I’ll tell you right up front—I’m a diehard Ford enthusiast and have been for more than 50 years. That was pretty challenging in high school back in Maryland with a parking lot filled with Chevelles, Camaros, Novas, Impalas, and C10 trucks.

It was the same deal at Capitol Drag Raceway in Maryland where Chevrolet dominated in both time slips and sheer numbers. There was this one guy with a Rally Green 1969 Z28 Camaro sporting a high-revving 302ci small block that ran 11 second ETs on the regular. He’d put that thing in the water box and spin the short-stroke mill to 6,500 RPM. It gave everyone goosebumps. The Camaro left the line with wheels in the air, pulling 7,500 RPM shift points down track. Yeah, it was bad to the bone.

Story Overview

- Chevrolet’s DZ302 V8 was developed for SCCA Trans Am racing and the 1967 Z28 Camaro

- The production DZ302 was factory-rated at 290 horsepower but made closer to 350

- Jeff Latimer of Team Nine Motorsports built a better DZ302 with using modern parts from Trick Flow, COMP Cams, Edelbrock, and Holley

- The 302 was dyno-tested with four different intake manifolds and two Holley Classic HP carburetors

The engine in that Camaro was the product of Chevy’s SCCA Trans Am racing program. Facing stiff competition from Ford, Chrysler, and AMC, Chevy pulled out all the stops to build a powerful engine for the new Z28 Camaro that would be competing for the 1967 Trans Am season. To meet the series’ five-liter limit, Chevy engineers led by Vince Piggins put a three-inch stroke crankshaft from the 283ci V8 in a 327ci block. They stirred in 11:1 compression forged pistons and parts from the 365 horsepower L76 327—Duntov 30-30 solid lifter cam, big-valve fuelie heads, and a high-rise aluminum intake topped with a Holley 780 CFM carburetor. The result: the DZ302.

The production engine was factory-rated at 290 horsepower at 5,800 RPM and 290 lbs.-ft. of torque at 4,500 RPM with a 7,000 RPM rev limit. Chevy lied about the power, of course. The DZ302 made more like 350 horsepower, but was downrated to keep the pesky insurance companies at bay. The race version with a bigger cam and other race-only parts made around 450 horsepower with a single four-barrel carburetor. A potent engine, indeed.

