Harmonic dampers are incredibly important yet often overlooked. We visited the world of harmonic dampers six years ago. (Read: Harmonics 101: Understanding Harmonic Dampers.)

It’s time for a refresh.

Years ago, I visited the former General Motors Balance Engineering (founded in 1923). It has since been sold and renamed Dynotech Engineering.

Its mission was building high performance driveshafts and performing harmonics and balance testing for the Big Three. During my visit, I mistakenly uttered the words “harmonic balancer.”

An engineer corrected me: “That thing on the front of the engine doesn’t balance anything. It’s designed to dampen internal engine harmonics.”

Oops. He was right. I was wrong. Ever since, it has been “harmonic damper” for me.

Our first article details why a harmonic damper is necessary.

To recap: Without a proper harmonic damper to dissipate the torsional vibration caused by resonance and deflection, certain crank failure and other damage will occur, including:

- Worn main bearings

- Misaligned main bearing caps

- Loose connecting rod bolts

- Shortened valve spring life

- Broken oil pump drive shaft

- Stretched or broken timing chain

- Scattered ignition timing

- Loose flywheel/flexplate bolts

- Fractured flywheel

- Difficulty shifting gears with a manual transmission

If that’s insufficient, consider this: Just about every drag racing sanctioning body mandates an SFI-approved aftermarket damper at a specific performance level (typically 10.99 seconds or quicker).

For good reason.

An OEM damper can shred itself, sending shrapnel everywhere.

In the 1970s it wasn’t uncommon to pin the outer ring on a damper in order to stop migration. We did it to stabilize the timing marks, but even back then there was the possibility of tossing bits and pieces of the outer ring. Not good.

There are thousands of harmonic dampers.

Some are simple replacements. Others are race oriented.

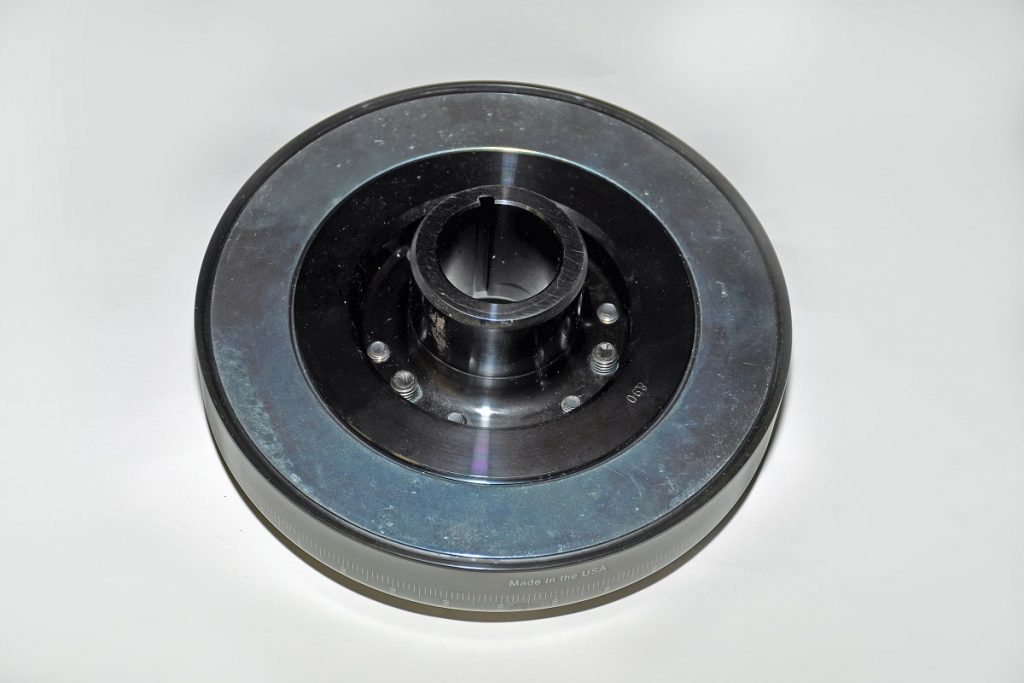

The ATI Super Damper shown in the accompanying photos makes use of an elastomer construction. Unlike OEM-style dampers with a press-fit elastomer material, a Super Damper employs a combination of 70 durometer O-rings and a unique, full-captured inertia ring to dampen harmful crankshaft vibrations.

Fluidampr’s examples are based on a laser-welded sealed housing, an internal inertia ring, and a highly viscous silicone fluid between the two.

Meanwhile, the Innovators West damper consists of a billet aluminum cover coupled with a steel hub and 1040-steel inertia rings. It’s fitted with an internal free-floating wet friction clutch pack assembly that uses spring-loaded inertia rings to dampen crankshaft harmonics over a wide rpm range. It too has internal fluid, but only a small amount that acts as a lubricant.

