(Image/Wayne Scraba)

You’d think selecting a rear end for a project car would be easy.

It’s not.

Browse Summit Racing’s website or catalog and you’ll discover there are almost too many choices.

For example, on the GM side, you’ll find 8.20-inch ring gear 10-bolts, 8.50-inch ring gear 10-bolts and 8.875-inch diameter ring gear 12-bolts.

Popular FoMoCo choices include the 8.00-inch ring gear rear end, the 8.8-inch ring gear read end and of course, the 9-inch.

For Mopars, the 8¾ and Dana 60 reign supreme. And then there’s the Dana 44 and others including several quick-change assemblies.

The options are many.

But it gets easier once you narrow it down to the top three choices:

- The Dana 60

- The GM 12-bolt

- The Ford 9-inch

There are several reasons the “Big 3” prove popular, ranging from outright strength to parts availability. And equally important, the aftermarket now has you covered when it comes to these popular and time-tested rear axle assemblies. You don’t have to scrounge junkyards for any of them, nor do you have to mess with worn out 40-year-old components.

In no particular order, here’s what’s hot and what’s not with regard to all of them.

…

Dana 60 Rear End Assemblies

Strange Engineering came up with the idea of actually improving upon the vintage Dana 60. Their version (the “S60”), is available in any number of configurations from a bare housing without ends and brackets to a bolt in housing (as shown here) all the way up to a complete rear axle assembly. (Image/Wayne Scraba)

If you want a big brute of a rear end under your car, look no further than a Dana 60.

Even in the heyday of muscle cars, Dana 60 rear differentials were renowned for their strength, along with their difficulty to locate.

Today, they’re actually incredibly easy to find. Strange Engineering and others offer a full range of heavy duty, bolt-in rear end assemblies for a large number of popular applications.

The truth is, for racing purposes you can now build a better rear than a Dana, but for street cars, it’s a good choice. Here’s why:

Dana 60 rear ends are equipped with a huge 9¾-inch diameter ring gear and when fitted with a contemporary limited-slip setup (there are several, including Detroit Lockers), the axle splines increase to a hefty 35.

The pinion is a large 1-5/8-inch diameter affair (29-spline) that can be set up to accept massive Spicer 1350-Series universal joints. Gear ratio options are plentiful too, ranging from 3.31:1 all the way up to 7.17:1.

Strange Engineering’s Dana 60 (dubbed the ‘S60’) isn’t exactly a piece-by-piece clone of the original.

In a conventional Dana 60 this large support doesn’t exist. Strange added this material where it counted and shaved bulk off the exterior of the case. Overall, the S60 case is thicker than a standard Dana 60. (Image/Wayne Scraba)

Instead, it comes with several user-friendly modifications.

For example, there’s extra material under both main caps (similar to some aftermarket 12-bolt housing). That means you don’t need to add billet caps to the rear end. In a standard Dana 60, the axle tubes are simply pressed into place and plug welded. The Strange S60 on the other hand has the tubes cleanly rosette-welded and then each tube is welded completely to the case. Stock Dana 60 rear ends usually require the case to be spread in order to remove the carrier (some more than others).

That’s not the case with an S60—it doesn’t have to be spread to re-install the carrier since it is equipped with adjusters like an aftermarket 9-inch, which eliminates the side carrier shims.

