What the heck is an L99? We know GM uses these alphanumeric designations to label its many engine configurations, some of which were more notable than others. For instance, most Chevy fans recognize the famous ones, like DZ302, L88, or LS6—and some of the real diehards even know the difference between the LT-1 and LT1 (first and second gen performance 350 motors).

But who here knows about the L99?

Note: We’re NOT talking about the LS-based L99 here either.

What is the “Baby LT1” Chevy L99 Engine?

Not quite as legendary as its larger brethren, the L99 was actually a diminutive 4.3L V8.

What? A 4.3L V8? Don’t you mean the 4.3L V6?

Nope, the L99 was a gen-2, LT1-based 4.3L V8 offered in the (of all things) full-size Caprice Classic!

Why did GM use the smallest small block in one of the largest passenger vehicles? More importantly, why did GM use the torque-lacking, short-runner, LT1 intake on the smallest V8 ever offered in the biggest package?

What the little V8 needed more than anything was additional torque. And adding torque to the little 4.3L is what this test is all about!

Swapping Intakes to Make More Torque

The most obvious answer to adding torque was with displacement, and GM did exactly that by offering a larger, more powerful 5.7L version of the LT1.

But what about the 4.3L folks? Besides, we have always wanted to compare the previous generation, long-runner, LB9/L98 Tune Port intake to the later, short-runner LT1 intake, and this was a perfect opportunity.

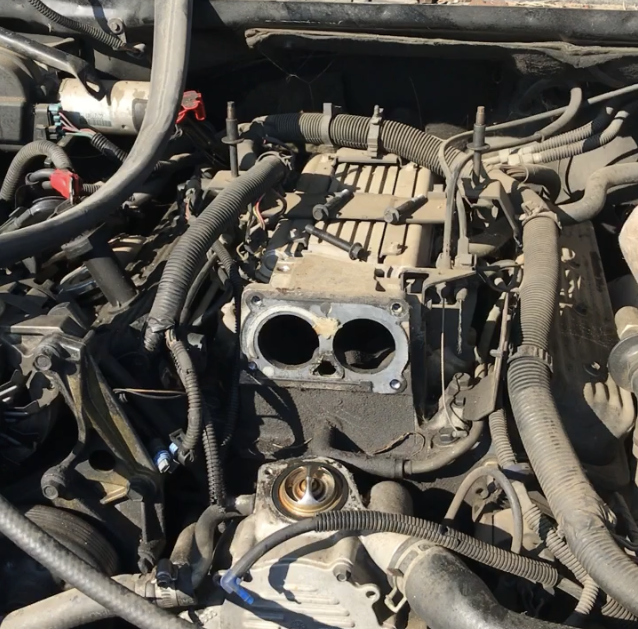

The big hurdle for this test was the fact that the Gen-2 LT1 intake and heads featured a different bolt pattern than the previous (conventional) SBC intakes. The Gen-2 LT1 featured reverse cooling, meaning (among other things), dedicated head casting with different intake bolt patterns and no coolant passages in the intake. The lack of water flow through the intake presented no problem for the intake swap, but the bolt-hole alignment required attention.

Lucky for us, Jim Hall and the boys over at Tune Port Injection Specialties (TPIS) welded, milled, and drilled on the LB9/L98 lower intake until the holes matched the bolt pattern on the LT1 heads. It was necessary to stuff rags or paper towels into the water passages to stop oil from the lifter valley from finding its way out (the LT1 gaskets don’t cover the water passage opening on the L98 intake), but this was an easy fix.

