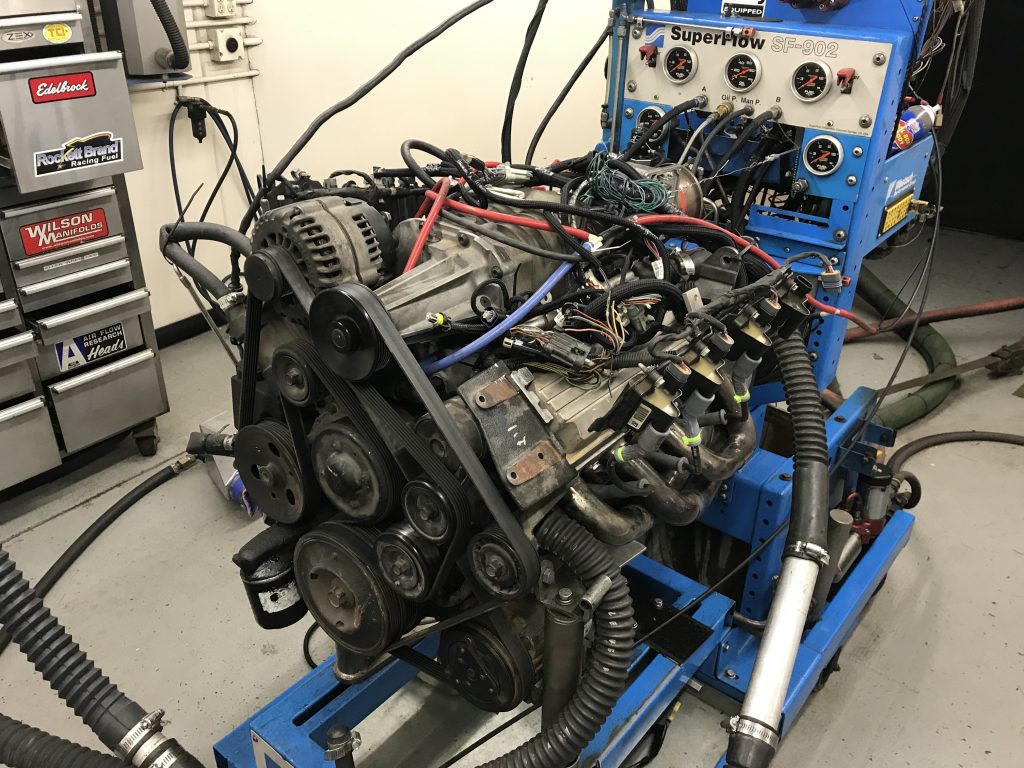

The only thing better than going to the junkyard and grabbing a running motor is to grab a running motor with boost.

While our supercharged Pontiac/GM 3800 Series-3 L32 certainly qualified on both accounts, it was actually lacking slightly in the running department when we made our initial dyno pulls. Sure, it ran, and there was boost, but the power was certainly down from where it should have been given its rated output of 260 hp.

In truth, this was actually our second attempt at junkyard boost, as our first netted the predecessor of our L32, the 240-hp L67 3800 Series-2 V6. Unfortunately, the L67 was down more than a few holes and thus a suitable replacement became mandatory for our Junkyard Boost dyno adventure. After the initial pulls on the L32, we eventually removed and repaired the stock cylinder heads. Thanks goes to Derrick and the gang at L&R Automotive for the quick turnaround on the heads.

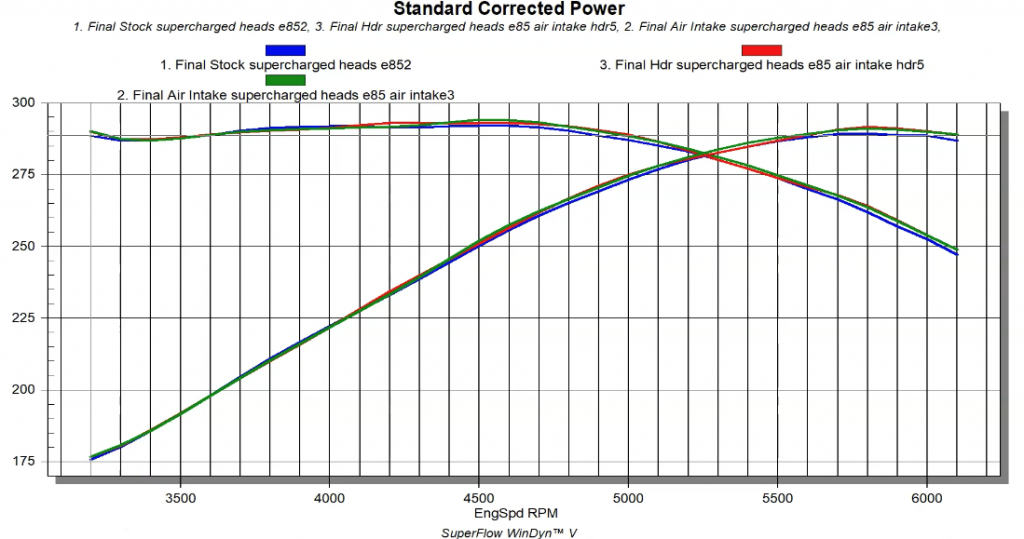

After the installation of new valve seats and a fresh valve job, the heads were reinstalled on the awaiting V6 with impressive results. For a full rundown video on the head test, as well other as all the results on this test motor (compound boost!), check out the Richard Holdener YouTube Channel. With 80 pound injectors and a Holley HP management system, the otherwise stock L32 produced 289 hp and 292 lb.-ft. of torque at a peak boost of 9.7 psi.

