The great thing about being an LS enthusiast is you don’t have to worry yourself with the petty problems that plagued the lesser Gen. I small blocks, right? Case in point, intake manifolds.

The O.G. small block guys will bicker endlessly about whether to top their carbureted small block with a single plane intake manifold or dual-plane intake. Since the LS came factory equipped not only with electronic fuel injection, but impressively powerful (factory) intake manifolds, why on earth would LS owners get caught up in the single-plane v. dual-plane debate?

Well, being the darling of the industry, the reality is that a great many LS motors are not only swapped into less modern machinery, but some of those are even topped with carburetors. The combination of available intakes from trusted sources like Edelbrock, and necessary ignitions controllers from MSD made carburetors an easy, affordable alternative to running fuel injection.

What this means is that even LS owners are forced to choose between the available single- and dual-plane intakes.

Much like their Gen. I counterparts, LS owners need to look at much more than just power numbers, especially peak power numbers, when it comes to choosing the right intake manifold. While the power and performance are certainly important aspects, there is a great deal more that goes into the ideal intake choice, including things like engine combination, application (street or race) and, last but not least, displacement.

While we all like to think we live and breathe nothing but performance, the reality is that the vast majority of us spend most of our time at significantly less than full throttle. This is especially the case for daily drivers, but even on an all-out race motor, things other than peak power and/or peak torque should be considered.

And it starts with engine combination.

Your engine combo will certainly help determine the intake choice as a stock, or near stock motor, will most likely run much better with a dual plane than a single plane. The opposite is true, if you are putting together a wild, high-rpm combo, which might be better suited to the racy single plane.

Obviously, your combination should go hand-in-hand with the application. A stock or mild build, for example, would be best for a daily driver, while a race application would be better served with wilder cam timing, extra head flow, and a high-rpm intake (meaning single plane).

The final element is often overlooked, possibly even more so on an LS application. We all know the LS family makes considerable power, and people often associate this power potential with the need for MORE intake manifold. Much like carburetion, the trend is to over-intake a smaller motor. The key is to remember that a single plane and dual plane are not only designed for different effective engine speeds, but this effective rpm range can change with displacement. What might work well on a larger 6.0L or 6.2L LS, can be less than optimal on the “Little Man” (4.8L).

To illustrate the difference between single- and dual-plane intakes on the Little Man, we set up a test to compare them on a typical (mild-cammed) 4.8L. Just for grins, we tossed in the factory 4.8L truck intake to demonstrate what the carbureted guys might be giving up by not running modern injection.

