I’m building a Chevy 350 engine for my son’s circle track race car. I started out with a 0.040-over block that I think has been severely decked but I’m not sure how much. I also bought a used forged crank and new H-beam rods and forged 11:1 floater forged pistons. I discovered that the crank is a 3.50-inch stroke instead of 3.48-inches because some of the pistons now stick out of the block.

I’m very concerned about the piston-to-head clearance. I bought a set of Fel-Pro 1144 gaskets set at 0.051-inch thickness. Some pistons are 0.014-inch out of block so I was figuring I had about 0.036-inch piston-to-head clearance. The class rules dictate the engine cannot run over 6,800 rpm that is set with a chip. I’m doing all of this on a very limited budget. Do you think this build will be okay or is it going to be a grenade ready to explode? Thanks.

…

Jeff Smith: This is always the risk when assembling an engine with used or unknown components but I don’t think this is a grenade as long as you pay attention to the assembly.

Let’s walk through the process of what happened. The issue is that the pistons extend past the deck.

You mentioned that you thought the block had been severely milled. You didn’t mention the actual pistons that you used, but we’ll create a typical example and see what the numbers tell us.

An easy way to determine approximate piston to deck is with a simple formula. To determine piston to deck, we add rod length plus piston compression height plus half the stroke.

Since we don’t know your piston manufacturer, we’ll use a forged, Speed-Pro piston flat top piston intended for a 350 Chevy. This piston has a compression height of 1.565 inches. This is the distance from the wrist pin centerline to the piston’s deck surface.

This piston is intended for a 5.70-inch rod length. Our final piece of the puzzle is deck height. A small-block Chevy’s standard deck height is 9.025 inches. To determine the half stroke, we divide 3.48 by 2 = 1.74 inches.

The equation looks like this: 1.74 + 5.70 + 1.565 = 9.005 inches.

If the block deck height is 9.025, this theoretically puts the piston roughly 0.020-inch below the deck. Most piston manufacturers assume that the block will be decked around 0.010-inch. If our block in this exercise had been milled 0.010-inch, this would still place our piston 0.010-inch below the deck surface.

You mentioned that your crank was a true 3.50-inch stroke crank. This adds 0.020-inch to the stroke, or 0.010-inch to the overall stack height of the piston and rod.

We looked up a set of JE pistons for a 5.7-inch rod 3.48-inch stroke that specs 1.560 inches for compression height.

Here’s the math: 3.50 / 2 = 1.75 + 1.560 + 5.7 = 9.010 – adding another 0.005-inch. So it does appear that your block has been milled quite a bit.

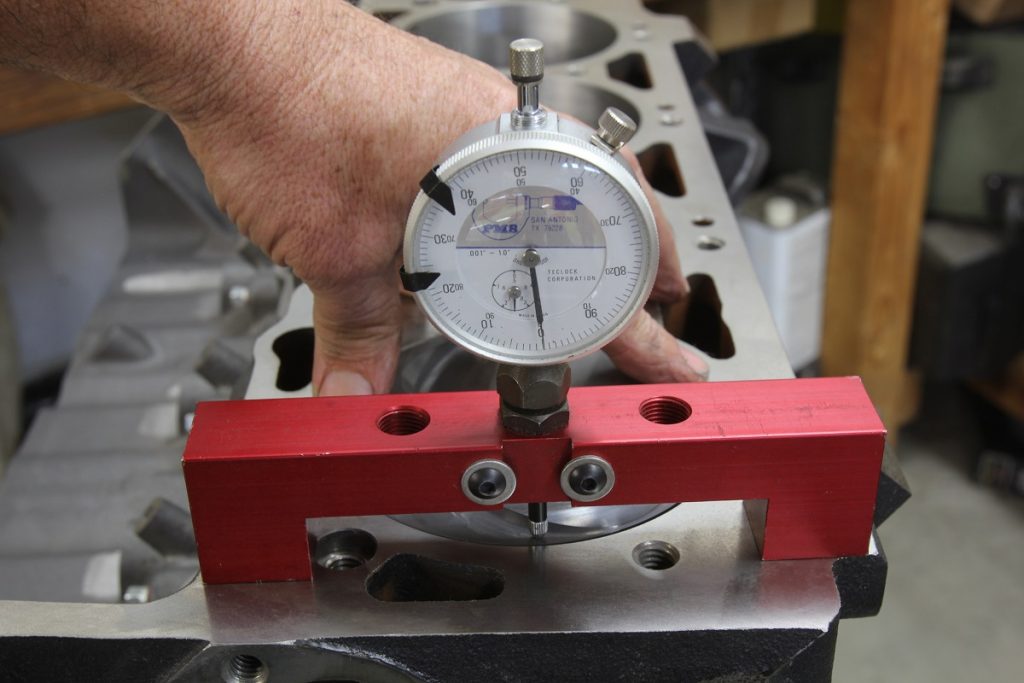

You didn’t mention exactly how you measured the piston-to-deck height with the pistons sticking out of the bore. This can affect the results.

All pistons will rock or move at top dead center (TDC) by pivoting around the wrist pin. If you measure the deck at 90 degrees from the wrist pin, this is where the movement will be most pronounced. Because of this movement, the best way to measure the deck height is at the wrist pin centerline. This will be minimize the effect of piston rock.

If you measured the piston with it cocked in the bore at 90 degrees to the in with the piston at the peak of its movement, this can be as much as 0.006- to 0.008-inch (or more) compared to what it would measure above the wrist pin.

Of course, it’s also possible that you measured the piston on the depressed side and that your actual piston height is actually more than stated at 0.014-inch. So you can see that the way the piston height is measured is extremely important.

If you can’t measure the piston at the wrist pin centerline, the next best approach is to measure the piston rock at both ends — up and down and then average the two. So if the piston measures 0.020-inch rocked down and 0.010-inch with the piston rocked upward, then the average would be 0.015-inch.

To help you with the solution, we’ll assume that you measured deck height at the wrist pin centerline and that the tallest piston is 0.014-inch out of the bore.

As you mentioned, Fel-Pro makes an 1144 gasket that specs at 0.051-inch compressed thickness. Subtracting the piston height above the deck from the gasket thickness, we get a true piston-to-head clearance of 0.037-inch. This is an acceptable clearance. One of the reasons for this clearance is to accommodate piston rock across TDC as well as to assume that at engine speeds above 6,000 rpm that the total piston and rod assembly could “grow” by a few thousandths.

One other concern is it would be worthwhile to also know how far the top ring land is from the top of the piston.

Some piston companies move the top ring land upward to reduce what is called the crevice volume. A typical distance will be roughly 0.200-inch from the top of the piston to the top of the top ring land. It’s worth looking at.

It’s best to measure everything before assembling the engine to ensure that everything will work as intended — especially the way you measure the piston deck height. But if your numbers are correct, this should work out okay.

[…] I’m building a Chevy 350 engine for my son’s circle track race car. I started out with a 0.040-over block that I think has been severely decked but I’m not […] Read full article at http://www.onallcylinders.com […]

Jeff is a real asset to any organization he is associated with.

Jeff, you are doing a superb job am an animator by profession and doing job at https://www.videocubix.com/ my hobby is to modify old cars can you help me in buying some old mustang models

One other thing to consider is that he might be measuring the piston’s dome when trying to determine the deck height. He said his pistons are 11:1 compression ratio and it’s highly unlikely to come from flat top pistons. The dome could result for what he assumes is the piston sticking out. Granted, if he put clay on top of the piston and mocked the head up with a gasket onto a block, the clearance is the clearance Clarence.