Our L99 Test Engine

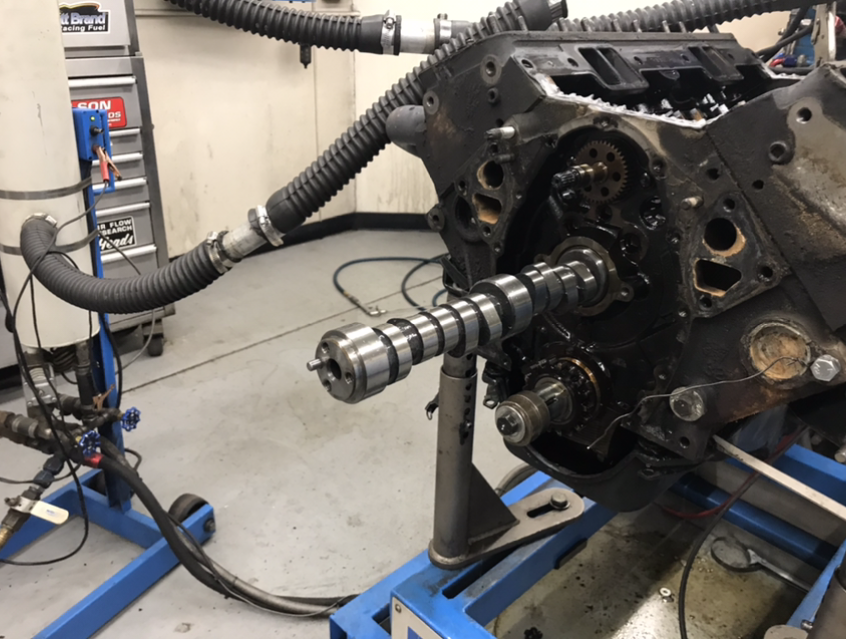

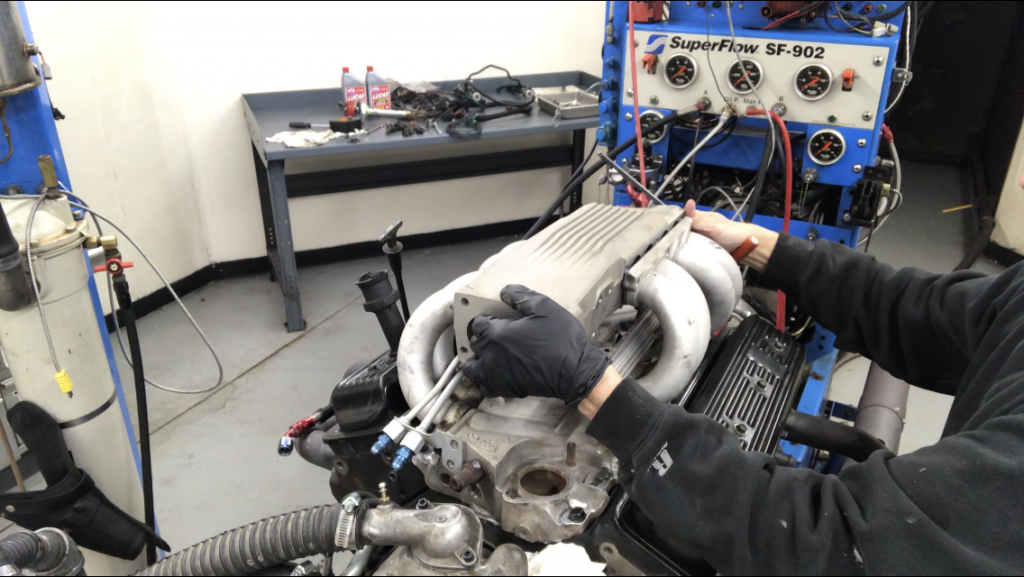

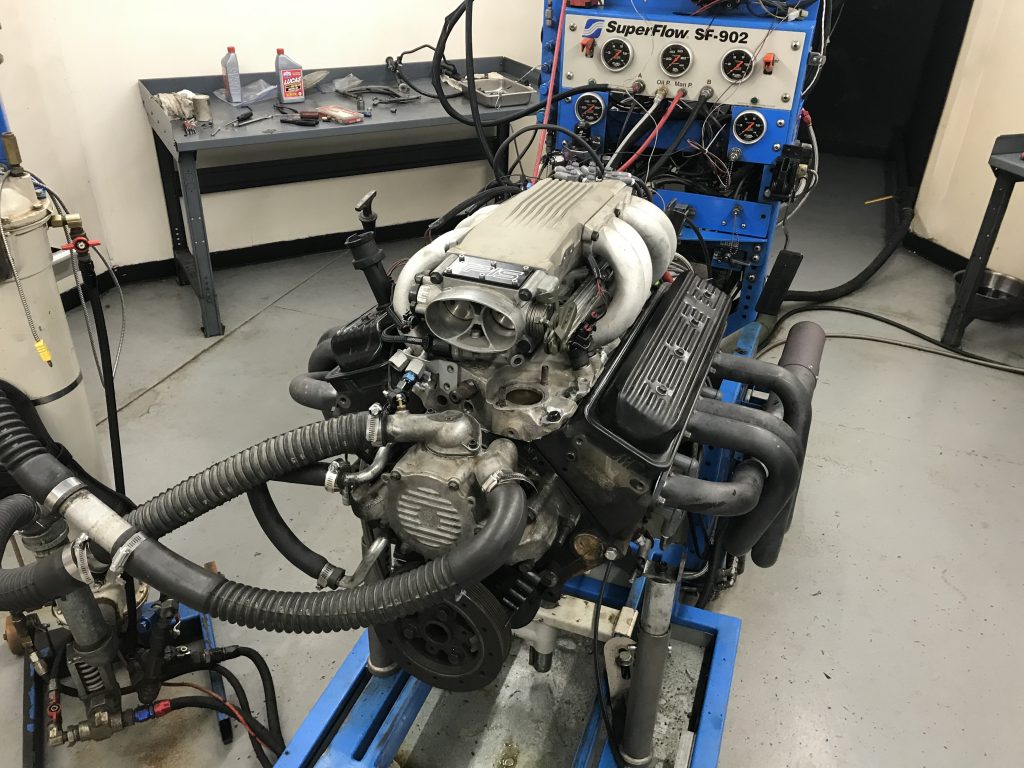

With the TPI intake now swap ready, we installed our modified (junkyard) L99 up on the dyno. Prior to running, the factory LT1 was modified as well, by drilling a hole in the back to accept a conventional distributor.