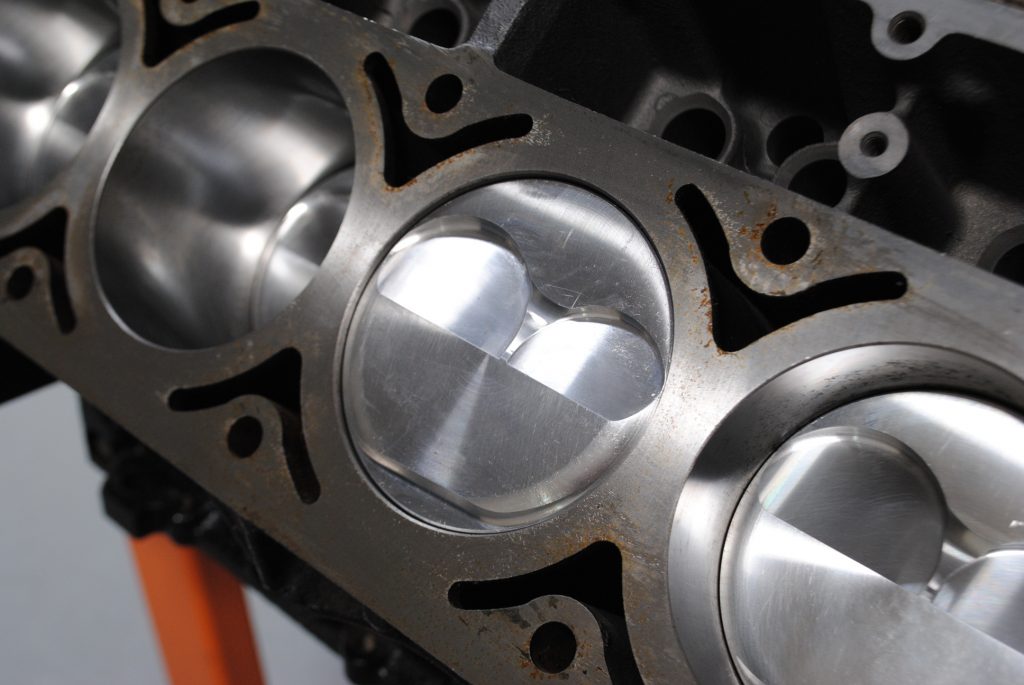

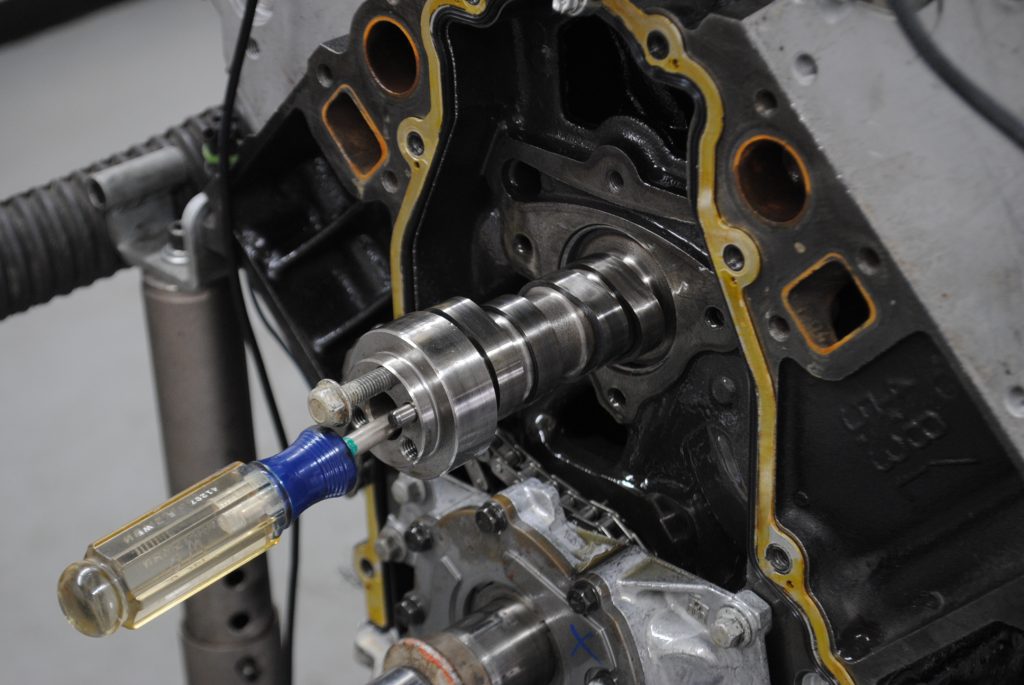

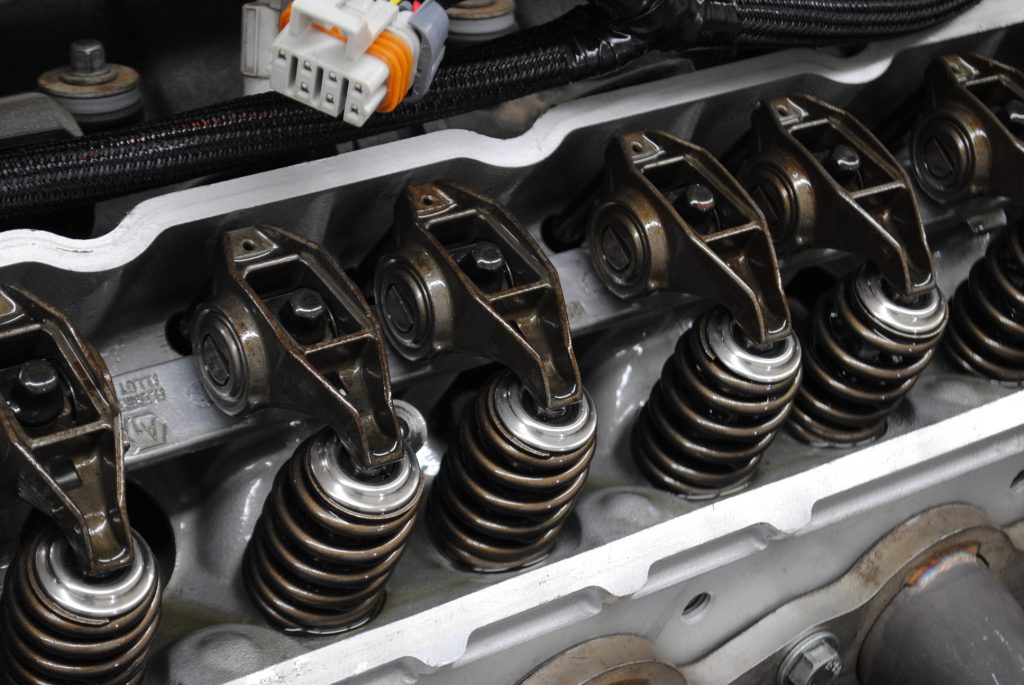

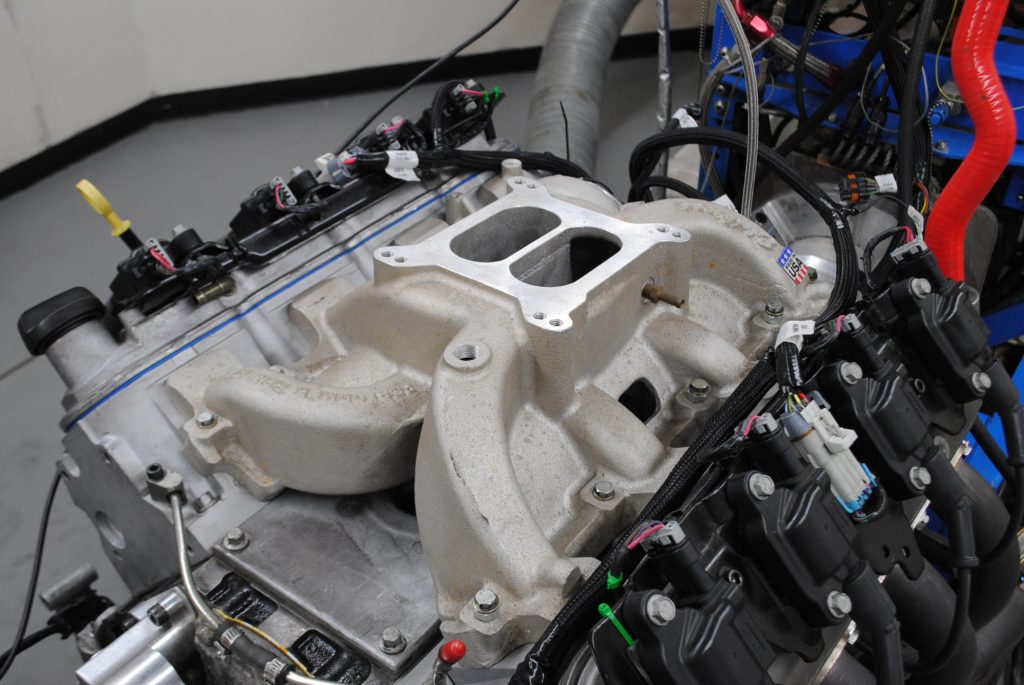

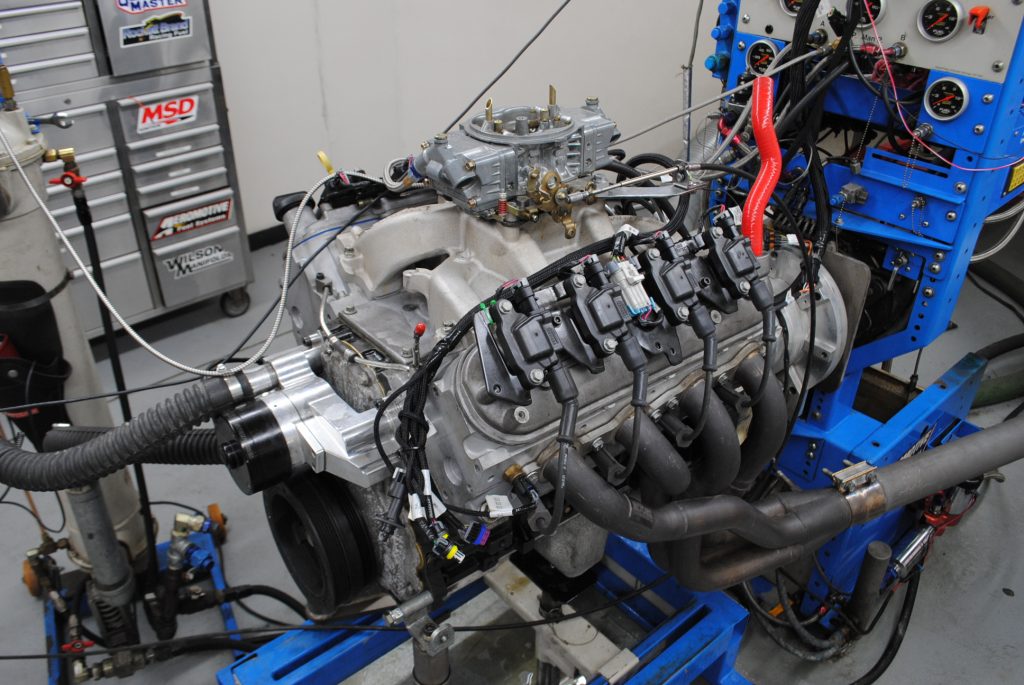

