There’s no time like the present to get out and enjoy shows, cruise-ins, and races. And by enjoy the races, we mean actually go out and race.

If you’ve never gone racing—or if you’ve never fully understood bracket racing—this post is intended to nudge you toward the starting line. Truth is you don’t need a lot of money or special equipment to go bracket racing—all you need is a safe car, a local track, and the desire to learn. This post will teach you the basics of bracket racing—what it is, how a race is run, how a track is set up, and more.

A bracket drag race is a straight-line acceleration contest between two cars (usually starting at different times—more on that in a minute) from a standing start over a specified distance, usually a quarter-mile or an eighth-mile.

Racers line up in front of an electronic countdown device nicknamed a Christmas Tree (or just the Tree). When the cars leave the starting line, electronic timers record how long it takes each one to reach the finish line. This is called elapsed time, or ET for short. That is why bracket racing is also known as ET racing. Top speed is also recorded, but does not determine a winner in a bracket race.

The Track

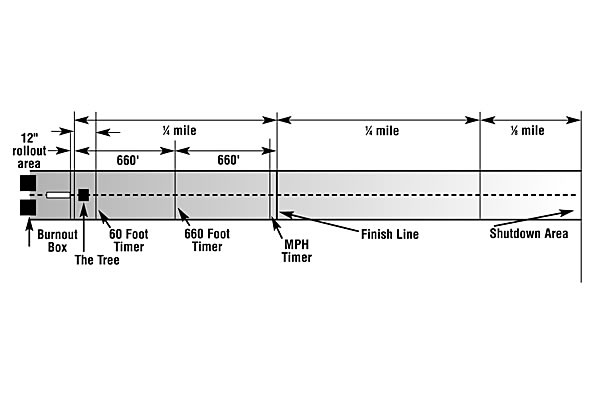

Before we get into the nuts and bolts of an actual race, let’s explore the nuts and bolts of where you’ll be competing—the track. Most tracks are a quarter-mile in length; but there are a good number of eighth-mile tracks too. Refer to Slide #1 in the Slide Show to see where the following areas are located:

Burnout Box—the area just before the starting line that is sprayed down with water so you can do a quick burnout to warm up the tires or slicks for better traction and get rid of any debris lodged in them.

60-Foot Timer—Measures the time it takes the car to cross the first 60 feet of the track. This shows you how well the car launches, which affects your elapsed times.

660-Foot Timer—Measures elapsed time at the halfway point of a quarter-mile track. At some tracks, speed (in miles per hour) is also recorded. Some tracks also have timers at 330 and 1,000 foot intervals.

Mile-Per-Hour Timer—Also known as the speed line, this timer is located 66 feet before the finish line. It records the car’s average speed between it and the finish line. This is the mile per hour figure on your time slip.

Finish Line—When you cross the light beam at the end of the quarter-mile, you stop the ET clock. The amount of time (in seconds) between when the timer was activated and when it stopped is the ET figure on the time slip.

Shutdown Area—The area past the finish line, usually a quarter-mile or more in length, where you can safely slow the car down to take the turnout to the time slip booth. If something goes wrong and you can’t stop the car, most tracks have a sand trap, net, or other setup at the end of the shutdown to stop you.

The Tree

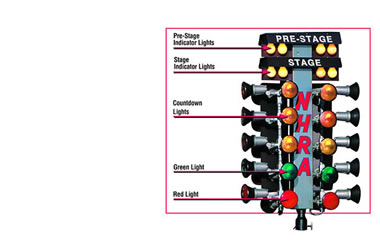

A drag race starts in front of the Christmas Tree. In simple terms, the Tree is a set of vertical lights that gives the driver a visual countdown to the start of a race. The lights are as follows from top (see Slide #2 in the Slide Show for a visual reference):

Pre-Stage Indicator Lights—Yellow bulbs that indicate that you are close to the starting line and should be ready to stage.

Stage Indicator Lights—Second set of yellow bulbs that indicate you are fully staged and ready to race. The bulbs are triggered when the front wheels cross a beam of light from a set of photo cells. These cells trigger the timer when the car leaves the light beam.

Countdown Lights—Amber floodlights that count down to the green light. There are two types of countdowns, or starts. The .500 or Full Tree start used in bracket racing flashes one light at a time, with a .500-second difference between the last amber light and the green light. The .400 or Pro Tree for heads-up and professional classes flashes all three lights simultaneously with a .400 second difference between the amber and green lights. Typically, you want to leave when you see amber—the top bulb, middle, or last, depending on your car or class.

