I just bought a big-block Chevy pickup from my neighbor who has had the truck for years. He’s been tinkering with it but has finally decided it’s smarter than he is and he sold it to me. The problem is the engine will start and idle, but won’t run anything past a fast idle before it stumbles and dies. We crank it over and eventually it starts but runs through the same problem. The engine is a basically stock 454 with a Performer RPM dual plane intake, a 750 cfm Holley, and headers. Any suggestions? — W.Z.

…

Jeff Smith: There are several things that might cause this issue. It sounds more like a fuel issue than spark so we’ll start on that side of the ledger.

The two things you have to have for an engine to run are fuel and spark. We will infer that the truck has been sitting for a while, so the first thing is to make sure it has gasoline in the tank.

Don’t rely on the fuel gauge. Since you don’t have experience with this truck yet, it may not be accurate. The truck might also be suffering from gasoline that has been in the tank for years. Fuel engineers tell us that gasoline has a planned cradle-to-grave lifespan of roughly six months. If the fuel is two years old or older, consider it worthless except as weed killer. It’s best to drain the old fuel and start fresh.

Begin your diagnosis by checking to ensure there is fuel in the float bowl. Just remove the inspection plug in the side of the float bowl (or look through the sight glass) and jostle the fender to make sure fuel is right near the bottom of the sight hole. If you can’t detect fuel, then perhaps the filter is plugged or the fuel pump isn’t keeping up.

The smart thing would be to replace both if the pump has failed.

If the truck has been sitting for a long time, it’s not unusual for the rubber diaphragm in the pump to go bad. Also make sure it’s that cracked diaphragm is not pumping fuel directly into the oil pan.

Check the oil and smell it to make sure it’s not diluted with fuel. If the oil is diluted, it must be changed before you make any further attempts to start the car.

Next step, pump the throttle linkage on that 750 Holley and see if fuel squirts out of the accelerator pump nozzle. Those nasty additives in pump gas (not the ethanol — we’re talking about aromatics like benzene, toluene, xylene, and others — these are all nasty, dangerous chemicals) will cause the accelerator pump diaphragm to become brittle and frozen.

Operate the throttle and watch to see if the diaphragm actually moves.

