For turbo LS folks (actually, any turbo enthusiast), the question is sometimes not just boosted power, but also boost response.

Turbo folks always love the power production, but the only thing better than power is power RIGHT NOW! The surge of torque that accompanies boost is amazing (and unfortunately addictive). Too many turbo combos have succumbed to the notion that if a little boost is good, ALL the boost must be even better. This possibility notwithstanding, boost is still the best way to make more power with any motor, and the mean streets are currently chalk full of junkyard turbo LS builds.

Talk to any turbo owner and chances are good that boost response comes up. Second on the list to absolute power is always response. What do we want? More power? When do we want it? Right now.

While turbo sizing and naturally aspirated torque (low speed specifically) production are the two major contributing factors to boost response, other things can be done to help boost building on your turbo LS.

One area of contention is how the exhaust energy is provided to the turbo, meaning the exhaust manifolds themselves.

Given the need for things like packaging, converter light off (emissions), and longevity, most factory turbo motors rely on cast manifolds. The side benefit of this design is often response rate, but much of this (at the OEM level) comes from the turbo sizing as well.

For aftermarket use, these concerns are less important and this opens up the possibilities for different exhaust manifold designs. For most of us, the two major players are some type of log-style manifold (often created using schedule 40 or similar tubing) and typical tubular headers. The aftermarket is full of header offerings for LS motors, but if going this route, choose them not just for looks or flow, but also for fitment in your chassis.

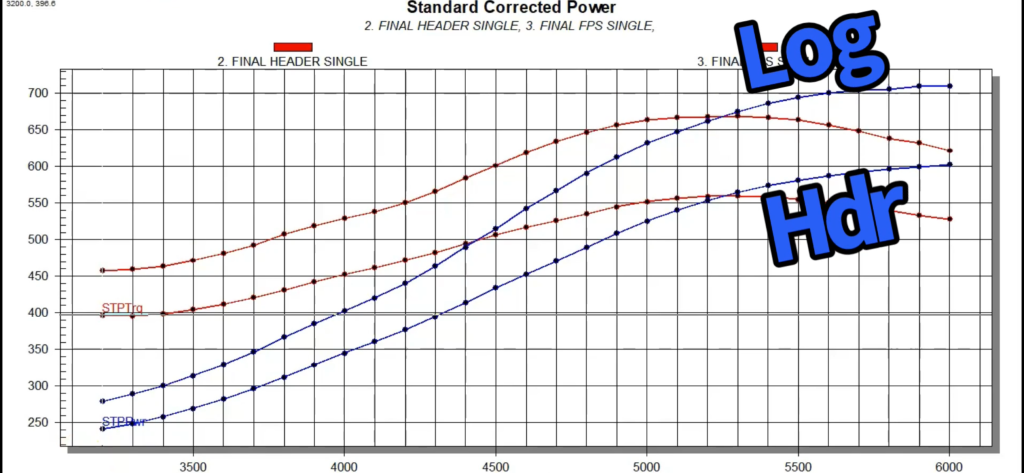

The question then becomes, which one should you choose, is one style really better than the other? While it would be necessary to define “better” here, for our needs, we focused on response rate, meaning which design started making boost sooner. It should be pointed out that this test is something less than a universal header vs log manifold. Different specific designs of each might have different response rates, but here we go (with a curve ball thrown in no less).