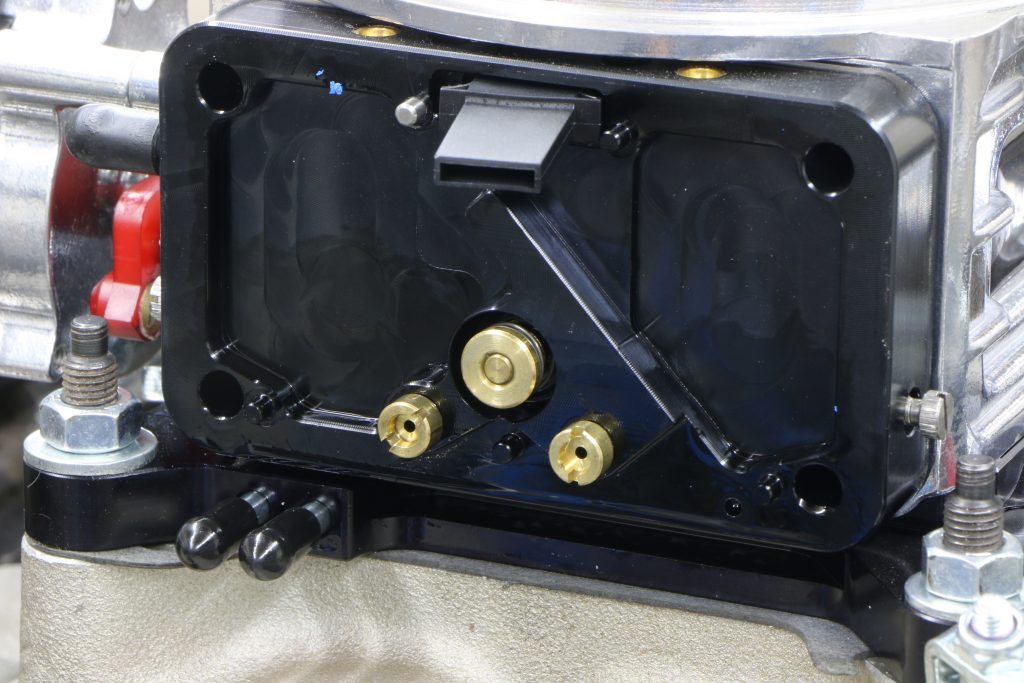

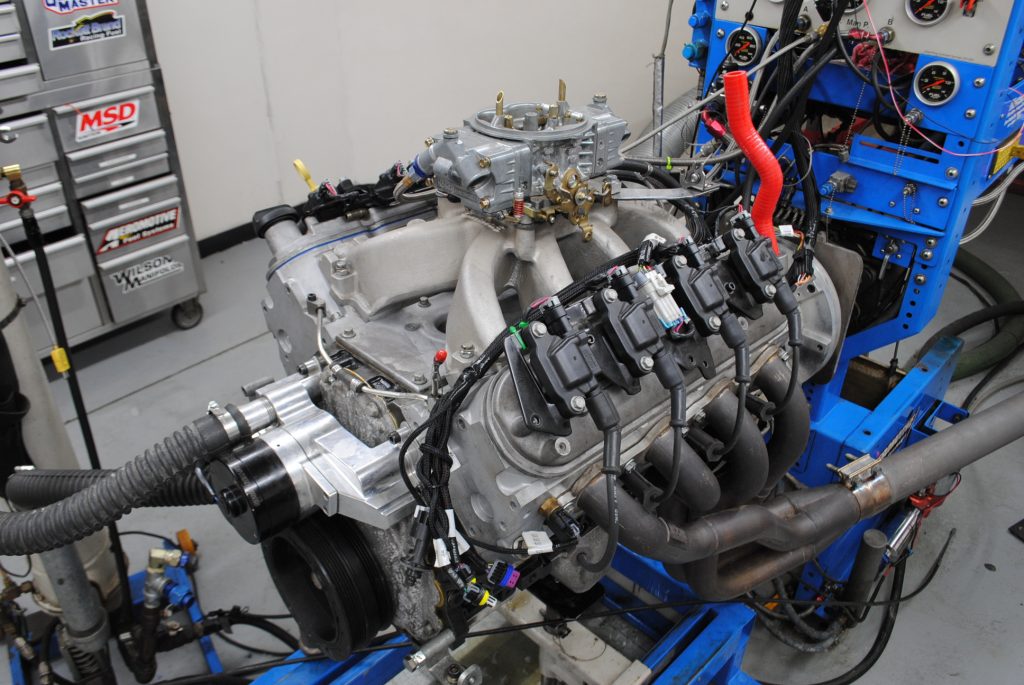

To get things started, we set up a junkyard 4.8L (with forged JE pistons) with a few quick mods, including a mild cam and springs before testing each of the intakes. The 4.8L was also equipped with long-tube headers, an MSD ignition controller (to set the timing curve) and a Holley 650 carburetor. Naturally, each carbureted intake was tested under the same conditions, meaning the same A/F and timing and temperatures. For our mild cam, we chose a Comp XR265HR that offered a .522/.529-inch lift, a 212/218-degree duration split and 114-degree LSA.