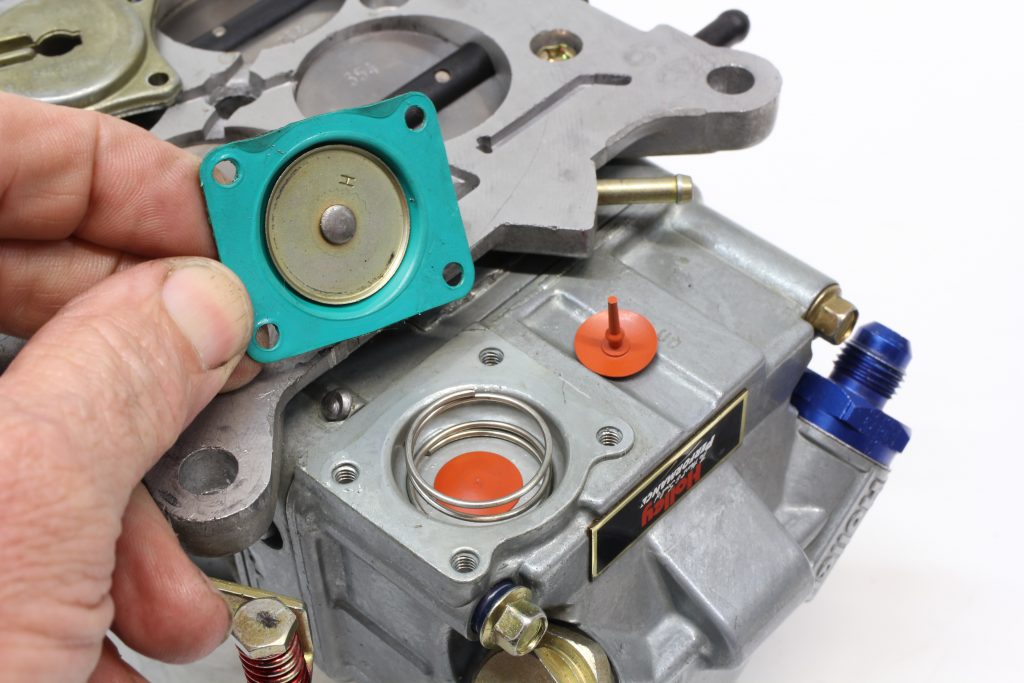

If it’s bad, replace it with one of Holley’s Viton green rubber diaphragms. These are impervious to those bad chemicals in today’s gasoline.

Sometimes the small check valve under the accelerator pump squirter will stick. Remove the squirter and try to lightly pry that needle loose. Don’t just hit the throttle linkage and expect it to float up. It will instead shoot out and may never be found. If you’re really unlucky, it will fall into the intake manifold and you will have to pull the carb to retrieve it.

With any diagnosis, it’s best to eliminate as many variables as possible. We’ve seen loose intake manifold bolts create a situation where the engine won’t stay running because the engine is suffering from a massive vacuum leak. Make sure the bolts are all tight and you might even try spraying carb cleaner around the intake base with the engine running to see if rpm increases. If it does, you’ve identified a vacuum leak.

It’s also possible that the engine won’t stay running because of a plugged main circuit bleed.

There are two air bleeds located on the top of a normal Holley four-barrel carb over each venturi. The outboard bleed is for the idle circuit while the inboard bleed is called the high-speed bleed. Since you say the engine will idle but won’t run beyond idle that could mean that one or more high-speed bleeds are blocked. A blocked high speed bleed could cause running difficulties but this would have to occur in both primary high-speed bleeds, which is unlikely. This will often occur on the idle circuit side and the engine won’t idle properly. The fix is to shoot some carb cleaner down the bleeds and follow that with a blast of high-pressure shop air.

If the carburetor has fuel and all the circuits seem to be functioning properly and the engine sounds like it is idling okay, it might be a good idea to check the initial timing as well as also making sure the advance mechanism is working. Rev the engine and watch the timing mark advance well past the timing tab. This lets you know the advance curve is functioning. Specific numbers aren’t important — it’s enough to know it works. If the timing mark doesn’t move, this reveals the mechanical advance is frozen.

If the timing mark does not move and the vacuum advance is not hooked up, then that tells us the mechanical advance is not working and will need to be addressed. If the timing mark does not move and the vacuum advance is still attached, then both systems are not working and that needs to be addressed. This would not be enough to kill the engine, but it’s worth checking just to eliminate the ignition side as part of the problem.

If fuel delivery is still a problem after installing a new mechanical fuel pump, then it would be worth looking over the entire fuel delivery system. We had a situation once with our ’65 El Camino where the engine didn’t want to run much past a light throttle and we eventually discovered the original factory nylon ‘sock’ over the fuel inlet tube in the tank had collapsed and seriously restricted the fuel pickup.

As a final test, if you have a friend with a known good carburetor you can try, this might point you in the right direction. If the second carb runs fine, then you’ve located the source of your issues. Then you can send your carb out to a rebuilder.

I once had a problem just like yours and chased it for months. Never could get it resolved until I changed the fuel line to stainless. When I removed the old line I found it had been hit with something that had badly crimped it! So there was enough flow to initially fill the fuel bowls but it would not flow enough when it was given throttle to allow the engine to accelerate. Good luck.

There are two air bleeds located on the top of a normal Holley four-barrel carb over each venturi.

All excellent advice for diagnosing your problem, I want to add a situation I’ve come across more than once, and especially on older cabuorated vehicles. If you’re still having a fuel issue after eliminating other possibilities take a minute to crawl under and inspect the fuel lines for any repairs done with rubber hose. If you do come across any splicing with rubber hose, first inspect the hose to see if it is neoprene hose. Fuel line rubber hose is NOT the same as any old hose. The hose is too weak to withstand the suction that goes through it and it will suck closed and starve the motor for fuel, not to mention that gasoline will eat through plain old rubber hose. Do your self a favor and replace any repairs done with rubber hose with neoprene rubber fuel line. If you find this to be the issue, replace fuel line with new metal fuel lines that come pre bent. Good luck and mind you, this is just a thought worth checking out.