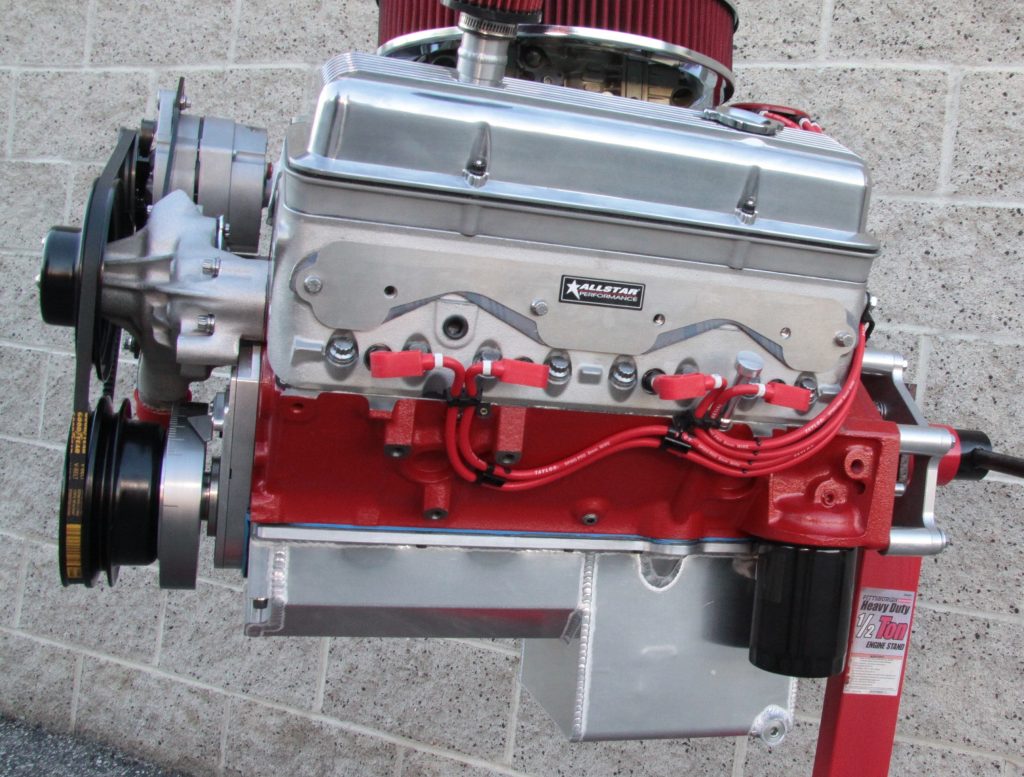

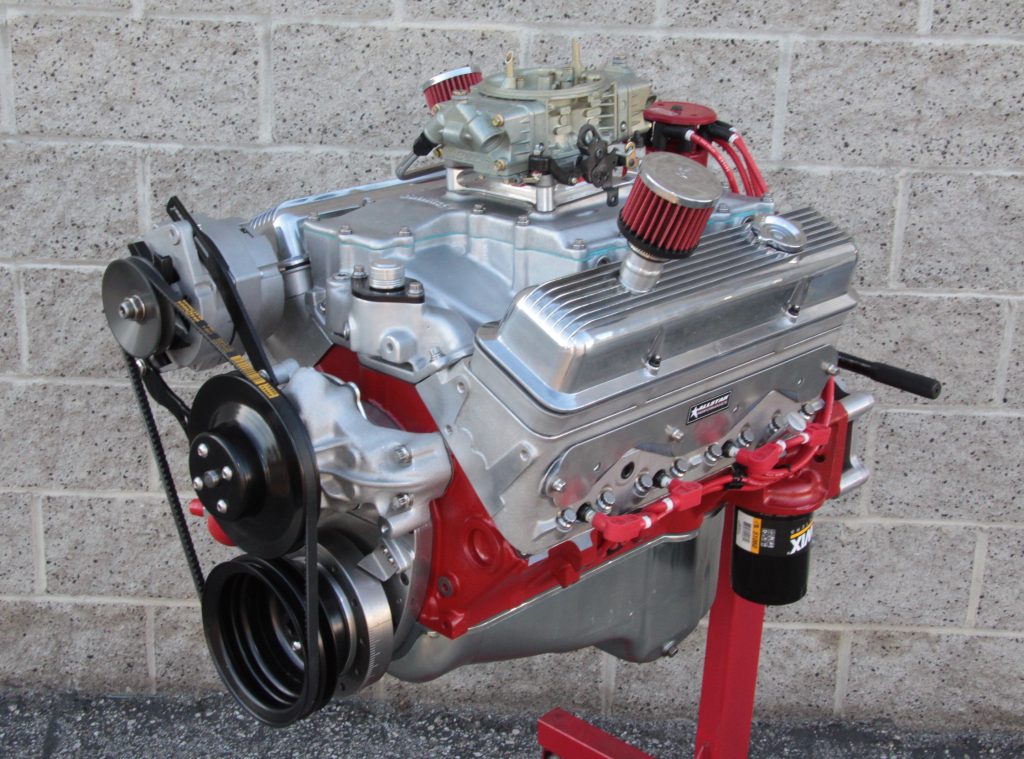

Jeff Latimer of Team Nine Motorsports in Valencia, California, figured he could build a better DZ302 engine than Chevy did using off-the shelf parts. He went to work creating a powerful small block you can build yourself.

