What does the Dodge Magnum 360 have in common with the GM LS engine family? In fact, what does a Magnum 360 (or smaller 5.2L 318) have in common with most every production small block?

The answer is that it responds very well to a cam upgrade.

The reason for this is not some magic inherent in the fuel-injected, Magnum engine design, but rather the use of such mild cam timing on factory applications. Since power production is but one of the many design criteria of a factory cam, engineers are not free reign to add a few extra horsepower just for good measure. Believe me, they know these motors much better than the aftermarket, and could easily up the power ante if given the opportunity, but the cam choice must not only make the desired power, but also produce the desired idle quality, fuel mileage, emissions, and drivability, to say nothing of traveling 100K, 200K, or even 300K (or more) miles without complaint.

Toss in the fact that motors like the Magnum offered plenty of displacement (more than Ford or Chevy), ample head flow (for the time), and even a decent induction system (Kegger!), and you have motor basically begging for a cam swap. The question now, how much does a mild cam upgrade actually improve a 360 Magnum?

Dodge Magnum Engine Initial Testing

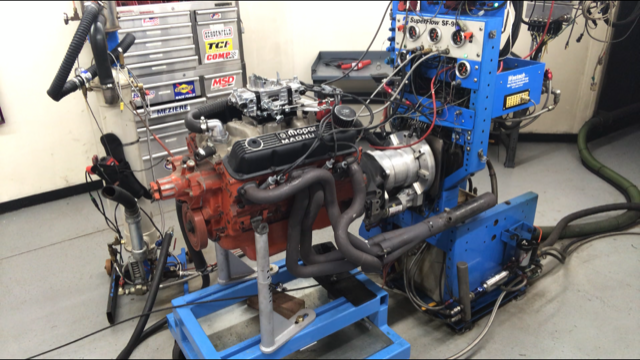

To answer this question, I took Westech Performance up on an offer to use their Dodge 360 Magnum crate motor from Mopar Performance. Having sat idle for over 12 years, it was time the old 360 got some love. Though a crate motor, the 300-hp Mopar Performance 360 was basically a production (assembly line) Magnum equipped with a dual-plane (Mopar Performance) M1 intake. It was up to the user to supply the necessary carburetor, distributor, and exhaust.

Recent testing comparing this crate motor to a junkyard 360 Magnum produced (not surprisingly) identical power results between the two (when identically equipped).

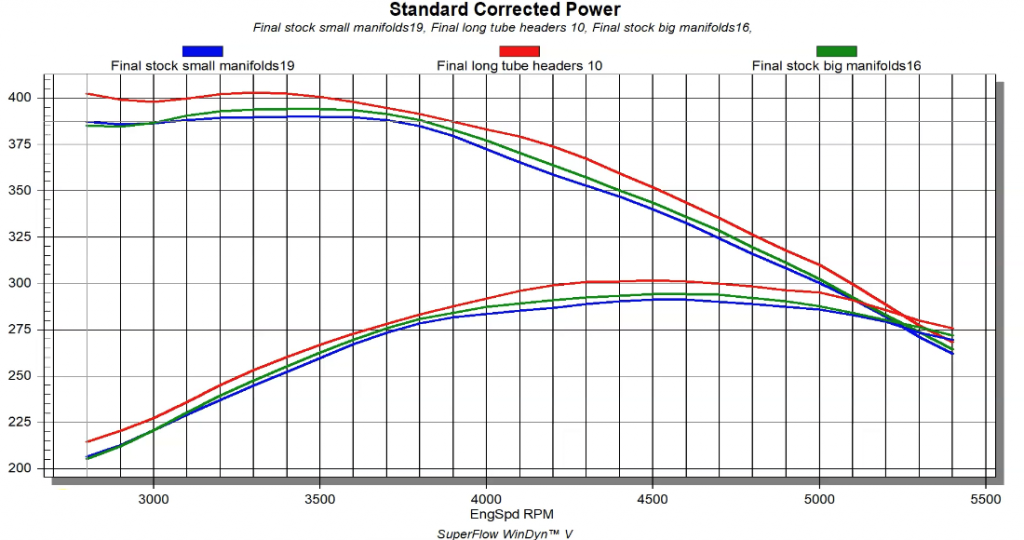

For this test, the 360 Magnum was equipped with the MI dual-plane intake, a Quick Fuel 750 Brawler carburetor and (to get things started) a set of factory cast-iron exhaust manifolds. Before the cam upgrade, we wanted to test an internet theory that the larger-diameter outlets (and internal configuration) on the 1992 and 1993 factory manifolds offered a power gain over the smaller, later (1994+) manifolds. We then compared the two different factory manifolds to a set of long-tube headers.

