Look inside the average enthusiast tool box and you’ll find they all have something in common—box end and combination wrenches.

They’re the backbone of a good tool collection, because the basic box end wrench (or the box end part of a combination wrench) is the perfect tool for tightening and loosening nuts and bolts. Compared to an open end wrench, the box end wrench is obviously engineered to grasp the nut or head of the bolt on all sides. That way, there’s little or no chance for the wrench to slip. It also means you apply more force to the wrench to loosen or tighten a given fastener.

The basics for a box end are simple: The opening for the nut or bolt head in a box end wrench differs from that of the open end wrench in that its closed. Due to the closed opening, it’s necessary to slip the end of the wrench over the nut or the head of the bolt. In contrast, an open end wrench can slide from the side (at least in most instances).

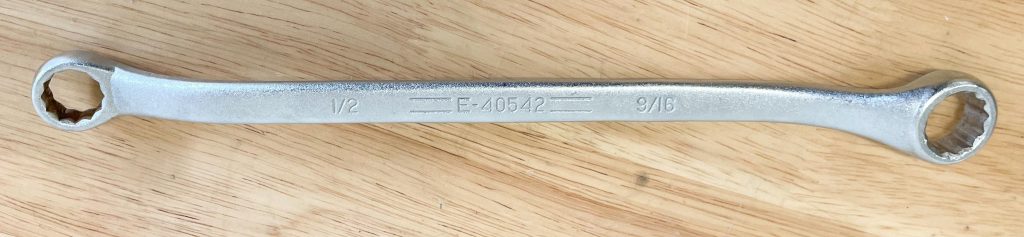

The machined edges (AKA “points”) that surround the interior of the opening in a box end grip the bolthead or nut securely. But they’re not 100 percent tight. Typically, the opening in the head of the wrench is 0.005 to 0.150 inch larger than the size stamped or engraved on the wrench. This is what allows it to slip over the nut or bolt with little effort. And different manufacturers have different takes on the design of the points. Keep in mind the size of the wrench actually refers to the distance across the flats of the nut or the head of a bolt it is designed to tighten or loosen.

You’ll often find that wrenches of smaller sizes (with smaller openings) are shorter in length than wrenches with large openings. This isn’t cast in stone however. There are definitely some exceptions and we’ll get into that further down this article. Tool manufacturers will tell you that the length of the wrench versus the wrench size is established so that you can apply a reasonable amount of torque to the fastener. Basically, they don’t want to be responsible for shearing off fasteners from excessive torque.

On a similar note, it’s not really a good idea to apply additional leverage on the wrench by using a piece of pipe as an extension. It’s also not good idea to use a hammer on the end of a wrench to loosen a fastener.

But most of us do both of these “wrongs” anyway!

The reason tool companies warn you to refrain from these practices is because it can crack, bend, or break wrenches. The additional leverage can also round corners on nuts or bolts, excessively stretch the fastener or break it outright (there are wrenches designed specifically to be struck, but that’s another story).

The box end wrench is offered in either six point opening or a 12 point configurations, with the 12 point being the most common by far. The 12 point is perfect for general use along with work in cramped quarters. Here, the configuration allows the fastener to be turned though an arc of only 15 degrees through half a turn before it is necessary to reposition the wrench for another swing. The 12 points of a box end wrench exert pressure on the six points of a nut or bolt head instead of just two points when compared to an open end wrench. For stubborn jobs or on damaged nuts or boltheads though, the six point box end wrench is the best choice (but again, these tools aren’t as common as 12 point examples). The six point wrench grips the nut or bolthead across each flat, thereby reducing slippage to a bare minimum.

The offset of the wrench refers to the angle between the head of the wrench and its handle. The purpose of offset wrenches is to gain greater access to recessed bolts or nuts and to provide greater hand clearance. Single offset means a single bend or angle exists between the head of the wrench and its handle. On the other hand, a double offset means a wrench has two bends or angles between its head and handle. The standard angle of the single offset wrench is approximately 10 degrees while the double offset angles are approximately 45 degrees,

Everything that applies to box end wrenches applies to combination wrenches. Obviously, this is a convenient type of wrench to have in your collection. It has the speed of the open end wrench for running down a nut or bolt and the strength of a box-end wrench for completely tightening a nut or bolt.