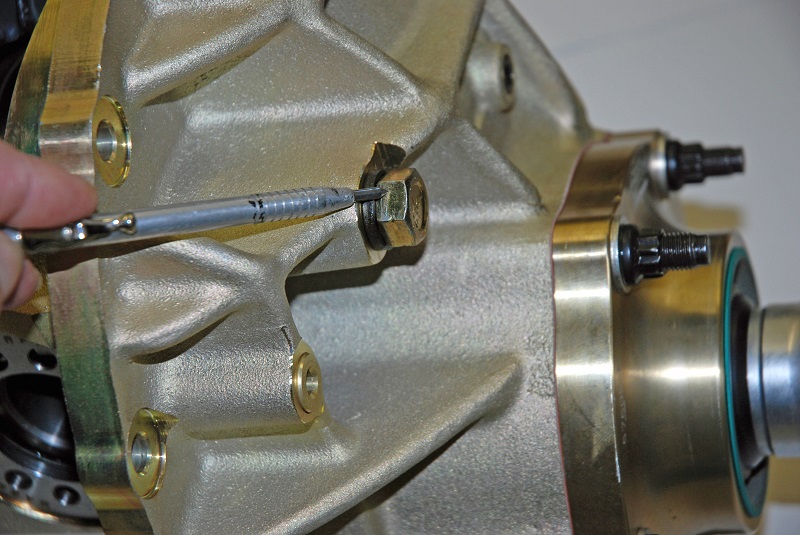

Strange includes these internal adjusters as standard equipment in the S60 case. This means you don’t need to spread the case to re-install the carrier since it is equipped with adjusters like an aftermarket Ford 9-inch. This means the side carrier shims are eliminated. (Image/Wayne Scraba)

…

GM 12-Bolt Rear End Assemblies

This is an aftermarket 12 bolt. The area behind the main caps is solid (instead of hollow) and the caps are massive. Because of this, there is no need for a billet cap or a rear cover girdle. (Image/Wayne Scraba)

One of the most popular high performance rear ends in use today is the 12-bolt Chevy.

But it too (like the Ford and the Dana) has shortcomings.

For example, the area behind the rear caps in a stock GM 12-bolt casting is heavily scalloped (more or less hollow). This compromises strength. The fix is to use a billet main cap.

Why go to all of this trouble? Simple. The hypoid action of the rear diff tries to force the carrier backward, out of the housing.

Another is the limitation of the bore size. The bore size of the case determines which axles you can use. Keep in mind that when an axle spline is increased the diameter of the axle shaft increases (which in turn dictates the need for a special large bore case). In stock form, you can squeeze in a 33-spline axle, but that’s it. Certain new aftermarket housings can be built to accept a big 35-spline setup. And many of those don’t require billet caps.

In a stock 12-bolt, the axle tubes are held in place only by plug welds.

When looking at vintage 12-bolts, you’ll find that in many cases the factory GM welds weren’t sound and, under close examination, you’ll find pinholes in the welds. This doesn’t compromise the strength of a housing such as this (since the tubes have been totally welded to the coconut), but it does create one small problem: The factory spot weld system will often leak or ‘weeps’ lubricant.

Because of this, many car owners have had their 12-bolt seals replaced, gaskets replaced, and drain plugs swapped—only to end up discovering that the leak was in the area of a factory spot weld.

When it comes to 12-bolt housings, this is one of the weak spots: GM used plug welds to attach the axle tube to the housing. Here, the axle tubes are welded directly to the (much stronger) aftermarket iron case. (Image/Wayne Scraba)

The solution is simple, but time-consuming. Each tube spot weld location is filled with a plug weld or ‘rosette’ weld process, which results in a clean, leak-free housing.

One other area you should take note of is the entry point for the axle tubes in the coconut. In a stock 12-bolt, this spot is fragile. In the case of aftermarket castings, they’ve been seriously beefed up to handle much larger loads than a stock GM 12-bolt.

Another issue is the stock C-clip method of axle retention.

C-Clip axle retention is problematic on 12 bolts. In stock form, the inner portion of the axle (ahead of the spline) is machined for a simple C-Clip to hold it in place. With this arrangement, if an axle breaks, it can easily depart from the housing. This aftermarket housing uses an integral C-Clip eliminator setup. In the second photo, you can see the basic components used to secure the axle to the housing (obviously, no C-Clip is used). Below the axle and from the left: Bearing lock ring, bearing, seal and axle retainer. (Image/Wayne Scraba)

Break a C-clip retained axle and the entire axle will depart from the car. That’s why C-clips are required by every racing association. The solution is either a C-clip eliminator kit or a weld-on housing end that uses a sealed bearing and bolt-on bearing retainer.

Of course, the majority of aftermarket 12-bolt housings are already set up for the sealed bearing and bolt-on bearing retainers.

