What can you tell me about the factory small block Chevy iron cylinder heads with the 492 casting number? I have a set of iron heads with screw-in studs, pushrod guide plates, Corvette valve springs (yellow paint), and big valves. They are on an engine in a 1934 Ford I bought. The previous owners told me that the engine was a 350, but it has a 4-inch bore and a 3-inch stroke which makes it a 302 engine. I don’t think it’s a DZ302 out of a Z28 because it has a hydraulic cam.

R.D.

Chevy switched from 302ci to 350ci engines for the Z28 Camaro in 1970. Based on your information the engine is 302 cubic inches, but it may have been built using a 327 block and a 283 crankshaft. You didn’t mention if it is a small or a large journal engine; the late 327s featured larger journals. It could also be built using a 0.125-inch overbored 283 block, taking it from a 3.875-inch bore out to 4.00 inches. More information could be determined by looking at the block casting number.

But your question relates to the 492 cylinder head. It was never built for production use; it was a replacement cylinder head offered by Chevrolet in the 1970s and beyond. It does have the distinctive “double hump” casting mark.

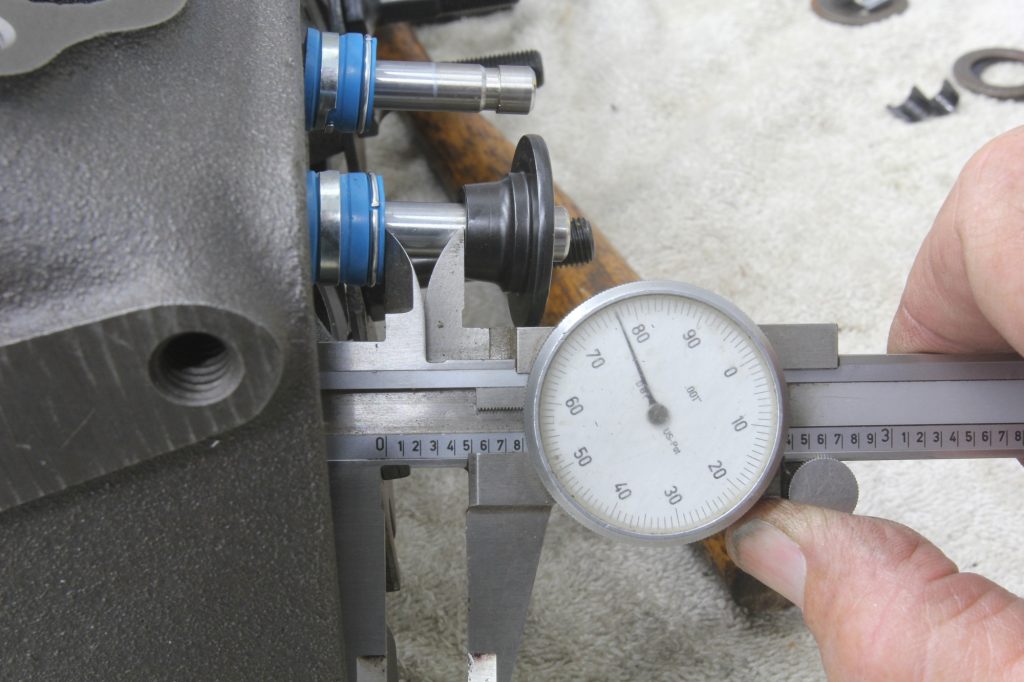

The 492 heads were produced with pressed-in studs, although it’s possible yours were converted to screw-in studs and guide plates. This was a very common conversion, especially when using bigger valve springs with higher spring loads. Screw-in studs don’t pull out of the casting during high RPM operation like pressed-in studs can.

The 492 heads came with either 1.94/1.50-inch or 2.02/1.60-inch diameter valves. The chamber size is 64cc, which helps boost compression. Despite their vaunted reputation, the flow numbers are not all that great. With the small valves, intake side flow numbers are anywhere from 200 to 210 CFM at 0.500-inch valve lift and around 150 CFM on the exhaust side at the same lift figure.

These heads can be pocket-ported to improve airflow, but the numbers are still not going to be as good as an aftermarket aluminum head like Trick Flow’s DHC™ 200. That head has 2.055/ 1.60-inch valves and flows 275 CFM on the intake side and 204 CFM on the exhaust at 0.500-inch valve lift.

Granted, the DHC 200 heads are not cheap, but neither is rebuilding a set of stock 492 heads. Machine work and parts to do this could run $1,000 or more. Here are some of the things you’ll need to have done:

- New valve guides installed

- Head deck surfacing

- Valve job

- Machining for positive valve guide seals

- New valves

- New valve springs set up for installed height

- New valve spring retainers and valve locks

Perhaps the heads are in great condition already and you plan to just bolt them on. I would still convert the valve guides to use quality positive seals instead of the stock O-rings that were marginal at best. Same with new valve springs unless you know the current springs are relatively new, have been load tested, and are compatible with the camshaft you plan to use.

This article is mostly correct with 1 exception. 1969 Z/28 DZ engines did use the 492 heads and the studs were pressed in. However the service replacement heads had screw in studs. I know because my DZ 302 had 1 head replaced under warranty. That head used the screw in studs. The original head did not.