Equipped with the smaller (1994+) stock manifolds, the 360 produced 291 hp and 390 lb.-ft. of torque. The larger manifolds added a couple of horsepower, with peaks of 294 hp and 394 lb.-ft. of torque.

The long tube headers offered the most power on the carbureted 360, with peaks of 301 hp and 403 lb.-ft. of torque. We suspect the differences would be even greater on a wilder combination, but obviously long tube headers offered the greatest gains, even on a near-stock Magnum.

Dodge Magnum Camshaft Selection

After the exhaust modifications, we turned our attention to the cam swap. Selecting a cam for any application is very important, as the cam determines the personality of the motor. The cam must also be matched to the remainder of the components, as they must be designed to work together in the desired rpm range. No sense in selecting a cam designed to make peak power at 7,000 rpm if the intake and head flow all limited power production to 5,500 rpm.

The same can be said for intended usage. The cam designed to enhance low-speed torque, or at least not lose low speed torque in the quest for some additional power through the rest of the rev range, will certainly be different than a cam designed for frequent trips to the strip!

The cam choice must also consider things like desired idle quality, fuel mileage, and choice of torque converter (as in, is a tighter converter necessary)?

Care must also be taken with valve springs, as most cam upgrades require a matching valve spring upgrade. The springs must not only allow the desired cam lift (with concern to coil bind and retainer to seal clearance), but also sufficient spring rate to allow for the extended rpm offered by the cam. Lucky for enthusiasts, the cam manufacturers often have spring recommendations to go with their cams. When it comes to camming your Ram, choose wisely!

Dyno Testing the Dodge Magnum Cam Swap

Knowing all of this, we selected a suitable cam for the 360 Magnum. With low-speed torque and a daily driver in mind, we chose a mild, but plenty powerful grind from Comp Cams.

Designed for computer-controller Magnum engines, the Xtreme Energy XR262HR cam offered .480 lift, a 212/218-degree duration split and a 114 degree LSA. The wide LSA ensured a friendly idle quality, while the added lift and duration all but guaranteed additional power. Comp offered milder and wilder grinds for looking for even more drivability or power.