Block and Rotating Assembly

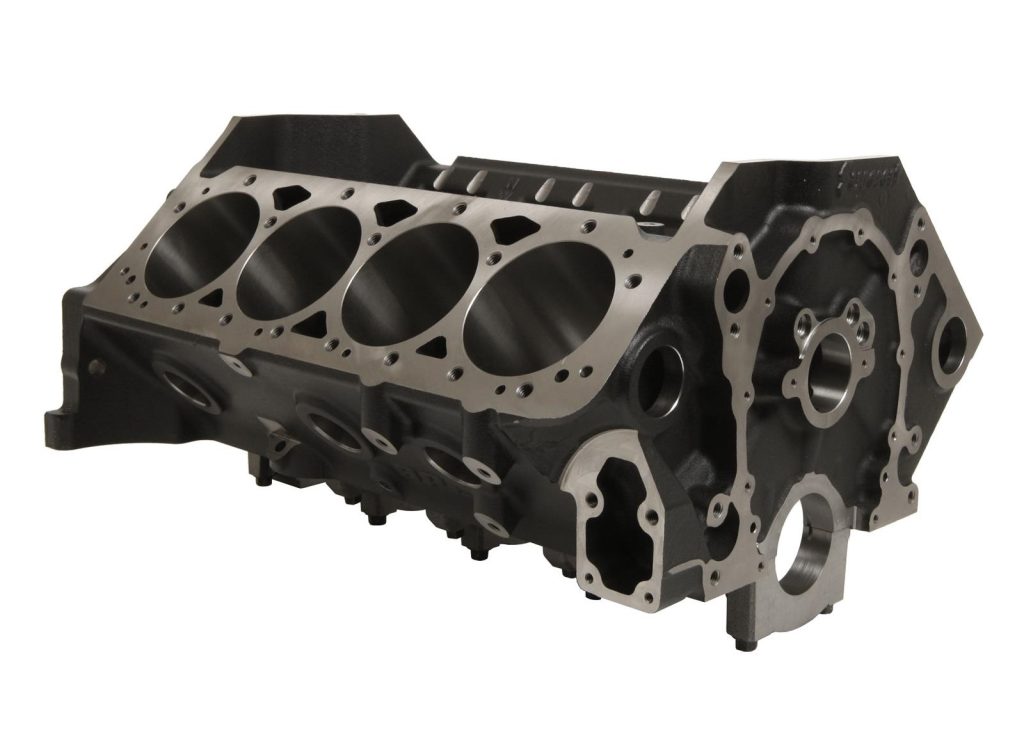

Jeff based the 302 on a Chevrolet Performance Parts 350ci block with a two-piece rear main seal. The block was bored and torque plate-honed to 4.005 inches and fitted with main bearing spacers to accommodate the small-journal steel crank from a 283ci small block.

The Chevrolet Performance block is no longer available. A great alternative is a Summit Racing™ SPC Engine Block. It’s a brand-new, heavy-duty casting that can handle up to 700 horsepower. The blocks are cast in a Tier 1 OEM supplier foundry and precision-finished in the USA on high-speed machining centers. You won’t find a higher quality iron block.