Hey Jeff Vincent here I have a 89bbc dully just rebuild my tbi put different manifold both sides pretty much fully tune when I crank it after about 4r5 minutes the engine light comes on when I plug my code reader it code44 lene left side has a new 02 sensor could it be the wrong one any help would be greatly appreciated are sould I drive it for awhile maybe it will clear computer Thanks

I have a 454 stroked to a 496 with a Holley Sniper throttle body. Mild hydraulic roller cam. At about 1500 rpm and light on the throttle the engine has thump. It starts and runs great. The thump is not a skip I don’t think. It’s slight but annoying.

Hmm i like the article and will try this on my 460 ford ! I had it running great but switched to my rear tank one day and all my headaches started ! It has a new distributor and wiring harness to it along with module plugs and wires brand new weiand stealth intake and holley 570 cfm. Carb ! Like i said had it running great until i switched to my rear tank ! Since then ive changed the morain filters on the carb and the inline fuel water separator filter and that helped ! But once it warms up it dies at this point Im going to pull my hair out ! Any help would very much be appreciated

I have a 454 with a Rochester 4bl carburetor occasionally the engine will stall/hesitate, very erratic.Normally engine runs ok.new fuel tank and lines, new distributor and vacuum advance system. Spark plugs recently changed.linkages all lubed. Doesn’t happen all the time? Fuel filters on carburetor and lines all new. Ideas?? Thanks.

I have a 454 in a 92 chevy 1500 rebuilt with mild comp cam comp roller rockers double roller timing chain street fire distributor edelbrock airgap intake with a brawler 750 carb on top everything thing is new it will start but wont idle i have to keep feathering the gas to keep it running as soon as i let off it dies out just cant figure it out

Check for a vacuum leak. If this has been a problem since the engine was rebuilt, check your cam timing. With the adjustable crank gears, people often get the timing marks mixed up. Also check to ensure the timing marks on the timing cover and dampener correctly indicate top dead center. (Any change of these parts can result in inaccurate readings.). Good luck

Brawler carbs are garbage. I bought new brawler and have same problem

I have a roller 454 a 750 summit carb it will crank easy but after you drive it for a while it doesn’t want to crank it spins over good I don’t know if it’s vapor locking or what .I put a msd ignition , electric fuel pump nothing helps like I said it turns over great .

Years ago a co mechanic was pulling his hair of. Similar situation. After trying every thing we could think of we convinced him to pull the tank. We found decorative red wood bark in the tank. It had become semi boyant just enough to gather around the sock/strainer and stop fuel flow,then float back up to let it run again .

1980 454 crate motor it’s in my 69c25 automatic. Everything is good till I drive it. Thought vapor lock. ? It cuts out acts like it’s going to die when driving. Floor it and my eldabrock intake and carb it backfires out the carb. When I’m in park or with the brake on it runs fine when I floor it. No hesitation or backfire. I’ve tried several things . Please help with any suggestions.

This sounds like a sustained load problem that could be ignition related. I would start my measurig fuel pressure to make sure you have good fuel pressure under load. If so, then it’s might not fuel related especially since you say the engine will take a load for a short time like revving it up in Park. Low fuel pressure could also be a partically plugged fuel filer. If fuel system is okay then it sounds like the ignition system is not up to par. it could be the spark plugs are fouled – the ignition will handle a mild load but not sustained. Or, if the ignitin is HEI, replace the module with a quality one – not the ones you find at the auto parts store – those are generally from China and not very good. DUI igniton stuff is pretty good. Also, make sure you have sufficient ignition timing – a good palce is 10-12 degrees initial and that both the mechanicla and vacuum advance are working properly.