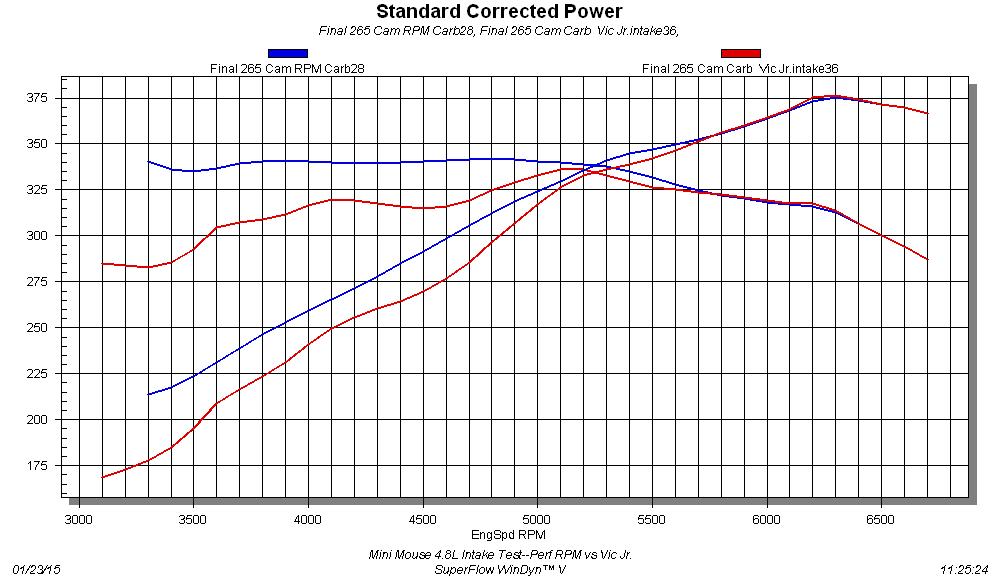

First up was the dual-plane Edelbrock Performer RPM. After jetting, the dual-plane allowed the 4.8L to produce 375 horsepower (at 6,300 rpm) and 342 ft.-lbs. of torque (at 4,800 rpm). Check out the graph below for an idea what the entire power curve looked like, as this was much more important than the peaks.

After swapping over to the single-plan, Edelbrock Victor Jr., the peak numbers changed to 376 horsepower (at 6,300 rpm) and 336 ft.-lbs. of torque (at 5,100 rpm), Though the peaks were similar, the curves couldn’t be more different. Check out the fact that the dual plane offered not only every bit as much peak power as the single plane, but offered substantially more torque production (over 55 ft.-lbs. at 3,000 rpm!). Given the fact that the Little Man 4.8L was never known for torque production, such a loss should not be welcome (or even tolerated)!

For the smaller 4.8L, the dual plane is definitely the hot set up.

In the comparison between the single- and dual-plane intakes on the 4.8L, the dual plane definitely came out on top, but where does that leave the factory truck intake? Were we to line up the truck intake, it would be most closely comparable to the dual plane, as both share a propensity for torque production. The long-runner truck intake was definitely designed to enhance average power production, though the long, equal-length runners are not shared by either the single- or dual plane-designs.

To illustrate the differences in the power curve offered by the truck intake, we ran it on our Little Man 4.8L. Run with the EFI intake, the mild-cammed 4.8L produced not only more peak power than either carbureted combo (382 horsepower at 6,100), but also more peak torque (359 ft.-lbs. at 5,100 rpm). Compared to the single-plane intake, the truck offered more power through the entire rev range, but the low-speed torque champ was actually the dual-plane Performer RPM. It looks like the single-plane/dual-plane argument is pretty well settled on the mild 4.8L, but what about the choice between the dual plane and the truck intake?

Even on the Little Man LS, the intake debate rages on!

[…] The great thing about being an LS enthusiast is you don’t have to worry yourself with the petty problems that plagued the lesser Gen. I small blocks, right? Case in […] Read full article at http://www.onallcylinders.com […]

Do you have a graph to show the power curve off the stock manifold compared to the aftermarket? Thanks.

Look up Richard Holdener on YouTube. He has dozens of videos during his test runs and that curve you are looking for is on the carb vs EFI video.

I believe it was tagged Little Man intake test.

I watch his video’s several times a week. including his live Q&A sessions.