…

9-Inch Ford Rear End Assemblies

Ford housings usually mandate some sort of brace when stirred in with sticky rubber and brute power. The reason for bracing a Ford housing is because they tend to want to move fore and aft (flex on the ends). (Image/Wayne Scraba)

The 9-inch Ford is definitely a very popular rear differential, but you have to remember that the 9-inch hasn’t been built for decades, which means the newest junkyard parts you’ll come across are at least 20 years old.

On the other hand, it’s pretty much the standard go-to rear end for drag racing (and for good reason).

Aside from age, there are three major drawbacks to the 9-inch from a drag-racing perspective: First, the stock housing axle tubes aren’t round. Not only do they taper from 3½ inches down to 3 inches, but the tubes all have ‘flats’ which are more or less squashed onto the tubes.

Both of these factors force a chassis builder to custom build every bracket, because none are symmetrical.

Additionally, the OEM Ford housing face is approximately 24 inches wide. Because of this, in some cars, you’ll have to weld brackets to the face, which means you lose adjustment holes for items such as the four-link.

Most of the detailed work that goes into a good 9-inch is hidden, resulting in many of these housings look more stock than they actually are.

Many of the new aftermarket 9-inch housings mandate a ton of work.

While we can’t give you a full-blown, step-by-step investigation into the methods used to fortifying a Ford, we can give you a bit of insight into some of the techniques.

…

Because of the hypoid action of the ring gear, there’s a tendency for the 9-inch to flex fore and aft at the center section. In order to stop this, the inside of the housing is internally ‘braced.’ You can see two of the braces at the bottom of the housing. (Image/Wayne Scraba)

For high-powered cars, it’s standard practice to add a brace to the rear of a Ford 9-inch, which essentially ties the ends of the axle tubes to one another, and at the same time, anchors the back of the housing.

Doing this greatly increases the strength of the housing and keeps it from physically moving forward and aft.

But there’s a catch to the back-brace scenario, and one that some chassis builders forget, ignore, or simply don’t know about: When the back brace is added, the housing won’t deflect forward and back. Instead, under power, it deflects downward, which will can negatively impact performance and break parts.

The solution? A tube affixed between the four-link brackets (see the accompanying photos for a closer look). Of course, most builders uses custom-built 360-degree four-link brackets (that wrap completely around the respective axle tubes).

But there’s still more to the nine-inch prep.

Virtually all 9-inch housing ‘banjos’ are formed by stamping. When loaded by way of sticky tires, extra weight, and a strong engine, the construction doesn’t really work, because what ends up happening is the housing flexes at the carrier which shortens the life cycle of the ring and pinion.

A big issue is the rear cover found on the housing.

The back of a 9-inch isn’t one piece—it consists of a stamped cover pressed into the housing. The hypoid action of the third member attempts to force the carrier out the back of the housing. Welding the cover to the back of the housing won’t fix the problem.

The fix is to weld the stamped pieces of the housing together and then add internal housing ‘supports.’ These supports are essentially, a series of tubes that tie the front face of the housing to the rear. This will improve ring gear life.

What about the center section? Ford center sections were manufactured typically with a separate bolt-in support for the pinion.

If you need the ultimate in 9-inch Ford center-section configurations this is it. This is a through-bolt configuration aluminum center section, complete with a pinion support, billet carrier adjusters, 1350 universal joint yoke and more. (Image/Wayne Scraba)

Ford did something good with the design and layout of the 9-inch. No secret.

If you’re inclined, it’s possible to track down most of the stock hardware to piece together a factory-style nodular iron; 31-spline 9-inch, complete with a Daytona pinion support and even a Detroit locker.

But the truth is, what you’ll find is old, used-up hardware. And you should be prepared to drop some serious coin in order to whip the old stuff into shape. Not good. And likely not race-effective either.

There are plenty of choices out there for updated aftermarket brute-force Ford center sections.

Several companies manufacture and sell nodular iron cases. Nodular iron is a type of cast iron that first saw the light of day in 1943. While most varieties of cast iron prove brittle, nodular iron is much more ductile, because of its “nodular graphite” inclusions.