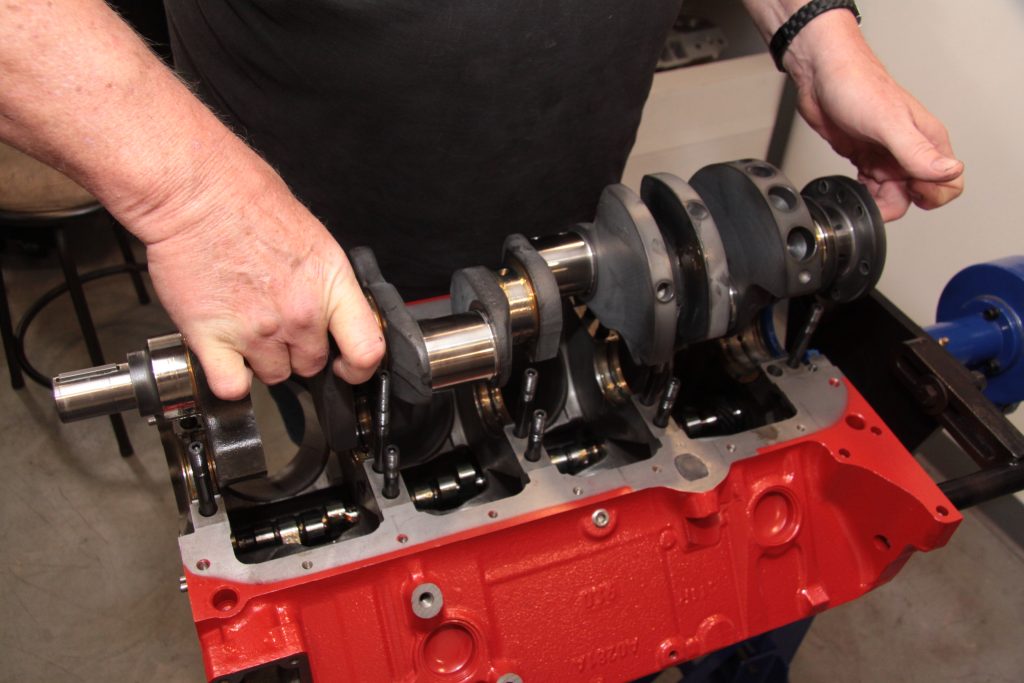

Jeff had QMP Racing Engines in Chatworth, California, align-hone the main journals to get the saddles perfect. Marine Crankshafts in Santa Ana, California, ground the 283 crank to size before nitride-hardening, balancing, and polishing it.

Jeff opted for 6.125-inch long connecting rods to keep the piston compression height short at 1.380 inches. This allowed the use of lighter pistons. The custom Racetec forged pistons sit about .005-inch out of the cylinder bores. The thin 1.5/1.5/3.0mm ring pack helps reduce internal friction.

