I’m having a hard time with the 750 vacuum secondary Quick Fuel Slayer carburetor on my low compression 455 Olds. The engine has a mild 218/218 cam and good manifold vacuum at 13.5 in/Hg. I checked the ignition timing and it looks good. It ran great with a 600 cfm Edelbrock carburetor.

Once I switched over to the Quick Fuel carb, it runs terribly rich and rough (the spark plugs are black) and I can’t even drive it out of the garage. I disassembled the carb twice looking for debris or dirt but everything seems okay.

All jets are stock and the power valve is the stock 6.5 and seems perfect for the idle vacuum. The float level is in the middle of the sight glass. There is no fuel pressure regulator as I am using a stock fuel pump.

I hope you have some ideas. Thanks,

D.L

We will assume that this is not a brand new carburetor but rather a used carburetor that you acquired. Our experience with buying any used carburetor at a swap meet is that it’s for sale for a reason—it won’t run correctly and the previous owner completely screwed it up trying to get it to work right.

As a prime example, we bought a used 750 vacuum secondary Holley to use for a magazine dyno test. After disassembling it, we discovered all the jets, power valves, and a few other small parts were completely missing—so it necessitated a complete rebuild.

Once that was accomplished and we put the carb on the engine on the dyno, the carb worked great at wide-open and part throttle but refused to idle. It took us over an hour of cleaning the idle passages to open up the circuit to allow the carb to idle properly. So unless you are comfortable with spending tons of time with a used carburetor to try and save it, you might be far better served to just purchase a new carb and be that much happier right out of the box.

But back to your problem. The first thing to check is to look to make sure there is no fuel dripping into the engine from the boosters at idle. This often occurs because the float height is abnormally high. You mentioned that the float height was correct but we’re trying to cover all the bases just so we don’t miss anything.

Next, we will also assume that the idle mixture screws are properly adjusted. They should be placed between 1 and 1.5 turns out from gently seated in the metering block. If all these situations are correct, then we can move on to other areas.

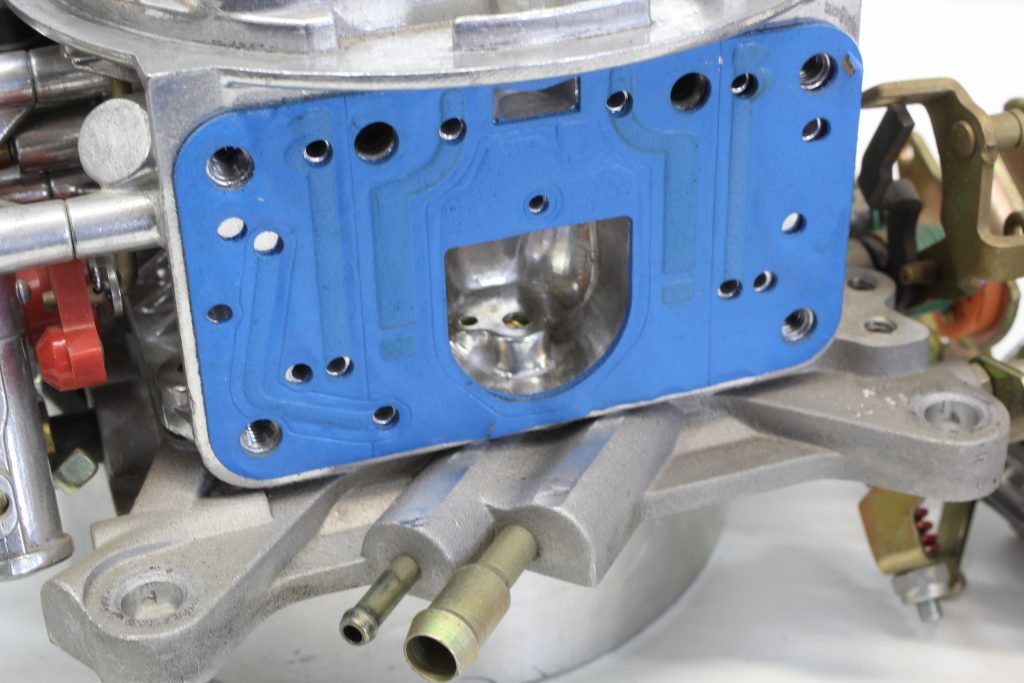

You mentioned the power valve is a 6.5. The rating stands for the inches of mercury rating for manifold vacuum when it will open. Here’s our first test. Drain the primary float bowl by removing one of the lower bowl screws and catching the fuel with a small cup. Remove the bowl from the carb and peel the primary metering block away from the main body of the carburetor. Inspect the cavity in the main carb body looking for raw fuel. This cavity should be dry. If the cavity and that side of the power valve is wet with fuel, we have our first clue. Something in or around the power valve is allowing fuel into this cavity which will immediately find its way into the intake manifold, making it run excessively rich.