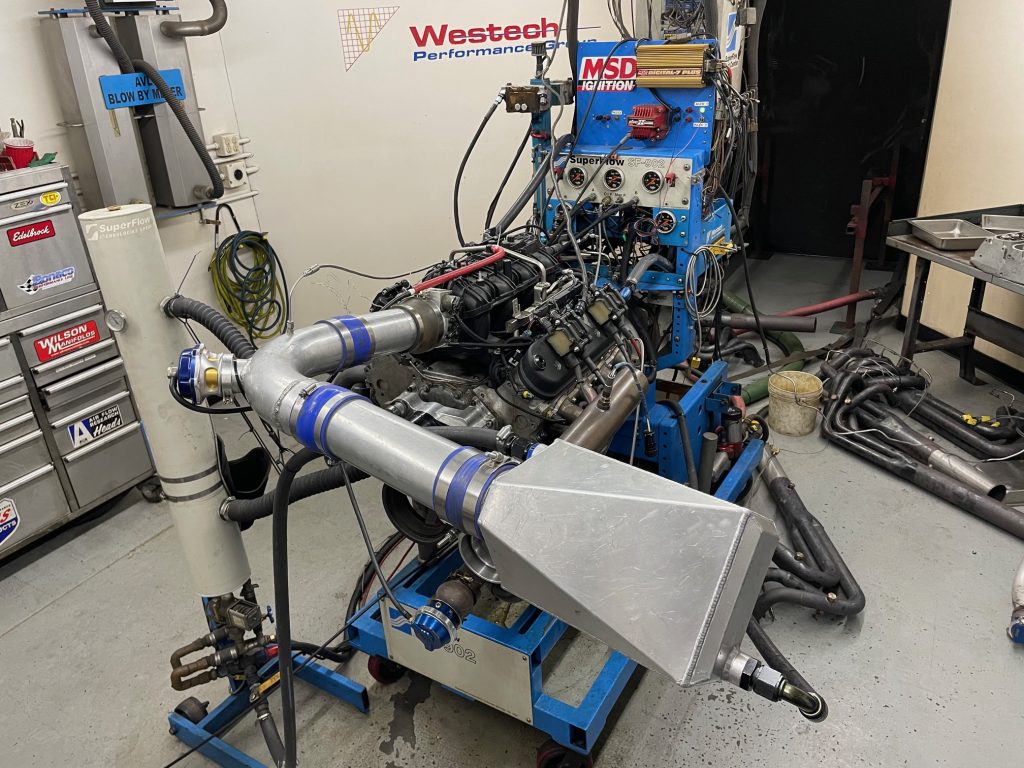

The first hurdle to clear was to devise a test to demonstrate boost response. Sure, we could strap a motor down and run both systems, but the limitations of the engine dyno (stationary load) meant if there was minimal difference between the two with a given size turbo, we might not see much of a difference. Basically, we needed the manifolds themselves to have a bigger stake in response rate.