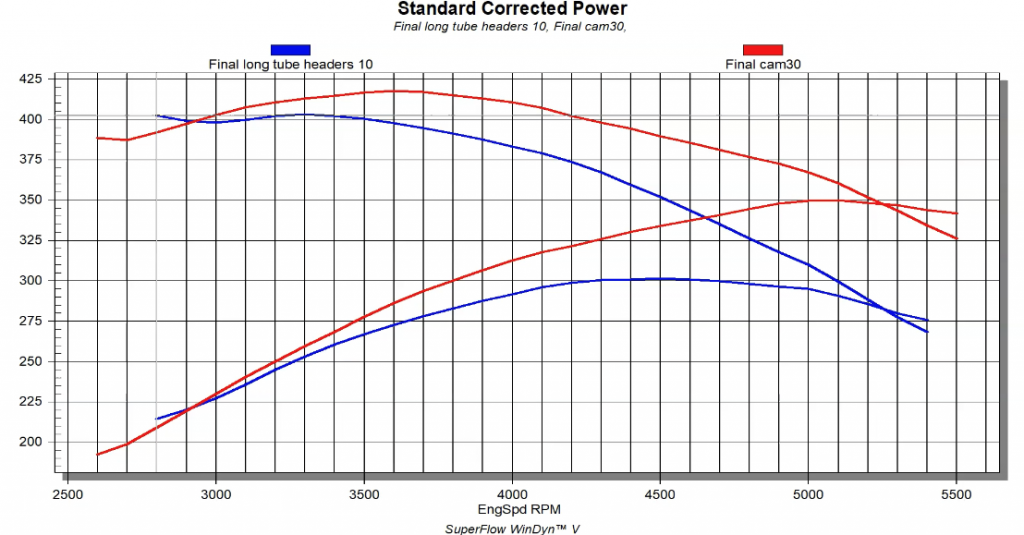

We made short work of the cam swap, reusing the factory lifters. As luck would have it, sometime in the life of this crate motor (did we mention it had been sitting idle for about 13 years?), the springs had been upgraded. They offered not only 140 pound of seat pressure, but sufficient coil bind clearance for our .480 lift. Run with the stock cam and headers, the Magnum produced 301 hp and 403 lb.-ft. of torque.

After installation of the new Comp XR262HR cam, the peak numbers jumped to 350 hp (technically 349.8 hp) and 418 lb.-ft. of torque. The cam swap not only improved both peak horsepower (by 49 hp) and peak torque (by 15 lb.-ft.), but the cam offered power gains from 3,000 rpm on up. In truth, we step up a little more than we wanted on this Magnum application.

In typical go-for-the-glory fashion, we were more enticed by the big peak horsepower numbers than the usable power down low. For a daily driver, an even better choice might be the XR258HR which drops down 6 degrees of duration on both intake and exhaust, but it might be nice to see how close we can get to 400 hp with a few more mods like hand-ported and milled heads and a different intake manifold.

Hello. I can relate very much to what you did to this engine. My 1971 truck engine 360 was bored out .060 to 371 cid. Has mildly ported cast iron heads, 202 intake valves, adjustable rockers, holly 750 com carb. Dual plane intake and a complete cam 471 lift extreme energy cam. I figured around 330hp. Engines are comparable except you have magnum heads. It’s in a 1970 hemi orange charger. Won a few trophy’s with the car. Thanks for being a Mopar fan like I am. Bruce

Se puede poner esa leva en un motor 5.2 magnum con inyeccion electronica computadora reprogramada Dodge ram año 1997

Just picked up a Dodge Ram with the Magnum engine. Looks like headers and a cam swap are in the plan for upgrades this year. Thanks for the info, Sir RIchard.

is this cam a magnum part # or a # for a magnum with the LA front timing cover?? I have a 2003 Durango RT that I want to upgrade cam slightly along with the Mopar 4 hole manifold kit. I put a magnum engine in a 1980 Mirada using the fuel pump adapter & LA OE timing cover & front drive assemblies.

Can u use this cam with factory FI that comes on the 5.9..360 motor

Does this cam stop it from passing smog check

can i use a cam with 480.lift and a 212 218 duration with a 1998 factory fuel injection that comes on the 5.9 360 if i up grade valve springs as well

The EFI magnum likes a 114-115 LSA. Anything less and idles and drives the ECM knutts. Also, you won’t need anything bigger than 20lb or the OEM injectors. The ECM can’t manage huge injectors, potential cyl wash and the stock injectors can get over 500hp! Dave at B&G does magic with initial and final tunes. Make sure to contact John at Southeastperformance.net for all the parts or anything that might get you to better power. John doesn’t sell parts. He works with you, your budget and goals. I don’t and won’t go anywhere else. Good luck.

There was a Dodge 360 engine with 360 HP, in reality I am looking for the aspects of that camshaft to order to manufacture one with better Lift and a little more DURATION, do you have that information? thank you

What pushrods do you use with that xr262hr

cam in the 5.9 magnum?

This is great stuff, I have been a MOPAR fan since as far as I can remember, had a 70 Duster I put a (Id guess a late 60’s 383 HP engine in back in 85 and WOW I wish I had that now. I digress. I have a 2000 Durango 5.9 Magnum and I want to give it a decent upgrade, Is it possible to use the Stock EFI (If needed upgrade injectors) With the Stock ECU as well as run Dual exhaust and if so can you recommend any links or ?? I can go check out to see what is needed to get this project to all function properly together

Another fine article by Richard Holdener who has unlimited knowledge of engines off the top of his head, he’s just done so many combinations and instead of listening to the exhaust to determine the power output, he uses a Dyno so he knows exactly what is going on. I’d love to be able to send him an engine for him to tune.

For those Interested in more by Richard, check out his videos on YouTube.