Green Light—This is the one you’re waiting for. When it flashes, it means you’re late if you’re not moving yet! This point of the run is called the launch.

Red Light—This light will flash if you break the stage beam before the green light is activated. Known as redlighting, this action automatically disqualifies you and gives the win to your opponent.

This brings us to reaction time, which is how quickly a racer can get off the starting line when the light goes green. Better known as cutting a light, a quick reaction time will give you a big advantage over your opponent, especially if you are running the slower car. The starting line is where most bracket races are won or lost, so time practicing your staging and launching techniques is time well spent.

Running a Bracket Race

Before a bracket race can start, each car must determine what time to “dial.” To figure out an accuate dial, a racer needs to use time trials to determine the elapsed time they think their car will run.

Beginning racers usually base their dial-ins on a few passes down the track. For veteran racers, a dial-in is serious business, based on years of experience and countless runs. A good bracket racer can hit on or very close to their dial-in almost every time.

When two cars are matched up for a race, the dial-ins are compared; the slower car is given a handicap, or a head start equal to the difference between the dial-ins. To win, you need to run closer to your dial-in than the other guy. There are three winning scenarios:

- Run as close to your dial-in as possible without going quicker, or breaking out

- If both cars run faster than their dial-ins (called running under or breaking out), the racer closest to their dial-in wins

The Time Slip

After you make a run, the guys in the little booth at the end of the track will hand you a piece of paper with numbers all over it. This is the time slip. It provides a wealth of information about your pass—how well you launched, how quick and fast you went at various points on the track, and your elapsed time and top speed. If you were running against an opponent, the time slip tells you how they did, too.

The sample quarter-mile time slip in Slide #3 in the Slide Show illustrates the following terms:

Lane—Shows which lane you are in

Car Number—Most cars are assigned numbers at official races

Class—Marked if running in an official race. Not used for test and tune sessions

Dial-In—The elapsed time you predicted your car would run

Reaction Time—How quickly you reacted to the green light on the Christmas Tree. In the sample time slip the Tree was set for a Sportsman (.500 second) start

60′, 330′, 1/8, MPH, and 1,000 Foot Times—These figures are the elapsed times measured at the 60, 330, eighth-mile (660 feet), and 1,000 foot marks. The MPH number is measured at the 660 foot mark

Quarter-Mile ET and MPH—These are your final elapsed time and top speed numbers—the ones that count!

How Do I Start?

Now that you have an idea on how bracket racing works, take a trip to your local track—and just watch. Pay attention to how the cars launch, how the Christmas Tree works, and what racers do in the pit area. Most importantly, ask questions. There isn’t a racer we know of who doesn’t love to talk about their car and how they approach a race. Most racers will be happy to give you pointers on improving your technique—and that will teach you volumes on how to race.

After spending time watching bracket racers at work, it’s time to get your feet wet. A great way to do that is at a “test and tune” session at your local track. For a small fee, you can practice your starting line procedure, learn how the car reacts to tuning changes, and make passes down the track without the pressure of racing against someone. Chances are there is a drag strip within a couple hours’ drive. Most tracks are sanctioned by the National Hot Rod Association (NHRA) or the International Hot Rod Association (IHRA); you can locate a track near you by visiting their websites.

We hope this primer helps you understand the basics of bracket racing. One thing we will guarantee: once you make that first run down the track, you’ll be hooked for life!

Thanks for the explanation.

[…] and chat with fellow enthusiasts. It’s grassroots hot rodding at its best. The same goes for bracket racing at the local […]

great help nice and simple.

For some of my friends that are new to bracket racing. Here is a brief explanation of what is going on. So the next time you come down to Beacon Dragway, you will have a better understanding of the race.

[…] taught you the basics of bracket racing in a previous post. Now, we’re going to give you the next lesson—how to […]

You forgot to remind us how much fun it can be!!!!

What purpose does it serve to have a head start equal to the difference between the dial-ins, since winner is based on ET and dial-in?

So reaction time has no effect on bracket racing?

What am I missing here?

Bracket racing is all about having the best package. This write up is a very vague intro to bracket racing. Example: you dial 7.00 seconds and run 7.005 with a .520 light with .500 being perfect you have a .025 package. I however dial 6.00 seconds and run 6.002 with a .518 light I have a better .020 package and take the win by .005. Hope this helps.

If you dial 6.00 and run 5.992 based on a .518 light you now have .010 package. Do you still win? Or are you not allowed to go faster than your dial in period?