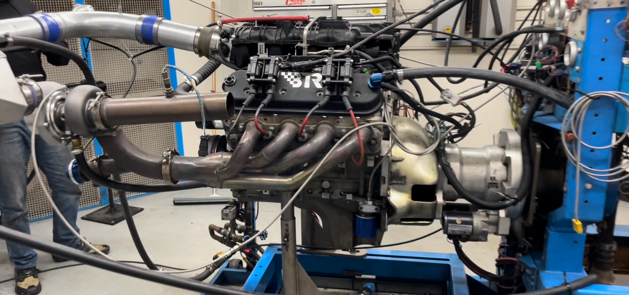

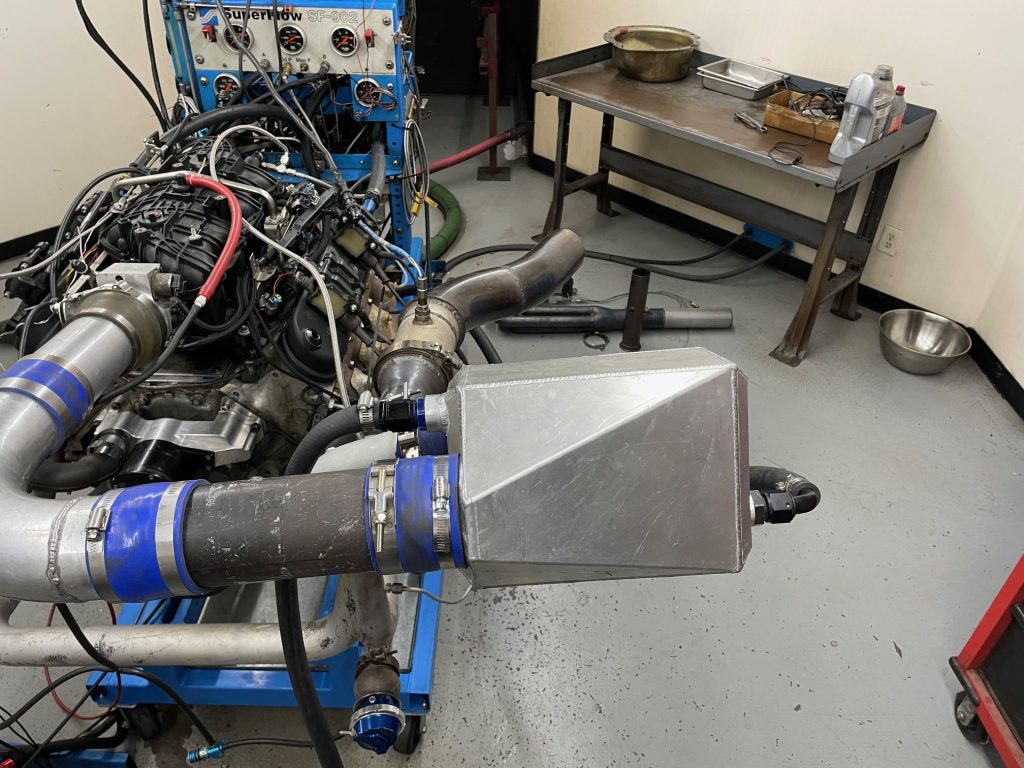

To facilitate this, we set up a unique system by feeding the turbo with only 1 side of the engine. Fear not, this asymmetrical design has been used in production vehicles (by Saab on a V6). Feeding the turbo with only ½ the exhaust flow meant the manifold would play a bigger part in response rate.

For those having a hard time understanding, all 8 cylinders were run under boost, but the turbo was only driven by the exhaust flow of half the motor (4 cylinders). The other side of the motor used a conventional header. If a normal turbo LS relies on exhaust flow from 8 cylinders and a supercharged LS relies on flow from 0 cylinders, think of this asymmetrical system as simply being between these two. The concept is not unlike using half of the motor to feed each turbo on a twin turbo set up! Trust us, it works, and the set up allowed us to isolate the effect of the different manifold designs on boost, but in no way should this stop you from making those comments.