Improving Power at the Intake

After establishing the baseline, we started looking for ways to improve the power. Knowing that more airflow into the blower equals more boost and power out of the blower, we decided on a radiused air intake as the first modification to the supercharged, junkyard V6.

Pulled from a 2004 Pontiac Grand Prix GTP, the supercharged L32 featured an electronic drive-by-wire throttle body. We replaced the electronics with a simple cable by welding on a throttle arm. This allowed us to mechanically open and close the throttle body. To improve the flow rate of the throttle body, we installed a radiused air inlet using a silicone coupler. While this set up certainly improved the flow rate, the same can’t be said for power production, as the air intake managed to increase the peak power by a scant 2 horsepower (to 291 hp) and 2 lb.-ft. (294 lb.-ft.).

Apparently, the stock throttle body had no trouble supplying the necessary airflow requirements at the stock power level. It should also be pointed out that the motor was run with full accessories, run on E85, and tuned to perfection with the Holley HP management system. The installation of the 80 pound Accel injectors was deemed necessary to supply the additional fuel flow required not only for the use of E85, but we would eventually run more boost and even add a turbo in part 2 (compound boost) coming soon!

Upgrading the Pontiac 3800 Exhaust System

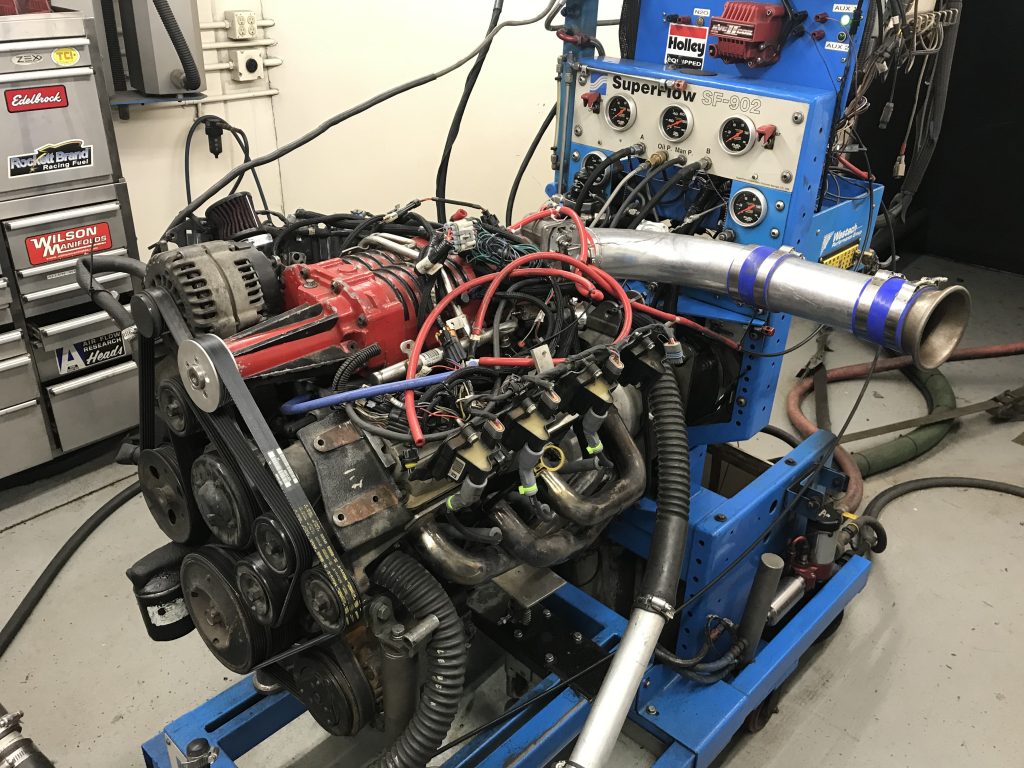

Since the inlet side of the supercharged 3800 netted no power gains, we turned our attention to the exhaust side, and decided to replace the stock exhaust system, including the front, factory cast iron exhaust manifold, the cross-over pipe, and rear manifold and exhaust outlet.

One look at the design of this system should just scream “turbo me!” But instead, we replaced the stock components with tubular headers. Headers are a popular upgrade for the FWD 3800 motors, but we wanted to see just how much power they were actually worth. The only component retained in the header swap was the three inch exhaust used after the three inch V-band. The dreaded factory downpipe was even replaced, as (according to internet lore) this was a sure source of exhaust restriction. The tubular headers offered little in the way of primary length (think of them as a mid-length header at best), we nonetheless had high hopes for power.