Reaction time is one of the factors that determines whether you win or lose. This is the elapsed time from when the light turns green and the time you leave the starting line. Not the same thing as the elapsed time from the starting line to the finish line. A car making a 10 second run can waste 2 seconds sitting on the starting line after the light turns green and a 11 second car that leaves the starting line at the moment his light turns green will beat it to the finish line by 2 seconds.

[…] Before a race, the driver of each car is required to estimate the time it will take to reach the finish line. This is known as the “elapsed time”, or “E.T.” for short (bracket racing is also sometimes known as “E.T. racing”). Estimating the time is called “dialing in”. […]

So if you are only try to get close to your dial, in theory you can just put in like 1 minute and then creep down the track with a watch and make sure you hit exactly 1 minute and then win. Why do cars have to be fast if you are only try to get your dial ??? Do I miss something. ??

NeRly all tracks. Limit the slowest cars to 25 seconds. In the 1/4 mile. So as not to delay the days events and so the the faster car that you maybe racing. Is not forced to wait. An ex ordinary amount possibly causing that car to over heat or experience other mechanical issues. As in early posts. Your over all reaction to the lights and how close you predicted the car to run plays into the whole race. Some tracks use .000. Others use .500 as a perfect light. Depends on the computer programs that track uses. .000 is easier to understand. For new racers. The closer to a perfect light. And the closer to your ET. The better chance of you winning the race. The further from perfect or a slower reaction and the less accurate to predict the ET. The less chance you have of winning. If your new to a class or new to a track. You may not know many people there and won’t lnow how those same people may drive and react to the track conditions. Making your. Predictions even more critical. But as a new racer it is best to talk with the staff and get help to understand. The how to and why’s. Plus bend the ears of the locals. We live to share our knowledge and experience. To help you become successful and enjoy the sport more.

I find NHRA bracket racing defeats the purpose of racing. what is the point when there is so much aftermarket equipment available these days, cars should be allowed to run heads up. NHRA could try an experimental heads up class like the old days when racing meant something and was easier to understand and watch. (Cost less to without all the electronic nonsense) I remember watching Scotto Bros max wedge fury running a thunderbolt in finals of a big race in 1972 on LI, they ran heads up and the finish was so close the electric timers called out the winner, very exciting,stands were packed.

I agree. I remember when bracket racing first got started back in the early 70s. It just ruined drag racing for many people. Again and again we saw somebody run an honest race and win, and then get disqualified because he ran .00000001 mph past his “dial in.” Or we’d see a Volkswagen getting a 10 second head start on a 426 Hemi Cuda. It was as exciting as watching paint dry.

I believe the intent was to attract low budget street racers to the sport. But it does take away some of the “racing” away. Personally, I think they should just run different class by the whole secs. and let the chips fall. 11.00, 10.00, 9.00….just pick where your vehicle runs and don’t break out. This way if you have a 9.90 car you can tinker and tune to go for 9.00. keeps the competition and tuner end going. A friend of mine back in the day spent crazy money on a track car and occasionally he won events. Later on after marriage, a house….he raced a old monte carlo, totally stock piece of shite. He then won almost every week end. All the motorheads hated him, but he learned his lesson, you don’t need a fast car to win bracket racing. the car was very consistent, all he did was mash the gas pedal. car never behaved badly, never spun, automatic tranny shifted perfectly every time. The epitome of consistency.

[…] Before a race, the driver of each car is required to estimate the time it will take to reach the finish line. This is known as the “elapsed time”, or “E.T.” for short (bracket racing is also sometimes known as “E.T. racing”). Estimating the time is called “dialing in”. […]

You may want to do an update on the top bulbs as more and more tracks are doing the blue LED half round bulbs. My advice to anyone starting out is to check your ego at the gate. Your car has nothing to prove but you need to train yourself on launching and dial in.

For the love of God, what is the difference between bracket 1, bracket 2, bracket 3

[…] A good bracket racer can hit on or very close to their dial-in almost every time. When two cars are matched up for a race, the dial-ins are compared; the slower car is given a handicap, or a head start equal to the difference between the dial-ins. To win, you need to run closer to your dial-in than the other guy.[8] […]

I quit racing when the engine build, tune up, Supension and driver skill all when out the window. I’m not spending big bucks to go fast or faster than some meathead with a stock 15 sec car. Brace racing took the competiveness out of the sport and put the starting line as the competition.

lets talk about sandbagging? Which is driving out of the class you are supposed to be in ( because your not good enough) so you can beat slower cars! This is ridiculous. I had a super pro race against my pro class. He was even allowed to put a super pro dial in ! Now is that cheating and taking the fun out of it, OH YES.