Most people will immediately point to a defective power valve and this is often the case. There is not a simple, backyard way to check for a blown power valve. Moroso makes a power valve checker where the valve is threaded into a receiver that is sealed off and vacuum is applied. If vacuum will not hold on the top side of the valve, then the valve is defective and must be replaced. Most of the time, it’s just easier to buy a new power valve and replace it and see if this eliminates the problem.

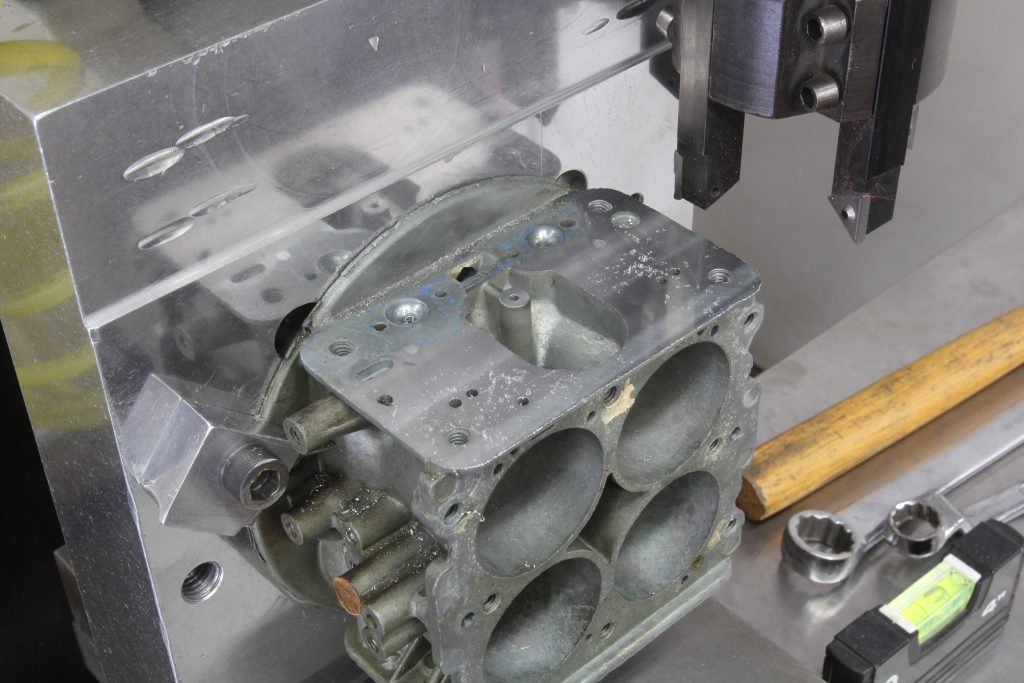

Often times, according to our friend Sean Murphy at Sean Murphy Induction (SMI), the metering block surface of the carb main body can be distorted by excessive bowl screw tightening. This will distort the main body enough that the main body gasket will not properly seal the power valve to the main body and a fuel leak may occur. If this is the case, the only real cure is to send the carburetor to SMI or any other reputable carb rebuilder who can mill the main surface of the main body to ensure it is flat. This is a common problem with Holley style modular carburetors.

Another thing is to check to make sure the power valve gasket is seated properly. We’ve often seen where inattentive installers will not allow the power valve gasket to seat properly as they are tightening the power valve into the metering block. This will also cause the power valve to leak.

If the carb has sat for a long time, it’s also possible that the power valve has become brittle after the fuel evaporated. This is a common problem but it’s also an easy fix just with a new power valve. We prefer to use the newer, green Viton rubber diaphragm valve that Holley offers as it is far more durable.

If your own investigation does not turn up the obvious solution, you can certainly call Sean at SMI and consult with him on how to repair your problem.

Comments