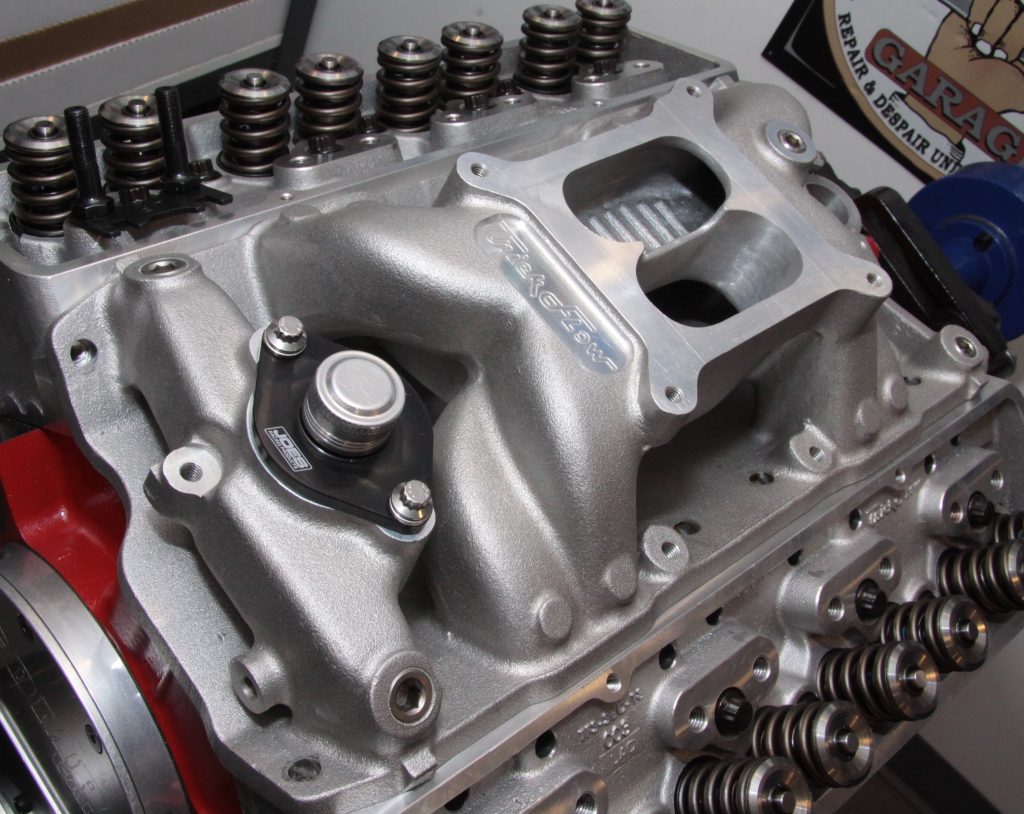

Camshaft and Valvetrain

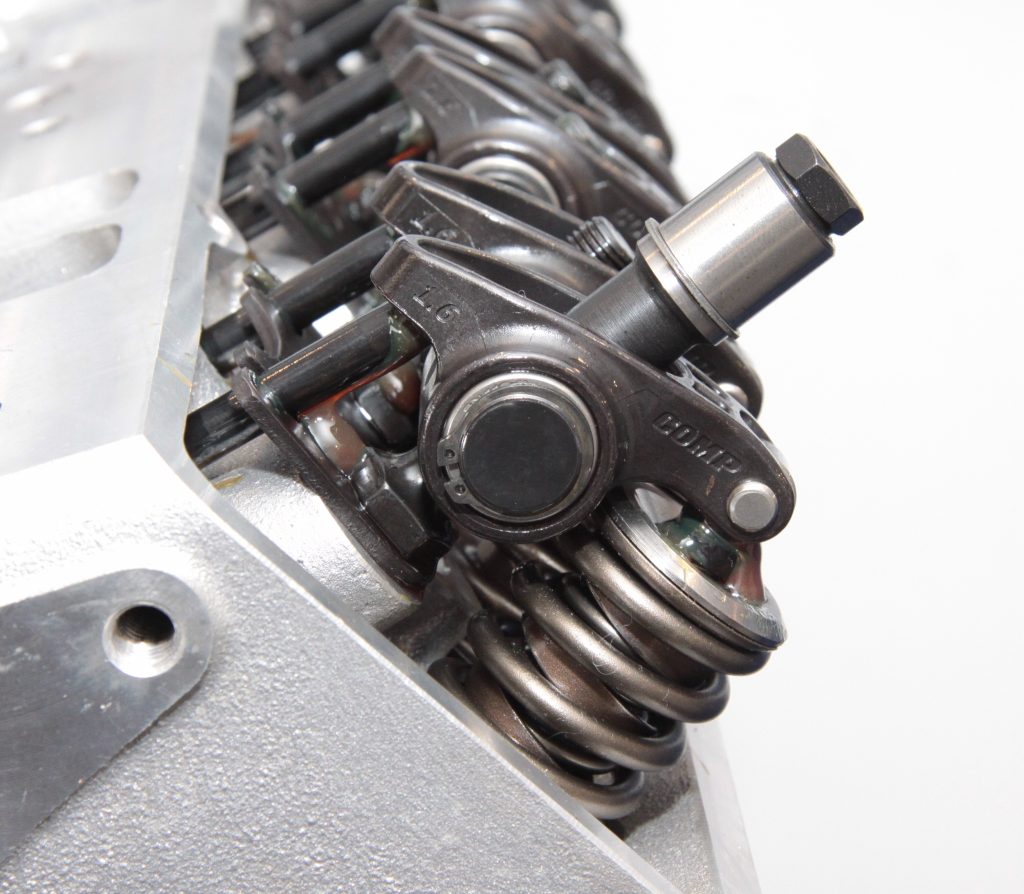

The factory cam specs for the production DZ302 were 254 degrees duration on a 112-degree lobe center and .485-inch lift on the intake and exhaust sides. Jeff opted for a COMP Cams Xtreme Energy solid roller camshaft. Duration and lobe center were similar at 254/260 degrees duration and 110 degrees. But the COMP camshaft offers a ton more lift—.620/.627 inches of it with 1.6 ratio rocker arms.