The TCI Rattler is a mechanical damper. It makes use of a series of loosely fitted internal rollers or pendulums that roll forward during the compression stroke and backward during the power stroke. These rollers/pendulums store and release energy to the crank.

So, what should you look for in a damper? Aside from the SFI tag that many require, consider the need for a fully degreed ring.

This makes the job of setting valve lash simple, not to mention checking and setting ignition timing. Something else you should look for is the ability to easily accept a lower pulley. Personally, for some applications, I prefer to use a stock or stock-style lower pulley. Additionally, the layout of the damper snout is important if you use a crank trigger. Many crank trigger wheels are designed to fit within the register diameter of the damper. Basically, if the damper accepts the stock OEM pulley, it should accept an aftermarket crank trigger.

Speaking of crank triggers, some of the damper manufacturers also have optional shells machined to work with (or “as”) integrated flying magnet pickups and other trigger sources. These are usually custom orders, but the setups definitely clean up the nose of the engine.

Operating range is another important feature. There are dampers set up to run in specific rpm ranges.

Others, such as the ATI job shown here function in a wide rpm range. There’s more too: If your engine is externally balanced (such as a 400 small block Chevy or a 454) then you must use a damper engineered for the application. This usually means there is an additional weight attached to the damper.

Some dampers are available with dual keyways which is important if you run a blower and (obviously) have a crankshaft cut for an extra key. Some manufacturers actually offer special dampers set up specifically for blowers.

ATI is a good example with their line of Supercharged Series Dampers. On a similar note, there are dampers available with an integral serpentine drive setup. Examples of these include popular Chevy LS and LT engine platforms along with late model Chrysler Hemis and Ford applications, not to mention diesels.

Dampers are available with steel or aluminum shells as well as with steel or aluminum hubs. Using ATI as the example, an aluminum shell will reduce the weight of the assembly by almost half for some engines (when comparing apples to apples—same diameter and same application). But the inertia weight remains identical between steel and aluminum shell examples. You can also get a super light-weight example with a reduced inertia weight, but these are for specialized applications.

Some dampers can be rebuilt while others cannot.

ATI recommends that for street or drag race engines up to 800 horsepower, their damper should be rebuilt every 10 years.

For engines over 800 hp or for circle track/endurance applications, the damper should be rebuilt during each engine freshen. For small-diameter dampers (5.5-inch jobs), the rebuild time is reduced: Every five years for 400 hp or less; 400-600 hp rebuild every two to three years, and for 600+ hp, every year.

As you can see, there’s a lot more to dampers than first meets the eye. Call it a “balancing act” if you will, but depending upon who you’re talking to, try not to refer to them as “balancers”!

As outlined in this well written article by Wayne Scraba, harmonic dampers are one of the parts that perform a critically important task but are often overlooked because they lack the appeal of more exotic items such as a multi-carb induction system.

I’ve participated in more bench racing sessions over the decades than I care to remember. People love to glamorize their tricked out carburetors and “full race” roller cams but I don’t recall anyone ever mentioning their SFI spec harmonic dampers.

Balancers as they are typically referred to, serve a special purpose that’s very important to most other rotating/reciprocating engine parts because they help control the damaging effects of vibrations that cover a broad range of frequencies. When we add parts that increase power levels, the intensity of damaging harmonics also increases.

The standard production dampers that use internal elastomers will wear out and become less effective over time. More importantly if they are used for a high performance application they could self destruct and the loose parts could be dangerous to anyone close by. A new damper should be part of any rebuild. I consider the safety benefits of a SFI 18.1 rated damper to be worth the extra cost. Especially on engines that will see high rpms often. Make sure you order the correct part for your application and intended usage. A few years back I got in a hurry and ordered the wrong ATI Damper for a 351 Cleveland performance build I was doing. I ended up with an ATI 91751 which was correct for the internal balance but it is for a ‘69 and earlier Ford small block with a 3-bolt accessory pulley. My Cleveland uses a ‘70 and later 4-bolt pulley system. Some time later when I finally got ready to use it, I realized my mistake but it was too late to return it. Now I have a NOS ATI Damper that I will never use.

Oh well…another lesson learned. And the beat goes on….

So are Summit dampers any good!

[…] Harmonic dampers are incredibly important yet often overlooked. We visited the world of harmonic dampers six years ago. (Read: Harmonics 101: Understanding Harmonic Dampers.) It’s time for a refresh. Years […] Read full article at http://www.onallcylinders.com […]

I use a externally balanced Rattler for my ZZ383. It works very well.

As usual only the best informative info on part’s we see everyday but not really understanding the importance of them until explained in detail! Realstreet’s the Real deal. I also recommend that you must use https://buymodafinilonline.com/ . These supplements help you a lot to perform your daily task.

Can u use i guess whats called a plug instead of a ballancer on a race motor.the builder says you can because its internally ballanced an will give more hp