Open end wrenches typically perform the best when placed squarely on the nut or the head of the bolt and pulled toward you. If you look at an open end wrench, you’ll see there’s a long and a short side at the opening. In order to exert less strain on the nut or bolt, try to make it a practice to place the wrench (on the fastener) so that the long side of the opening moves in the direction of the force being applied. In addition, by pulling the wrench instead of pushing on the it you can usually avoid skinning your knuckles if the wrench slips.

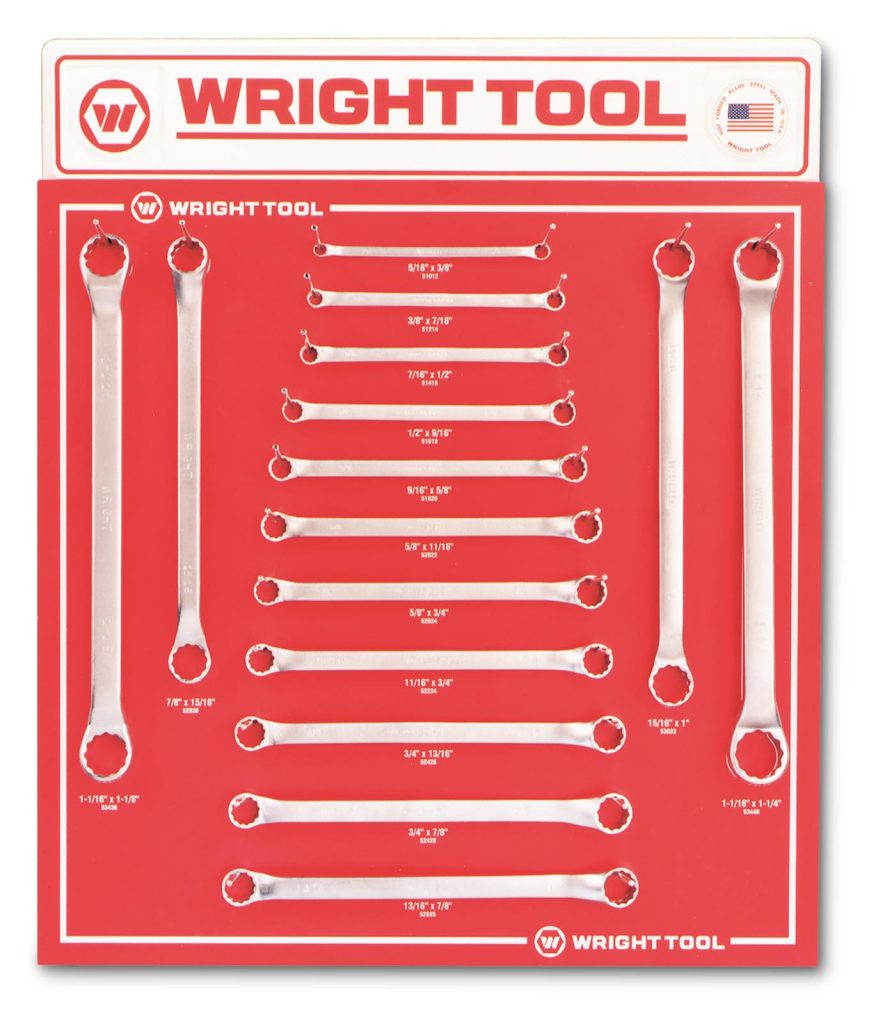

For the sake of convenience, box end and combination wrenches are available in different lengths. These different lengths are sometimes referred to as dwarf (or stubby), midget, standard or extra-long. The idea behind the different specialty lengths is to allow you to gain access to those hard-to-reach fasteners. An example is where you have little room for a wrench and even less room for wrench swing. That’s where the stubby comes into play. Obviously if you’re using an extra-long box end or combination wrench, take some care when the fastener. Given the extra handle length, it’s not difficult to overtighten the bolt or nut.

We took a closer look at the pros and cons of different length sockets and wrenches here.

One other specialized box end wrench is the “angle head”. This is a special purpose wrench made specifically for removing hard-to-get-at fasteners. The most common angle head you’ll find is used to access distributor hold down bolts. Often, angle heads are built for specific jobs for specific makes, models and years of automobiles.

As you can see, there’s a bit more to the common box end or combination wrench than first meets the eye. In the photos that follow, we’ll show you several different examples from the Summit Racing catalog along with examples from the writer’s tool box. Some of these are shiny and near new. Others are ancient and battle scarred, but they still get the job done. By the way, Summit Racing.com carries well over a thousand different box end and combination wrenches and wrench sets. We’ll give you a better look at some wrench designs and options in the pics below.

Comments