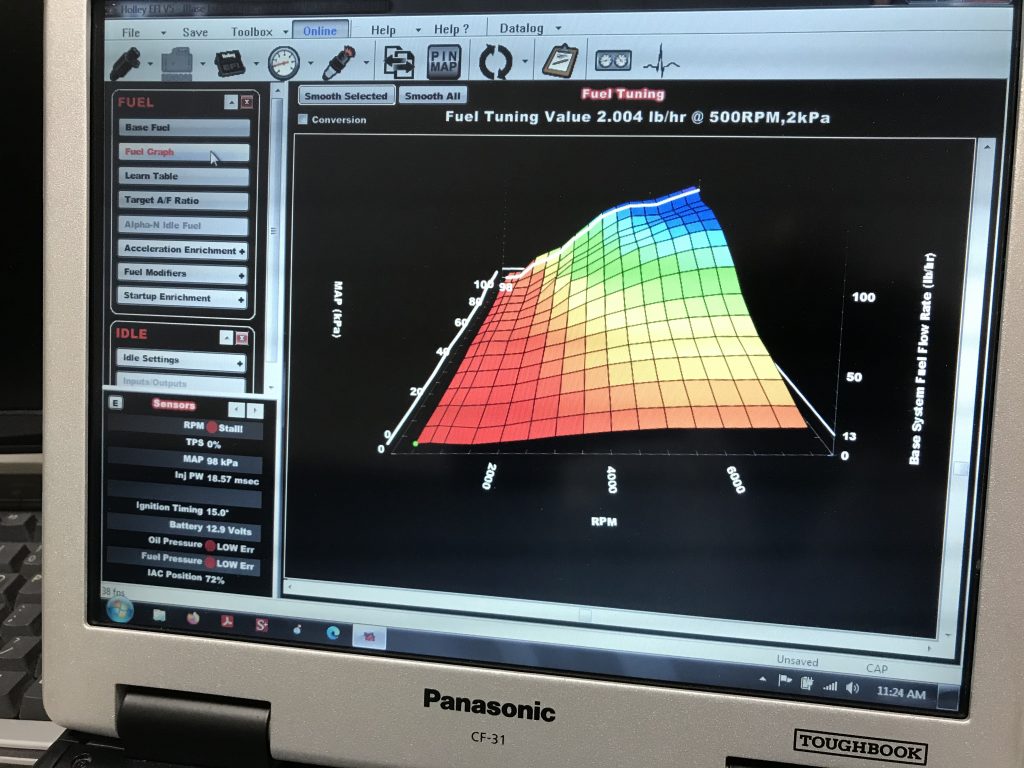

Unfortunately, the Holley HP ECU would not accept the trigger pattern offered by the factory OptiSpark, so we pushed the easy button and took out the hole saw! After drilling and tapping a hole for the distributor hold down, we were in business.

The little L99 had been previously modified (lots of testing) with a mild cam (.410″/.427″ lift, 207°/214° duration, 117° LSA), a valve spring upgrade, and a set of Comp 1.6-ratio (guided) roller rockers.

The 5.7L LT1 was offered with both iron and aluminum heads, depending on the application, but the smaller L99 received dedicated (small-chamber and valves) iron heads. The iron heads used on the LT1 featured both larger valves, larger combustion chambers and increased flow. The iron LT1 heads are said to be on par, or even slightly better than, the aluminum LT1 heads used on the F-body and Corvette applications. The smaller L99 heads were down on flow by 10 to 15 cfm (depending on valve lift), but the smaller chambers (49cc vs. 57 to 58cc) meant a head swap might not yield the desired power results.

Testing the L99 Intakes

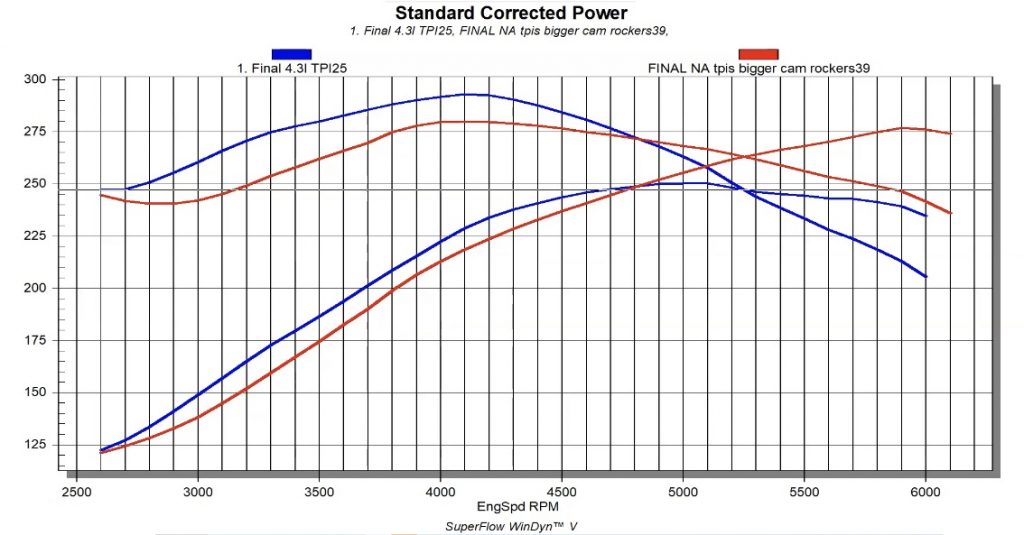

The 4.3L L99 was first run with the stock LT1 intake, stock throttle body and 1-3/4 inch long-tube headers. Smaller 1-5/8 inch headers were run in a later test and improved the power and torque by five to six horsepower and a like amount of torque through the whole curve. After optimizing the AF and timing curves (30 degrees total), the LT1 intake offered peak numbers of 277 hp at 5,900 rpm and 279 lb.-ft. of torque at 4,100 rpm.