Jeff added Trick Flow valvetrain stud girdles for stability. The CNC-machined aluminum girdle reduces rocker stud flex for more consistent valvetrain timing and lift at high RPM. You’re going to need valve cover spacers or tall valve covers to clear these girdles.

Other valvetrain upgrades include 1.6 ratio COMP Cams Ultra Pro Magnum roller rocker arms, COMP one-piece pushrods, and ARP rocker arm studs.

Cylinder Heads

Jeff told us the Trick Flow DHC 175 cylinder heads were perfect for this project thanks to their small cross-section intake runners. The as-cast runners increase airflow velocity for good low-to-mid-range torque on the street—something the DZ302 was severely lacking—and have profiles that mimic CNC-machined runners for improved high-RPM horsepower. The combustion chambers are CNC-profiled to promote combustion efficiency and maximize power with less ignition timing. That reduces the potential for detonation.

The DHC 175s are cast from A356-T61 aluminum, but Trick Flow designed them to look a lot like factory ‘camel hump’ iron heads. Some rattle-can Chevy Orange paint and no one would know they’re aluminum.

The Polygraph Room

Jeff took the little 302 to JGM Performance for the dyno testing. He decided to experiment with a variety of intake manifolds to see which performed the best. All were professionally ported for maximum airflow potential:

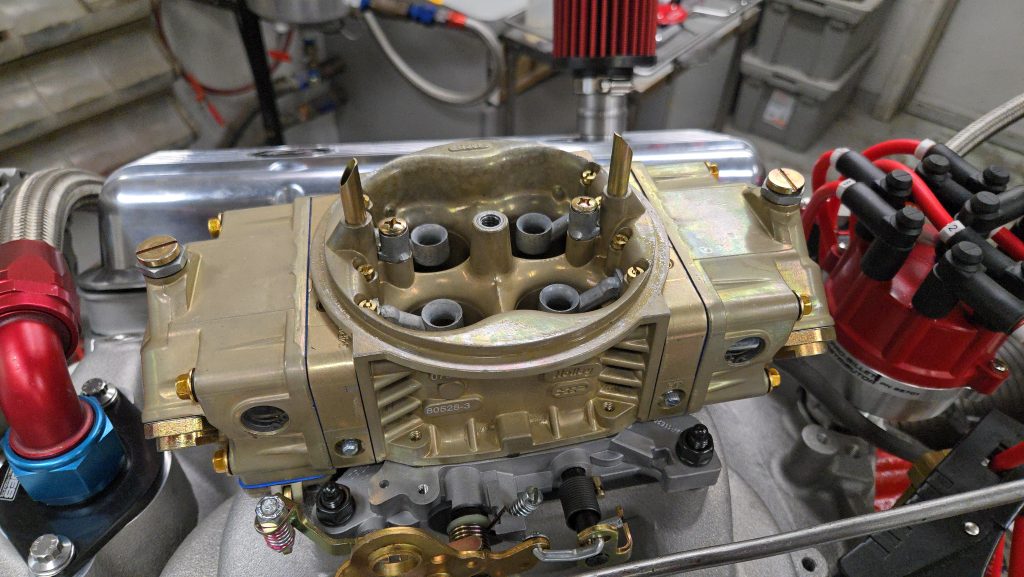

Jeff used a 750 CFM Holley Classic HP carburetor for dyno pulls with the Trick Flow and Edelbrock intakes. He also made pulls with an 830 CFM Holley Classic HP carburetor on the Holley Strip Dominator and Edelbrock Victor Jr. manifolds. Jeff tested the intakes with and without a one-inch tall Canton Racing open carburetor spacer and an HVH Super Sucker combo spacer.

