handle assembly. The math works out like this:

- Weight X Handle Distance:

20 pounds of weight X 15 inches of handle length = 300 inch-pounds - Convert Inch Pounds To Foot Pounds:

- 300 inch pounds / 12 (inches) = 25 foot-pounds

With the above dimensions, set the torque wrench to click at 25 foot pounds.

Secure the weight to the torque wrench handle at the measured 15 inch mark with a piece of rope (lightweight nylon rope was used in our demo). Be sure the weight doesn’t touch the ground once hung.

Check to see if the wrench clicks. If it does, you’re good to go.

If it doesn’t click, it is possible to adjust the setting externally (often by way of a set screw) on some torque wrenches. Simply turn the set screw clockwise. Typically, this tightens the internal spring in the torque wrench.

To make the adjustment, take the weight off, and then repeat the process by adding the known weight to see if the wrench clicks. Keep repeating the process (adjusting the tension on the spring) by lifting the weight off the torque wrench handle and lowering the weight again. Turn the set screw and check to see if it clicks.

Calculating Your Torque Wrench Correction Factor

If your wrench cannot be adjusted (or you don’t want to mess with it) you can still figure out a correction factor.

Move the weight in one inch increments up the handle (closer to handle end). The idea is to determine where the wrench clicks using the same, known weight. If, for example, the wrench clicks at 16 inches (and it is set for 25 foot-pounds), the math for correction works out like this:

- 20 pounds of weight X 16-inches of handle length = 320 inch-pounds

- 300 inch-pounds / 12 (inches) = 26.66 foot-pounds

- The calibration works out to 25 divided by 26.66 = 0.937

Or you can simply use the length markings you made on the handle to come up with the correction factor:

- 15 inches divided by 16 inches = 0.937

When you use the wrench, multiply the wrench torque reading by the calibration figure. For example, with the above correction factor, the wrench will click at 25 foot-pounds, but the true reading is 25 X 0.937 = 23.425 foot-pounds.

If you’re not comfortable with using the calibration factor every time you use the wrench, then you can send it out to be re-calibrated.

Check out the pics below for a closer look.

What you are needing here is a known standard, you don’t have one. The assumption that lifting weights are accurate is folly. You can always weigh the “known weight” but not many folks have an accurate scale, substituting one unknown for another. Chances are the torque wrench is a better standard.

Your measurement example should be from the center of the square drive to the center point of the handle. You show the edge of the square

All your test proves is that the wrench clicks at torque values up to and including 25 when tested with 25 pound weights. How did you determine that the same setup would not have clicked at 26, 27, 30 and up? You never established the value the torque wrench clicks at with your weight

Center of the grip, not the “handle”. The handle is the whole length.

Why be pedantic when the context AND pictures make clear what the author means?

The weight of the Torque wrench handle should also be accounted for!!! Not just the 5 lb dumbell handle. The weight of the whole Torque wrench (minus half the ratchet head weight, if applicable) x total length of handle from center of drive. Also, the string should start shy of the (15″) mark and get a couple calculations for each inch either side of 15, then you can make sure it clicks at 15″ and not ahead or behind it. Or turn the Ratchet drive square downwards and use a luggage scale to pull sideways on the wrench, then no need to account for Torque wrench weight. Or same process and use pulleys to redirect the pull downwards and hang your dumbell off it again. All add complexity and room for error but you’re just checking for peace of mind. Hopefully not using it for critical Torque or to prove you didn’t damage it after a drop/ used tool purchase, etc.

Like this… makes more sense and reduces/accounts for all variables..

1,3 fTLBS one waor the other is CLOSE ENOUGH people.

In the tool room we had a mounted torque tester we were required to use on

check out. Then watch guys jerk torque to final in one step. if u said anything

answer was, been here longer you, don,t make waves or profanity filled reply…

Must be smarter than the tools your using, as dad use to say. if it says 90lbs.

I want 90 lbs.. the price of quality head gaskets demand it.

You should show this while showing it on YouTube, .

If the wrench clicks with a specific weight, you are not necessarily “good to go” – it might have clicked with a lot less. Better use a bucket with water instead of exercise weights – you can add water to it more gradually, in smaller steps – but be sure to account for the weight of the bucket and rope, and as somebody else mentioned, the weight of the handle itself (which could in fact be unevenly spread over the length of the handle)

Thank for your web site I found it very good thank you sir

Wouldn’t it be simpler to place the weight 12″ down the handle? That way, I’m measuring pound-feet and don’t need to do a conversion