Unfortunately, like the air intake, the headers offered only minor changes in power. What did happen, which might certainly be beneficial, is that the exhaust modification actually dropped the peak boost pressure from 9.7 psi to 9.1 psi. We wanted more power, but we will also accept the same power at a lower boost level if it means reduced knock retard in the vehicle.

More Boost!

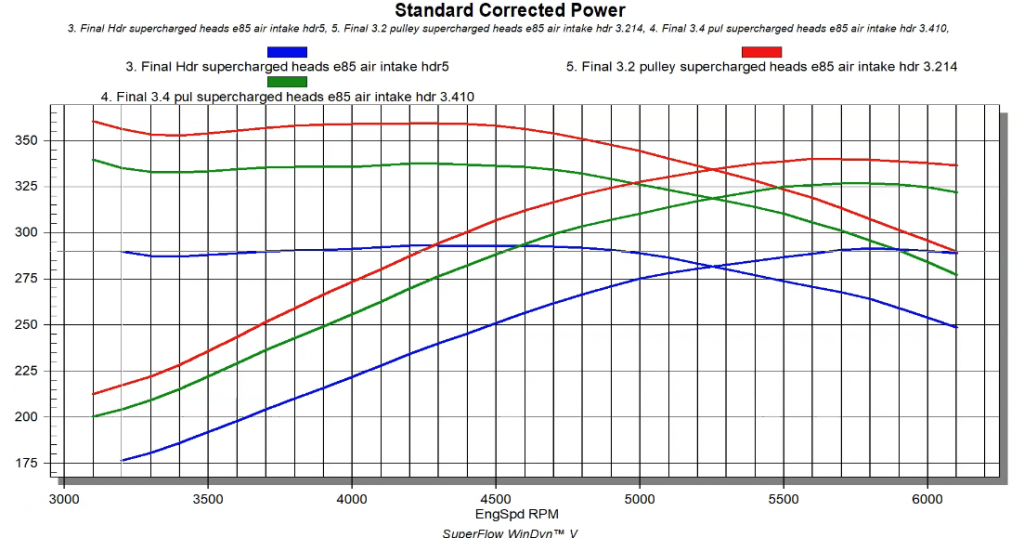

We obviously saved the big gains for last, as the best way to improve the power output of a boosted junkyard motor is to add more boost!

To that end, we replaced the factory Gen-V blower with another (factory) Gen-V blower. Why the seemingly redundant blower swap? Well, the replacement blower featured a pressed-on drive hub ready to accept bolt-on blower pulleys. Smaller blower pulleys increase the speed of the blower, which adds power and boost.

To get things started, we installed a 3.4 inch blower pulley. This resulted in a jump in boost pressure to 12.8 psi, which pushed peak power to 326 hp and 338 lb.-ft. of torque. As we have come to expect, the pulley swap netted power gains through the entire rev range, from top to bottom.

The next pulley swap, to the smaller 3.2 inch pulley, followed suit, increasing the boost pressure to 15.1 psi. The 3.2 inch pulley increased the power output of the 3800 to 340 hp, while the peak torque checked in at an impressive 359 lb.-ft..

No wonder smaller blower pulleys are one of the most popular upgrades available for not only the supercharged 3800 V6, but for most factory supercharged applications. Check back for part 2, where we add even more boost with a single turbo feeding the M90 supercharger. Make sure to check out all the 3800 upgrade videos on my YouTube Channel.

The head gasket on the left/radiator side for a FWD, is installed incorrectly, the arrow & Front Indicate placement. I really like the 3800 Buick®️

Good Eye Stevie,Do you think it was just upside down?

Thanks,Richard,love watching your stuff,I have a 1997 Regal GS with the series 2 L67, fun little car,you showed me with your dynos these motors are under rated,like many other gm engines.

Awesome stuff Richard. Your articles are fantastic, all of them.

Id love to see your boost curve here and know what timing was ran on this out of curiosity. That is if your not too busy to get back with that info. Thanks!

***you’re

Would these mods work as well on a Trofeo?

I have question on the actual boost pressure as I have a 2000 SEE I with a fully ported tract, gen 3 m90. I haven’t finished upgrading my exhibition as yet aside from a larger in shop made down pipe and stainless front manifold. The gauge in my dash has never indicated over around 9.5 psi and I have a 3.4 pulley. I realize this may not be truly accurate. Is the gen 5 that much better at making boost over a gen 3?

We’re did u get the pully? Link it plz?and is it better then stock and what’s the dif

My Buick 3.8 has stage 3 cam big valves 7.1 rockers long tube headers idles at 975 rpm ,has a 3.0 pully compression 170 ish sounds and runs good , but I only have 9 #s of boost. It just doesn’t have the power that it used to have. It’s in a 1600 hundred # car with 2 speed power glide . I checked for vacuum leaks . What would make my car lose boost ?