Trick Flow StreetBurner with 750 CFM Holley

The Trick Flow dual plane intake really liked the open carb spacer. The engine made 15 more horsepower and eight lbs.-ft. of additional torque with it. Dyno testing showed it was the best manifold for street use as it made more usable low- and midrange torque.

Pull One, No Spacer

- 449 horsepower at 6,800 RPM

- 380 lbs.-ft. torque at 5,300 RPM

Pull Two with Open Spacer

- 464 horsepower at 7,400 RPM

- 388 lbs.-ft. torque at 5,400 RPM

Edelbrock Victor Jr.

The 302 with the Victor Jr. made 16 more peak horsepower and 13 lbs.-ft. less torque that it did with the StreetBurner. That’s common when switching from a dual plane to a single plane intake. The combination of the 750 Holley and the Super Sucker carb spacer lost four horsepower, indicating the carburetor was a wee bit too small for the extra plenum volume. Adding the 830 Holley brought back six horsepower but gave up six lbs.-ft. of torque.

Pull 1, Holley 750 HP, No Spacer

- 480 horsepower at 7,500 RPM

- 375 lbs.-ft. torque at 5,600 RPM

Pull 2, Holley 750 HP with Super Sucker Spacer

- 476 horsepower at 7,400 RPM

- 375 lbs.-ft. torque at 5,500 RPM

Pull 3, Holley 830 HP with Super Sucker Spacer

- 482 horsepower at 7,500 RPM

- 371 lbs.-ft. torque at 6,200 RPM

Holley Strip Dominator

The Strip Dominator manifold is very similar to the Edelbrock Victor Jr., so the dyno numbers were close as well. The Super Sucker carburetor spacer cost four horsepower and one lbs.-ft. of torque.

Pull One, Holley 830 HP, No Spacer

- 482 horsepower at 7,500 RPM

- 372 lbs.-ft. torque at 5,700 RPM

Pull Two, Holley 830 HP with Super Sucker Spacer

- 478 horsepower at 7.500 RPM

- 371 lbs.-ft. torque at 5,600 RPM

Enter the Smokey Ram

Just for fun, Jeff wanted to run Edelbrock’s classic “Smokey Ram” intake manifold (#2850 SY-1). It was similar to the cross-ram style dual quad manifold Chevy developed for the Trans Am program. When the SCCA changed the rules and dictated a single four-barrel carburetor for the 1970 season, Chevy switched to a high-rise single four-barrel intake.

The cross-ram design was nothing more than a tunnel ram on its side, Jeff explained. “The main difference is plenum volume. The Smokey Ram has longer intake runners to improve low-end torque, something the little 302 engine really needs.”

Jeff found a Smokey Ram in Southern California, but it needed a lot of work. He took it to Chris Brintnell for modifications and port work. Plates were fabricated and radius work was done at the corners to improve airflow. The mating surfaces between the intake base and the intake lid were machined perfectly flat surface for improved sealing.

The Smokey Ram was tested with the 830 CFM Holley HP carburetor and the two carburetor spacers. The manifold fell well short of the Victor Jr. and Strip Dominator in terms of peak horsepower, and delivered comparable horsepower and torque numbers to the Trick Flow StreetBurner, albeit at higher RPM.

The dyno results were exactly what we expected,” Jeff said. “We knew the Smokey Ram would produce close to the best torque numbers, yet would not make as much horsepower as a modern single plane intake.”