When you consider aftermarket cases, think about the availability of upgrades. Several companies (Strange Engineering and Mark Williams to name two) offer reinforced nodular iron cases which are stronger than stock, but are comparable in weight to a stock Ford assembly.

Some of the better aftermarket 9-inch cases come complete with billet steel rear end caps that have been precision-alignment bored. They also include special billet steel adjusters and studs to secure the pinion assembly. They’re available with stock and larger-than-stock bore sizes (the larger the bore, the larger the axle diameter/spline you can use—the larger the axle diameter and spline, the stronger the axle).

There are other options too including “through-bolt” aluminum case examples. Isn’t aluminum weaker than nodular iron? Not necessarily.

When hear the term “through bolt” design, this is what is being referred to: Instead of a bolt (for the main caps) threading into the body of the center section, a high strength bolt goes completely through the center section. (Image/Wayne Scraba)

These are highly refined, extreme-duty components that have pretty much become the standard in NHRA Pro Stock. It’s also used with regularity in slower class drag race cars, Pro Street cars, and any number of seriously quick street machines.

Which Rear End is Best?

9-inch Ford center sections allow for bench servicing. But you still have to wrestle them around to work on them. Here’s the solution: Simply mount one of these Summit Racing axle assembly adapters to an engine stand or workbench. This steel adapter easily converts an ordinary engine stand into a convenient axle workstation. The included attachment also allows the adapter to be bolted to a workbench. (Image/Summit Racing)

As always, it depends.

In terms of weight, the Dana 60 is the heaviest of the bunch (although the S60 is quite a bit lighter than a stock Dana 60). Typically, they are 20-40 pounds heavier than a 12-bolt or 9-inch. We can’t provide you with specific weights because housing width and parts selection will obviously affect weight.

In terms of power loss, the 12-bolt has approximately 2-3 percent less parasitic loss than a 9-inch because of the pinion location, sometimes called the hypoid centerline.

The Ford 9-inch pinion is mounted lower in the carrier and has the greatest hypoid offset, which causes it to consume more power to drive it than the Dana 60 or GM 12-bolt.

The Dana 60 has so much mass it too consumes a lot of power to drive (although many say it feels slightly less than a 9-inch Ford).

As far as servicing is concerned, the 9-inch Ford is the big winner, simply because you can remove the center section and service it on a bench (this is a big reason why it’s favoured by drag racers). But wrestling a center section around on the floor or a bench isn’t the easiest unless you have a bench stand with an axle assembly adapter.

This allows you to work on the 9-inch center section on your on your workbench or engine stand.

And finally, Dana 60 parts aren’t quite as easy to find out in the wild like you can with 12-bolt and 9-inch Ford parts.

There are many things to consider when selecting a rear end (not the least of which is your budget). All three of these rear ends are very good when built with the right parts.

What is a posi traction

Hey Rico.

Posi-traction is simply a brand name Chevrolet used for limited-slip differentials on passenger cars.

Ferrari called them E-Diff. Chrysler called them Sure Grip. Toyota called them LSD.

Chevy chose “Positraction.”

Wayne may know about it than we do. I’m sure he’ll add more if we’ve oversimplified this.

7

Ford 9 inch may take a little more power to run but you forgot why they are simply the best ! its called Hypoid distance, how many teeth are engaged in the ring gear i favor more ring gear pinion gear mesh for superior strength there is a reason why 9 out 10 cars making 1000 to 10,000 hp choose the 9″ ..Great Article keep up the good work!

The 9″ ring gear tooth may be longer and provide more tooth contactthan the Dana 60. However, horsepower loss from 2.25 pinion center line. Also, The factory 9″ will never hold up to 500 or more horsepower. After market parts must be installed including boxing the housing, tubs, center section. Or a special 10″ ring and pinion.