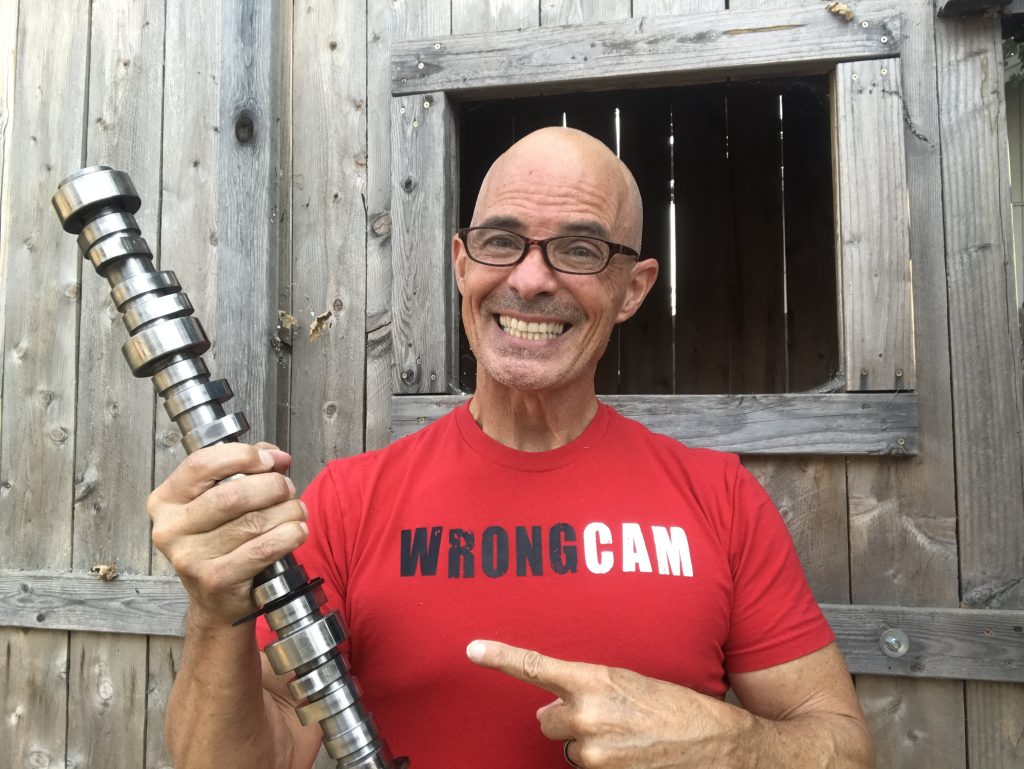

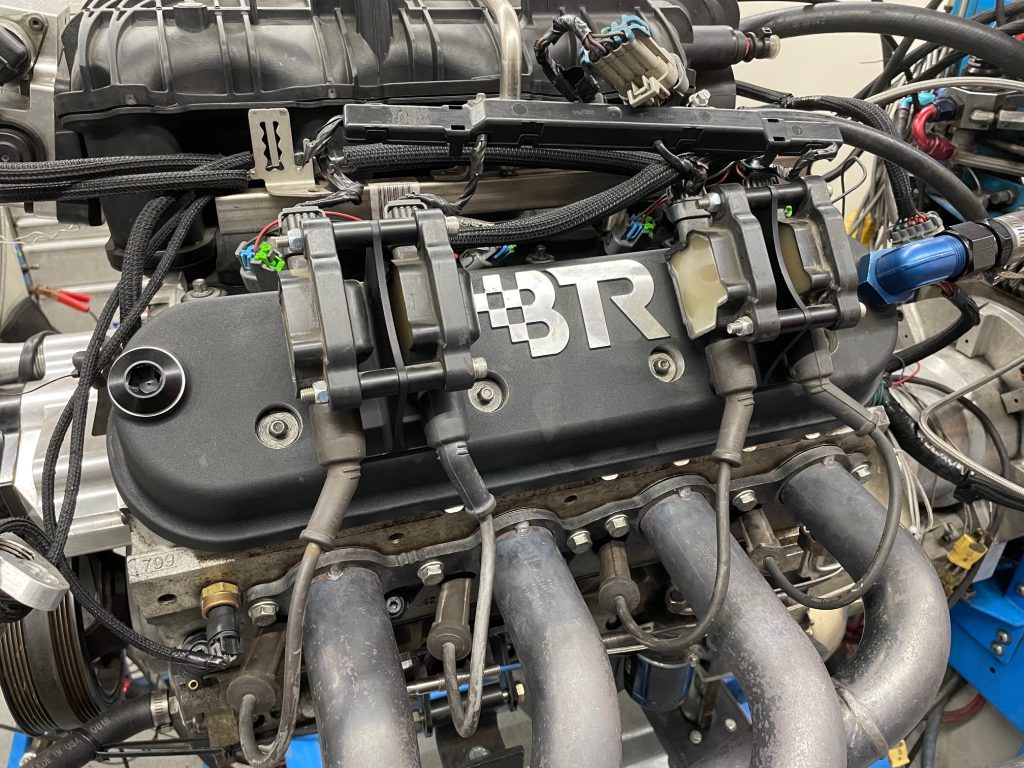

To compare the two different manifold designs, we equipped an aluminum 5.3L L33 with an RHP Low Buck Truck cam (could use hundreds of other cams as well), a TrailBlazer intake and 1,000cc injectors. All testing was run with a GTX3584RS turbo, a single Turbosmart wastegate, and Holley HP management system.

Each turbo set up ran the same air-to-water intercooler and E85 from our local pump. It is important to note that we essentially eliminated the waste as boost control by running the boost reference line to the top of the gate. The gate was closed throughout each test, meaning the asymmetrical turbo system was free to make as much power and boost as it could.

We first ran the FSP log-style manifold set up and the turbo motor responded with a rising boost curve, topping out at 175 kpa (11 psi), where the turbo 5.3L produced 710 hp and 668 lb.-ft. of torque.

We then replaced the FSP log-style manifold with a typical LS tube header (1-3/4 inch primary and 3 inch collector), using the same turbo, wastegate, and timing curve (A/F was kept at 11.5:1). Run with the larger tube header, the boost response was down from bottom to top, peaking at just 146 kpa (6.7 psi). This resulted in just 603 hp and 560 lb.-ft. of torque.

For boost response, the smaller log-style is tough to beat, but for max (4-digit) power, the tube header would likely still get the nod.

Comments