Before the advent of the trans-brake, racers using automatic transmissions were at the mercy of the foot brakes installed in their respective cars. The stick shift guys had a big advantage, because they just had to engage the line lock (Roll Control) to leave consistently at an engine rpm where the car worked the best.

Then the transmission brake came along.

This then-revolutionary device allowed an automatic transmission car to consistently leave the line at a reasonably high rpm and consequently be “on the converter.” It also fixed the issue we all faced with brakes that couldn’t hold a car when staging. In short, the trans-brake evened the playing field between stick and automatic racers and truly changed drag racing forever.

When the trans-brake came out, there were a couple of different formats: the electric internal brake and the external CO2 setup. The pages of NHRA’s National DRAGSTER were sometimes filled with “trans-brake war” ads – manufacturers claiming their trans-brake was more consistent, more reliable, and had a quicker, faster release. While there were no clear winners at the time, you’d be hard pressed to find a CO2 brake. The electrically operated brake is the norm.

How does a trans-brake work?

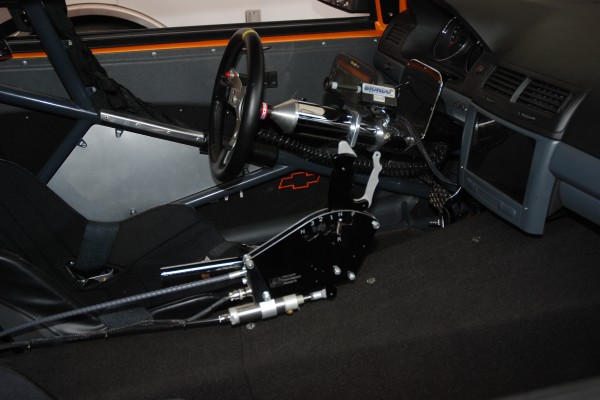

Basically, it’s centered around a solenoid, or electrical valve, that fools the transmission into thinking it is in both first and reverse at the same time. This allows you to sink the gas pedal into the floor after you’ve staged the car in gear. On a sportsman tree, as the last yellow goes out, you release the trans-brake button and the transmission solenoid releases. Consequently, the car leaves the line with the engine spinning at a pre-determined rpm.

That’s the simplified version; however, there are a few things to keep in mind. If you have the tach pegged and keep it there with the brake on, converter life isn’t exactly good. Many trans-brake manufacturers actually suggest you pre-stage in 1st gear. When you’re ready to stage, move in and find your spot. Immediately press the trans-brake button but remember to keep your foot on the brake pedal. Wait for a split second in order to give the brake time to engage. As far as rpm is concerned, higher doesn’t necessarily mean better or faster.

According to the folks at Rossler Transmissions, most combinations prefer to the leave off the trans-brake at between 3,000 and 5,800 rpm. Most seasoned racers will tell you to begin testing your preset launch rpm at a low rpm figure and work your way up. The ET slip will tell you what speed your car likes best. Typically, higher rpm doesn’t always equate to faster. You’ll also find that a two- or three-step rev limiter will be your friend with a setup such as this. That way, you can concentrate on driving rather than the tach.

When racing off the top bulb (for example, with a delay box or on a Pro tree), Rossler recommends that you concentrate on the top bulb only: “Once you see the top bulb flash let go of the brake button, and then hit the accelerator. By pushing the accelerator after you let go of the brake button you will save a lot of wear and tear on your torque converter, and make the transmission run a lot cooler.”

If you’re leaving on the bottom bulb, Rossler recommends you concentrate on the last yellow bulb once the car is staged and the brake is engaged: “You will see the top bulb flash with your peripheral vision. When the first light flashes, hit the accelerator and then, on the last yellow, let go of the brake button.”

How difficult is it to hook up an electric trans-brake?

When it comes to wiring up their Compu-Flow trans-brake, ATI offers these suggestions: “ATI uses the transmission case as ground, assuming most race cars use solid mounts on both engine and transmission. If by chance this is not the case in your application, be sure that your engine is grounded properly to the frame. The Compu-Flow Trans-brake draws only 1 amp when activated; therefore, an 18 gauge wire can be used as a hot lead to the external connector on the transmission case. We do recommend, however, that the 12-volt be fused for safety.”

ATI also recommends hooking up your trans-brake in tandem with the a roll-control system: “Although not mandatory, we have found that hooking up the trans-brake in conjunction with a roll-control system allows the car to stage perfectly at any rpm. If your car does not have a roll control system in it, any quality micro-switch will do the job.”

