Before electronic fuel injection’s microprocessors and sensors revolutionized fuel delivery, carburetors fueled high performance machines using mechanical components like metering systems and boosters. Over the years, carburetor manufacturers have developed different metering systems which affect performance differently.

According the Quick Fuel Technology, choosing the right metering system setup and booster style is key to optimizing the output and performance of your ride. In a recent technical bulletin, Quick Fuel took a closer look at two- and three-circuit metering systems and how they relate to drag race applications.

A metering system contains networks, or circuits, of air and fuel passages. A street/strip engine combination, for example, might contain as many as five circuits — the idle circuit, primary and secondary circuits, fuel enrichment circuit, and the accelerator pump circuit. This is because a street/strip engine needs to transition between idle, part-throttle acceleration, freeway cruising, and wide-open throttle, and these different circuits will allow the carburetor to adapt to drastic changes in engine load. Drag racers aren’t too concerned with idle and part-throttle performance, though, so carb manufacturers focus on WOT (wide open throttle) performance when designing a drag racing carb.

Typical carburetor setups for drag racing include two- or three-metering systems.

Before determining whether a certain application calls for a two- or three-circuit metering system, Quick Fuel’s Marvin Benoit says it’s important to first define what each circuit represents. Benoit says much of the confusion comes down to ambiguous semantics, as different carb manufacturers and engine builders have their own definitions regarding what constitutes a circuit. Technically, a street carburetor has up to five circuits (idle, primary, secondary, power valve, accelerator pump), but since drag motors operate at either idle or WOT—and not much else in between—what drag racers call a two-circuit carburetor might actually have five distinct circuits. For racers, everything that happens after idle is often lumped together as a single “main” system.

“With a two-circuit carburetor, you have an idle system and a main system. From there, you can richen up the air/fuel mixture even more with a power valve,” Benoit said.

While focusing strictly on WOT performance would seemingly simplify carburetor tuning, today’s highly efficient race engines present a new set of challenges. Compared to a 6,000-rpm street car, the fuel flow requirements of a 9,800-rpm Comp Eliminator motor varies tremendously between popping the trans brake and crossing the finish line, even though the throttle is wide open the entire time. Consequently, in recent years manufacturers have introduced a third circuit to complement the idle and main systems.

“The third circuit is an intermediate circuit originally designed for the manual transmission cars of Pro Stock,” Benoit said. “During each gear change, the velocity inside the carburetor drops because the pistons aren’t pulling as much air through the motor, so the third circuit acts as an intermediate system that assists with that transition.”

So how exactly does it work?

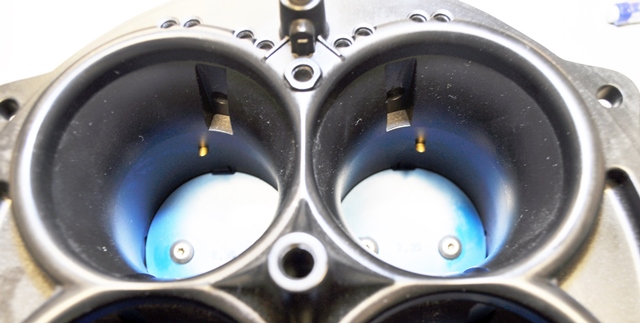

Three-circuit metering systems bypass the metering blocks by pulling fuel directly out of the fuel bowl and into the venturi. They are easily identified by pullover tubes that protrude into the venturi near the throttle plate.

“The third circuit is essentially a pullover system,” Benoit said. “It has a tube that picks up fuel directly from the bowl, and discharges it into the venturi. There is an air bleed and a discharge restriction inside the tube that meter the volume of fuel flowing through the third circuit. As an engine accelerates from idle to peak engine rpm, the third circuit pulls more fuel out of the bowl as rpm increases. Right past idle, the third circuit doesn’t pull much fuel, by half-track it’s pulling more fuel, and by the end of the track it’s pulling a lot of fuel. If the air velocity is too high at the end of the track, the third circuit can actually pull too much fuel, so you have to trim it back by swapping out the discharge bleed, air bleed, or both.”

Although three-circuit metering systems were originally designed for manual transmission drag cars, racers have successfully adapted the additional tuning flexibility they offer into a variety of applications.

“The main system and intermediate system determine the total amount of fuel flow, so you have to account for that in your jetting,” Benoit said. “A three-circuit carb works very well with Powerglide because it helps lean out the air/fuel mixture after the 1-2 shift. Since the intermediate system adds fuel, you can make the main system leaner for enhanced throttle response. A third circuit is also beneficial on a bracket car that falls out of the converter after the shift.”

On track benefits aside, three-circuit carbs aren’t intended for street cars that aspire to be race cars.

“A three-circuit carb runs rich at idle, so they’re not the best choice for street cars,” Benoit said. “For smaller displacement street engines, it’s much easier to make a two-circuit carburetor work well on the street. Just like you never want to lie to your doctor, you never want to lie to your carburetor guy, either. You can’t tell him that you’re making 1,000 hp when you’re only making 500. For a heavy-duty nitrous car, a high-end circle track car, or a 500 c.i. drag car, go with a three-circuit carb. For street cars, a two-circuit carb is a better choice.”

We’ll share Quick Fuel’s knowledge on booster design in a future post, but if you’re in need of some carb knowledge right now, we urge you to check Quick Fuel’s own tech blog for all kinds of good info!

Im building a pro street car with a BBC engine in it and ive always what to know what the difference between two and three circuit carbs was and where it can be used.

A three circuit Holley does not run rich at idle, it does run rich off idle when the intermediate circuit starts coming in,and I agree for the street a two circuit is best and more fuel efficient, very good article.

This is a very informative blog, thanks for sharing about these carb science two circuit vs three circuit metering systems race applications. It will help a lot; these types of content should get appreciated. I will bookmark your site; I hope to read more such informative contents in future… great post!!

IDLE circuit,(fuel from below the primary butterflies) MAIN JET circuit(fuel drawn up by engine vacume and released above the blades through eithera “down leg boosters or annular discharge boosters),and ACCELERATOR pumps and nozzles,

The main 3 circuits, not to forget the “inner and outer air bleeds”. I’m learning….

I’m thinking about building a carb with the 1050cfm 1.750″ butterflies throttle plate with the 750 cfm main body with annular discharge booster. My thought…smaller diameters of venturies to larger throttle blades, increases flow past annular boosters, atomizing the gas/air mixture.

Am I on the right path ?