Pull One with Super Sucker Spacer

- 461 horsepower at 7,400 RPM

- 387 lbs.-ft. torque at 5,300 RPM

Pull Two with Open Spacer

- 459 horsepower at 7,400 RPM

- 388 lbs.-ft. torque at 5,400 RPM

Pull Three with Open Spacer and Water Pump/Alternator Drive Belt Removed

- 464 horsepower at 7,400 RPM

- 390 lbs.-ft. torque at 5,400 RPM

Reaching for 500

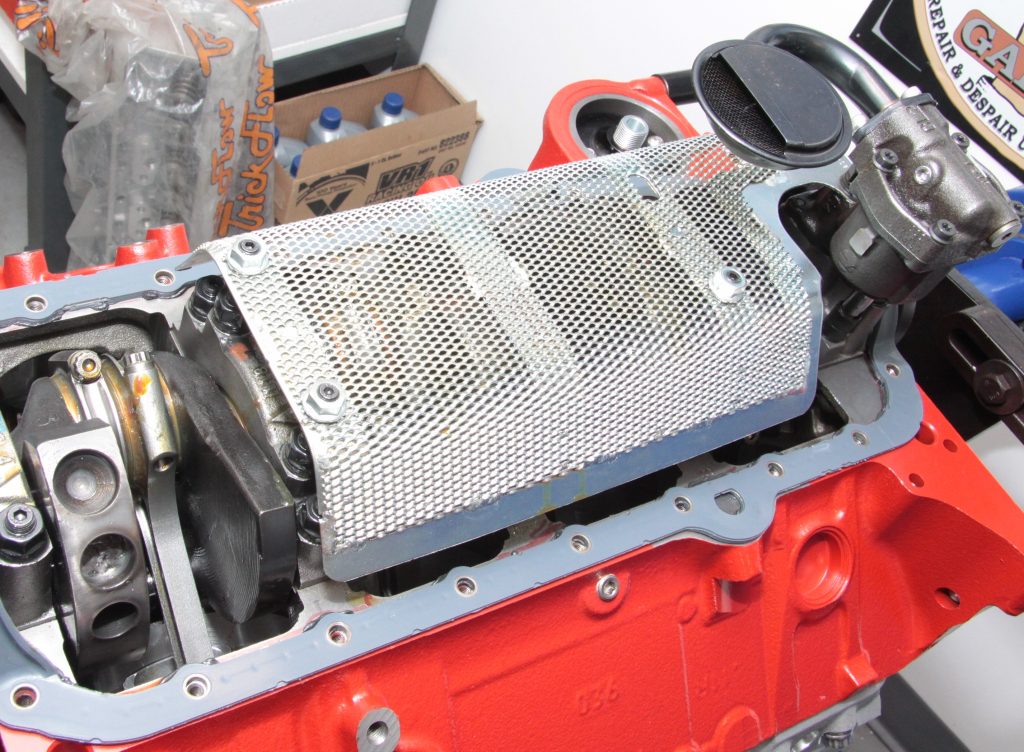

After reviewing all of the test data, Jeff wanted to make one more set of dyno pulls to see if the 302 could make 500 horsepower. He decided the Victor Jr. single-plane manifold and the Holley 830 HP carburetor would be the best combination. Jeff also removed the Holley mechanical fuel pump and tried a Steph’s aluminum drag race pan with a right-hand side kickout for better oil control.

Pull One, No Spacer

- 487 horsepower at 7,400 RPM

- 387 lbs.-ft. torque at 5,500 RPM

Pull Two with Super Sucker Spacer

- 490 Horsepower at 7,500 RPM

- 388 lbs.-ft. torque at 5,900 RPM

Despite Jeff’s best efforts, the 302 missed the 500 horsepower mark by 10 ponies. The engine made 1.62 horsepower per cubic inch of displacement, which is pretty darn good, but will need to make 1.65 horsepower per cubic inch to hit 500. As a man on a mission, Jeff plans on revisiting the engine combination and return to the dyno.

One upgrade he thinks will help greatly are a pair of Trick Flow DHC 200 cylinder heads. Not available when he built the 302, Jeff explained the heads’ bigger CNC-ported 200cc intake runners and 64cc CNC-profiled combustion chambers with 2.055-inch intake valves will definitely improve high-RPM power and help make 500-plus horsepower. For now, let’s see how he built our Trans-Am Tribute Chevy 302.

Comments