After installation of the LB9/L98 Tune Port Injection intake, the peak power dropped to 252 hp (at 5,000 rpm), but peak torque jumped to 293 lb-ft at 4,100 rpm.

True to form, the TPI system improved torque production up to 4,800 rpm, but the short-runner LT1 intake offered improve top-end out to 6,000 rpm. The question (as always) becomes, where do you want your power production?

The ideal situation would be to have both, but short of a dual-runner intake, that would be a difficult task, unless you just stepped up to the larger 5.7L. Of course, you could always combine the 4.3L crank and rods with the pistons and block from the 5.7L LT1, and make yourself a (de-stroked) Gen-2 DZ302. The other option is to combine the crank and rods from the 5.7L LT1 with the pistons and block from the 4.3L to produce a 305 (stroker 4.3L).

So much cool testing to do, but for now, know long runners do add torque, but the penalty is almost always peak power!

what is the best power adder for a new 92 5.7 tbi motor is there a different tbi and intake for this motor thank you Brian

Vortec heads and intake needed for that and an external EGR source. Only chip ever made for that application was made by Edelbrock, they stopped making them but might have some on the old shelf. That would really wake your engine up. And there is always the aftermarket chips or custom.

I’m interested in doing a 4.3 l conversion for Suzuki Samurai and like the idea of a V8. Would you know, it would fit in like a V6

No…..the GM 4.3L V6 is a smaller engine block than the 4.3L V8.

Interesting article you always are entertaining and precise.

I like the idea of the l99 motor for a different reason than anyone else. I have seen so many bustle back cadillacs get scrapped becuase the 4.1 died or the cam was wiped.

The l99 is almost the same size motor 4.1 to 4.3. Why not use a dual plane motor and keep the TBi? I know there are other engines of a similar size: 267 sbc, 260 olds, 307 olds etc, 4.1 v6 buick, small block buick motors.

These motors might be easier to swap in, but they, in my opinion, are not as good a candidate, while maintaining the original fuel delivery system.

Back in the 80’s people would go to the junkyard to find a tbi throttle body off of a cadillac with the 368 big block. They would swap the injectors from the 4.1 TB to the 368 throttle body. The result was, guessing, 20hp or 25hp. The same thing could be done to a tbi conversion on an l99.

Further more, the throttle body could also be opened up to make more power.

What is there too lose? Your Bustle back, with failing motor that could have be resurrected with an l99.

I meant dual plane intake with tbi adapter plate in order to keep the 4.1 v8’s fuel delivery system.

what camshaft did you use to upgrade l99 engine? cannot find any by your description

Vlad, those cam specs look like a stock L98 cam from a 89-91 vette or F-body. The Melling CCS-40 with 1.6 rockers is the closest you can get without spending a ton and is about the perfect upgrade also for a stock roller 305 or either of the vortec 305/350 engines without doing valve springs.

Hay! I really loved this. I am in the middle of building a full roller GM 302, got a crankshaft and rods out of 4.3 l V8. Found a new 5.7 block that the crankshaft will work in both have one pice rear main seals. Need to know before i start ordering parts ie camshaft what the crankshaft will do as far as building HP and Torque. thank you

also interested in building a 302 from a Vortec 5.7 block. hows the project going ?

Nice job! Can you maybe help me with some simple questions i have for my L99 rebuild?