While you’re not wrong about the housings themselves, the third members will take a lot more than 500 horses. I’ve run a stock Nodular carrier with 4.11 gears in a 3800lb. truck with over 800 HP and had no problems. The real strength of the 9″ is the pinion support bearing inside the case. It prevents the pinion from “walking” up the ring gear, which can be a problem with so much gear contact and hypoid distance.

i really enjoyed reading all the above facts on rear ends, i’m putting a old school dana 60,that kinda concerns me a little. But we’ll see!! thanks Gene

Actually the Dana 60 can hold it’s own against the ford 9”,every ford 9” I have experimented with behind a 900 horse 440 1970 charger just didn’t quite like 8000 hole shots,that’s why I always went back to my Dana 60’s.

You really need to proofread.

“That’s why C-clips are required by every racing association.”

Using C-clips to secure the axles in the housing just doesn’t seem to be a very practical or safe way.

That’s another advantage to using a Ford 9” assembly.

They use retainer plates that are held captive on the outer ends of the axles by the pressed on bearing assemblies. The plates are securely bolted to the ends of the housing which completely eliminates the need for weak C-clip axle retainers. If a catastrophic failure of the differential or axle should occur within the housing, the axle and wheel should remain on the car, avoiding the dangerous situation of losing one of the rear wheels.

This actually happened yesterday I was driving my ram 1500 power wagon stock completely except it had a Dana 60 rear end bought it brand new I was doing 80 down a dirt road and I wasn’t even getting on it it’s a five speed 318 and the rear end just randomly blew apart and left A hole in the differential locked up my rear tires in mind you my truck has no power steering and I spun it around and because of that rear end it almost put me in a ditch that would’ve flipped my truck so Dana 60 rear ends are garbage in my opinion because I spent a lot of money on that rear end Brand New pretty much came out of a truck that had 2400 miles on it I filled it with oil yesterday morning because that’s when I finished putting in the rear end it wasn’t leaking any oil the gears were fine when I checked him and it still blew apart on me

In answer to your question, your 1500 ram did not have a Dana 60 in it. It had a corporate 9 1/4 in. I would have had an octagon rear cover. I had a 1997 ram 1500 with 1300 miles on it when the rear blew the seals on the hi-way. It caused me 2 days down time to have Fort Smith Dodge change all of the components except for the brakes and the actual housing. I did not have any further probems with taht truck. My ex sold it with 143000 miles on it, and we did put the truck thru hell. It towed 12k from California to Florida. no issues.

I also blew a 9 1/4 rear just last week in my 78 D100 Custom with a 318 / 4 spd / 2WD. I wasn’t shifting, wasn’t driving it hard – how hard can you drive a 318 with a NP435?!

I haven’t dug into the rear yet to find out what is wrong. The truck will still drive, but there is a click and a ‘bang’ on every rotation. It was so loud that my first thought was something in the bottom end of the engine, but I pushed the clutch in, the oil pressure was fine, and the banging was still there. I drove 3 miles to my house, put it on a lift, put it in gear and it did the same thing.

I’m not sure what my options are for rear ends in a Dodge truck. They don’t have the same level of aftermarket support as my C10 and F100 brethren.

Check your drive shaft it could be bent sounds just like a bad rear end. Happened to me in a mid 80s 2wd d100. Sounded like my rear end was making loud noises and it was jerking around. Convinced it was the rear axel turned out to be a bent drive shaft

What ever champ, I bet you drive a ford cortina 1.3auto that was handed down to you by pops and you dream about putting a Granada v6 in it and a borg Warner rear end…?

I had a GM 12 bolt w 4.56 gears and a ladder bar bar set up in a ’67 Chevelle SS that I sheared three ring teeth off the ring gear. Thought it was the transmission but turns out the clunking every rotation was just the sound moving up through the drive shaft. My drag racing buddy who I got some 4.10’s from said he had never seen that. At the time it was a 400 horse small block with a worked over B-W super T-10 – after already trashing the big block and M-22(“rockcrusher” my ass!). Continually snapped ladder bar bolts…. To say at launched hard maybe an understatement. Sold the car shortly after that so not sure if it continually held up. Also not sure if it was the abuse from the big block and speed shifts with an inline shifter that we can the 12 bolt or if it just wasn’t up to the task. Couldn’t go to a Ford 9-in though. I just have a problem putting different brand products and different vehicles lol.