Factors Effecting Reaction Time

A lot has been claimed in regards to reaction times with a trans-brake. Certainly, some are quicker than others, but ATI tells us there are a lot of factors that can have an influence upon reaction times. These include:

- Position the driver stages the car in relation to the racetrack timing lights

- Type of trans-brake button, its location, and when the driver releases it

- Release speed of the trans-brake

- Weight of the racecar

- Horsepower of the engine and the rpm where it produces peak torque

- Stall speed and torque multiplication characteristics of your torque converter

- Gear ratios of the transmission and the rear-end

- Type of chassis and suspension, its setup and adjustment

- Diameter of the front tires

- Drag slick size, sidewall construction, rubber compound, age or condition, inflation pressure, and width of rims on which they are mounted

- Type and positioning of race track timing lights.

- Track surface conditions

As you can see, there are number of things that can influence how your car leaves with a brake. The good news is there are plenty of variables you can work with to improve the way your car works on or off the trans-brake.

Proper Trans-brake Use and Maintenance

Most brakes only function in first gear (confirm with the manufacturer). This means if you inadvertently hit the switch while the car is in another gear, the internal solenoid won’t engage. When engaging a trans-brake, it should only be done when the racecar is at a complete stop.

In some cases and under certain conditions, you might want to run the car off the foot brake instead of the trans-brake. If that’s the case, simply turn off the power supply switch and there will be no adverse effect on the transmission.

If your trans-brake shows a delay or has a hesitation when it releases, the first place to look is the transmission fluid. Low fluid levels will cause a delay in the trans-brake release. If the fluid is adequate, then inspect the release switch. If the switch is fine, then you should remove the trans-brake solenoid and check for dirt or debris.

There’s no real trick to running a racecar with a trans-brake; however, you’ll want to brace yourself when using it.

The launch can be violent!

[…] When the trans-brake came out, there were a couple of different formats: the electric internal brake and the external CO2 setup. The pages of NHRA’s National DRAGSTER were sometimes filled with “trans-brake war” ads – manufacturers claiming their trans-brake was more consistent, more reliable, and had a quicker, faster release. While there were no clear winners at the time, you’d be hard pressed to find a CO2 brake. The electrically operated brake is the norm. Read More […]

I have a turbo 350 with a trans brake. When I bump the car in to stage it rocks back and forth. Is there a way to adjust the brake so it dosen’t do this. Thanks Dave Hagen

Use your foot brake slightly when you bump it.

just make sure you are totally stopped before you hit the button and that won’t happen

Great job on explaining this

Im thinking of running a brake in the small engine car,im basically interested in street use and how much stall is needed to utilize a brake,and run into excessive stall RPMS, because everybody know deep stalls are not street friendly

I drive my Sonny Leonard BBC 605cui. 378 miles to visit their shop in Lynchburg, Virginia often. With that said my cars are not trailer Queens even though they have trailers

for long haul. 200mph club cgiles iii

Everytime I go to use my Transbrake, my car stalls. I have a 93 fox body. Any suggestions?

Buy a Chevy

Another GMbecile

Mine was too. I noticed (Holley efi) it would put it in cells where timing would change and therefore try to correct creating a surge. If that’s the case for you make sure to make timing the same where the indicator goes as well as all the surrounding cells

First time ever getting a car with a transbrake so I need help using it

When I get to second light do I hold the gas and brake down hit the transbrake button and let go of the brake pedal then when it lights up let go of the button or do i have to keep holding the brake and let go of both ay the same time ?

[…] trans-brake is installed in the valve body of an automatic transmission and its basically a solenoid, an electric circuit that controls the flow of the hydraulic fluid, as well as the position of the other valves. The shifter is placed in the gear before the […]

How can u test trans break without in gear ?

Good basic explanation of trans brakes and how they work.

Thank you.

My trans goes in to 2 gear As soon as I let go of the trans brake button I only get second and third gear through the quarter-mile

Hired a garage to install transmission I had rebuilt. Garage sent a tow truck to get me tow truck. It’s 1997 Ford f super duty with 19ft bed. Towed it 7 miles. Left driveline attached to rear end and also attached to transmission brake. Driveline broke loose did a bunch of damage. But within week of getting it back the transmission cracked. Got a new one with new torque converter installed. Within 4 days that transmission also cracked. They seem to be cracking around the bolts and the top of transmission under cab. Last transmission is under warranty. But don’t want to replace until we find what is causing it. Could my trans brake be damaged and the cause? If I install new transmission with trans brake damaged what will happen?