(Image/Jeff Smith)

I just bought a ’68 Olds Cutlass from a local guy. It’s in really great shape and I got a good deal because the previous owner was fed up with an electrical problem. He was straight with me – he said that sometimes you’d be driving down the road and the whole car would just die – everything. He’d pull over to the side of the road and sometimes the car would start back up and other times it was like the battery was completely dead even though the battery was fine. After having it towed home too many times and not finding the problem I guess he decided to move on. The car has done it to me a couple of times now. A friend says he thinks the alternator is the culprit, but I’m not sure.

A.F.

It sounds like you’ve made a pretty good deal because the solution is fairly simple.

There’s a quick and easy fix or one that is a little more expensive. Let’s start with what’s causing the problem.

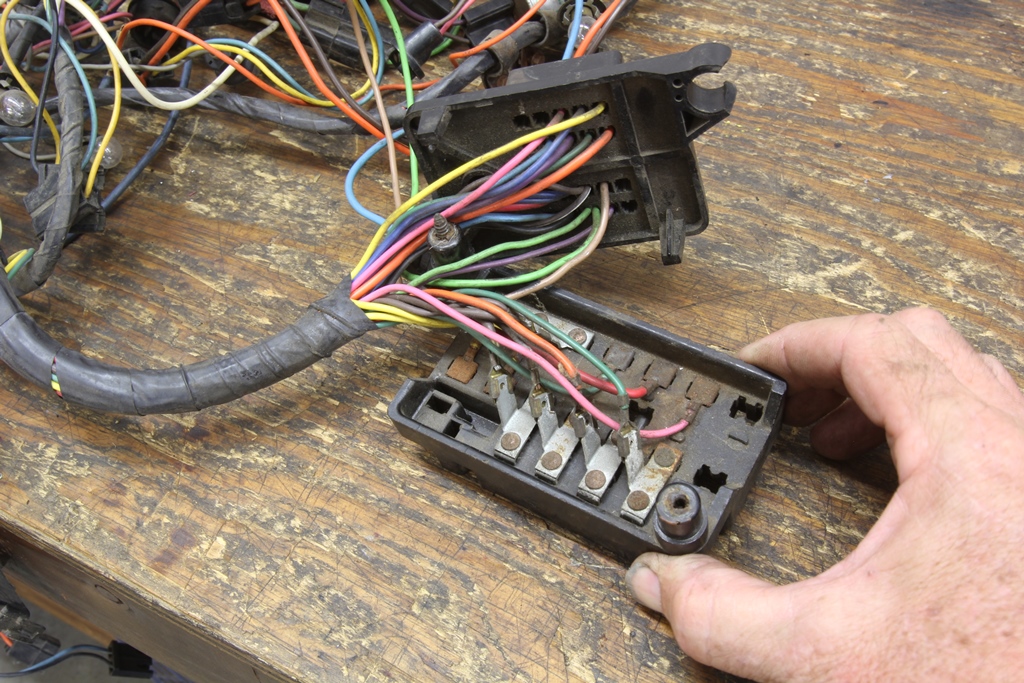

All the 1960s, and even up through the late-‘70s, GM cars used a fuse box with glass fuses. The snap-in connectors for the fuses, as well as the connections inside the fuse box, were just tinned sheetmetal. The problem occurs when these connections begin to deteriorate with rust which is accelerated based on how badly these cars leaked into the interior in the rain.

Over the years, if the car leaked, the interior would experience high humidity levels causing those sheetmetal connectors to rust. Multiply this over 50 years and you have a fuse box full of rusty connections.

The GM fuse boxes bolt together at the firewall with the power feed coming from the battery/alternator connection. This live battery wire enters the fuse box with something as simple as a female blade connector over a male terminal. Once the corrosion starts, vibrations can cause intermittent disconnect. When that happens, it’s like disconnecting the entire electrical system from the car. Power is lost to the ignition key and to the entire interior. So if you are driving at night, the engine will die, then all the lights fail, which is generally disconcerting.

The solution is pretty easy and should be obvious to you now.

If the fuse box has otherwise not been abused or tampered with, you can disconnect the battery, go under the dash on the driver’s side and find the fuse box. Look for a couple of sheet metal screws that attach the fuse box to the firewall. Remove these as they connect the two halves of the fuse box together. (There might be slight differences in the design as I’m operating from my experience with Chevelle and Camaro fuse boxes from that same time period.)

You should be able to access one half of the box from the interior. Find the main power feed—it should be the largest wire feeding into the fuse box. Clean all the rust from that terminal, and while you’re in there, the other connectors as well. A Dremel tool with a wire brush attachment works well. It would be wise to clean all of the connections that look corroded. Before you re-assemble this, place a small amount of oil on each terminal—this will keep the connections from corroding again—at least for the near future. After re-assembling the fuse box you can reconnect the battery and check to make sure everything electrical still works—assuming it worked in the first place.

The more expensive but ultimately more permanent technique is to just replace the entire under-dash harness. Several companies make these harnesses including American Autowire. Summit Racing carries a complete American Autowire under-dash harness that includes a new fuse box that uses later model blade fuses. This harness is a bit more expensive than just fixing the rusty connectors, but it’s likely this new harness will promote all the electrical devices to run more efficiently because of less voltage loss due to poor connections. Remember, your harness is essentially 50 years old and likely very tired.

Either process will cure your intermittent problem.

This is not just a problem with GM cars. I remember a ‘64 Lincoln Continental that my dad owned. He was a Marine Corps pilot from the ‘60s, and when the car would suffer this same problem on the freeway, he would call it a “low-altitude emergency.”

His solution was to give the fuse box a swift kick and often that would re-connect the electrical connection. It’s crude, but it works!

I have a 5:02 with the fast fuel injection system in it it ran great for a year-and-a-half and then I developed a misfire and finding out that the cap was no good I replaced the cap and now I’m having trouble programming the computer because the car will only run 5 to 10 seconds at a time and I was wondering if you had that issue and it does have to do with spark because I’ve tested this Bach and it shuts the coil off and it distributor off and MSD box

My ZZ 502 had a simular issue, turned out dist. gear was going south. Easy repair and appx. 40 bucks for part at dealer

I had a 68 Corvette 427 that would completely go dead on occasion, only the horn would work. After some investigation, going the screws in the bulkhead connector had nearly fallen out letting the connection come apart. Tightened it all up and never had another problem.

This may sound lame but how do you take the pins out of the fire wall side of the fuse box