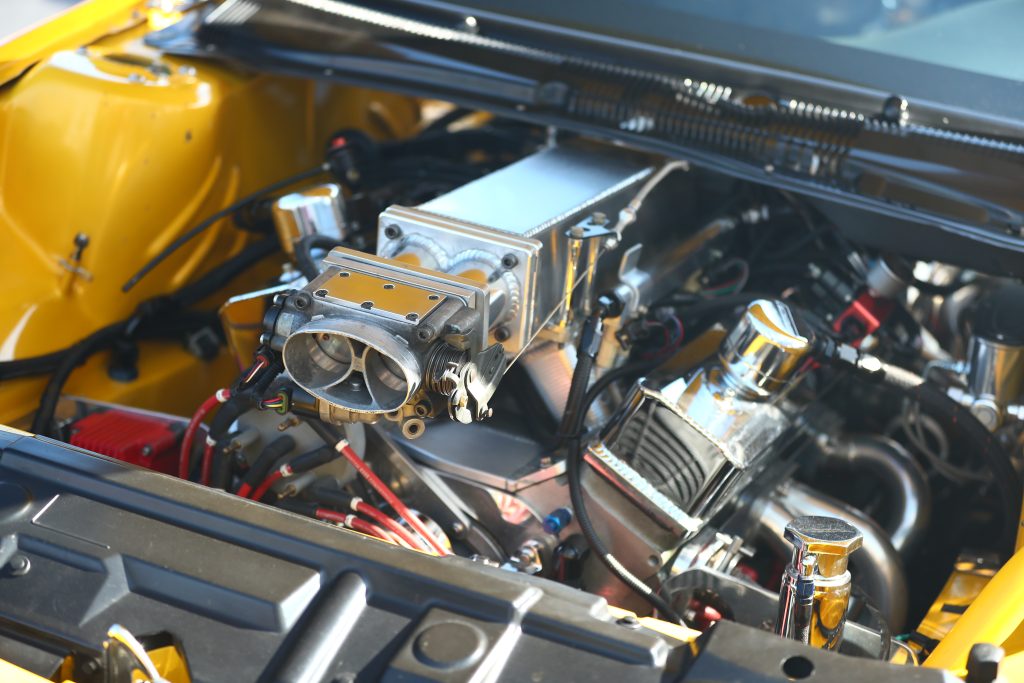

Pop the hood at any car show or racetrack and the first thing you typically see is the engine’s intake manifold. The intake is often one of the coolest parts of the powerplant, but more importantly, it’s a key component in feeding the air/fuel mixture to the cylinders.

Between carbureted intake manifolds and EFI intake manifolds, there are literally endless of options, sometimes even a dozen or more for a single engine type. The right intake will feed your engine in the most efficient manner and deliver great power in the range you desire. Additionally, an efficient intake will produce the best average output, which is critical, especially in street applications. Selecting the wrong manifold can result in flat performance when you hit the throttle.

Induction Science

You probably know the intake feeds the intake ports in the cylinder heads, but what makes the air flow?

The action begins when the piston is drawn down the bore on the intake stroke. As this occurs, pressure drops in that cylinder (in relation to the pressure in the intake manifold). When the intake valve opens, the air/fuel mixture rushes in because pressure naturally wants to equalize. There’s very little time to fill the cylinder, so the velocity of the column of air in the intake runner is important. The speed at which the column of air moves is dictated mainly by runner shape, size and length.

As a general rule, short runners are more efficient at filling the cylinders at high rpm; longer runners are generally more efficient at low to mid-range.

To create maximum efficiency for a given engine, engineers design manifolds with runner lengths, port shapes and with different plenum sizes to meet the needs of the application. In OE applications, engineers work within constraints of hood clearance, cylinder head inlet flange angles along with carburetor or throttle body location. Thusly, when selecting and intake, consider fitment for hood clearance, accessories or sensors that may be attached, material type and style as it relates to the actual design.

Over time there have been intake designs from mild to wild, all in the name of increased airflow. In almost every case, developers are faced with challenges based around carburetor placement, engine style (inline, 60-degree V, 90-degree V, opposed, etc.), plus other parameters such as hood clearance or class rules. Familiar designs include single-plane, dual-plane, and individual runner (IR). Of course there are other variants, including cross rams and tunnel rams, plus high- and low-rise intakes.

As you well know, increased airflow means the engine can burn more fuel and make more power. Therefore, the goal is to get more air into the cylinders so more fuel can be burned per engine cycle. But it’s not as easy as just installing an intake with giant runners.

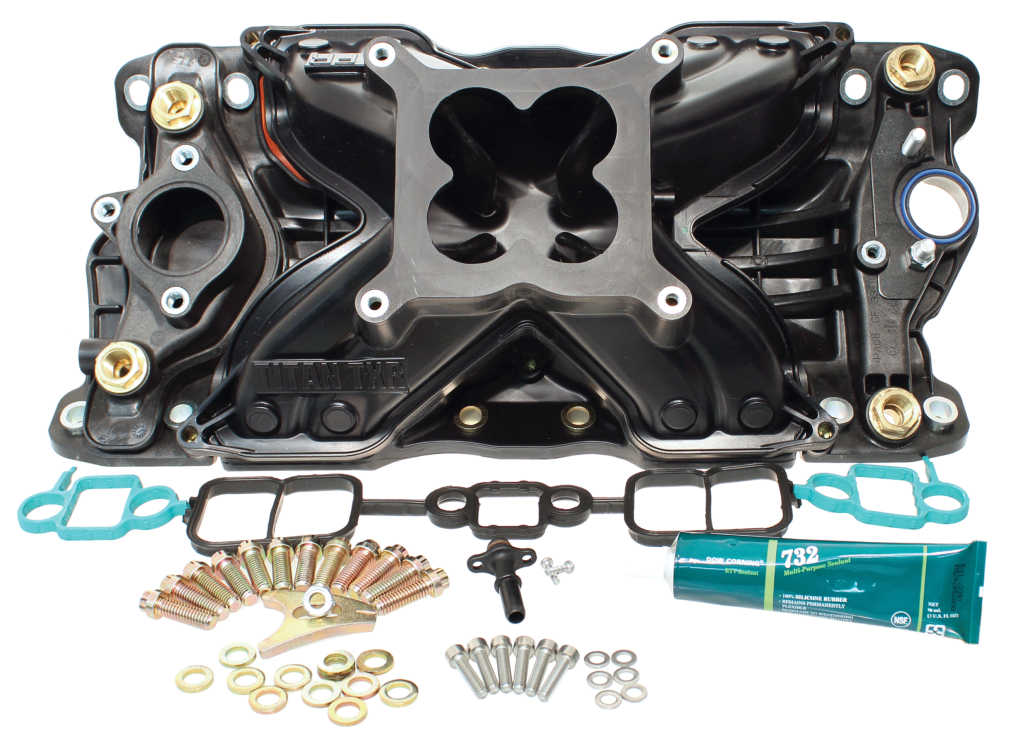

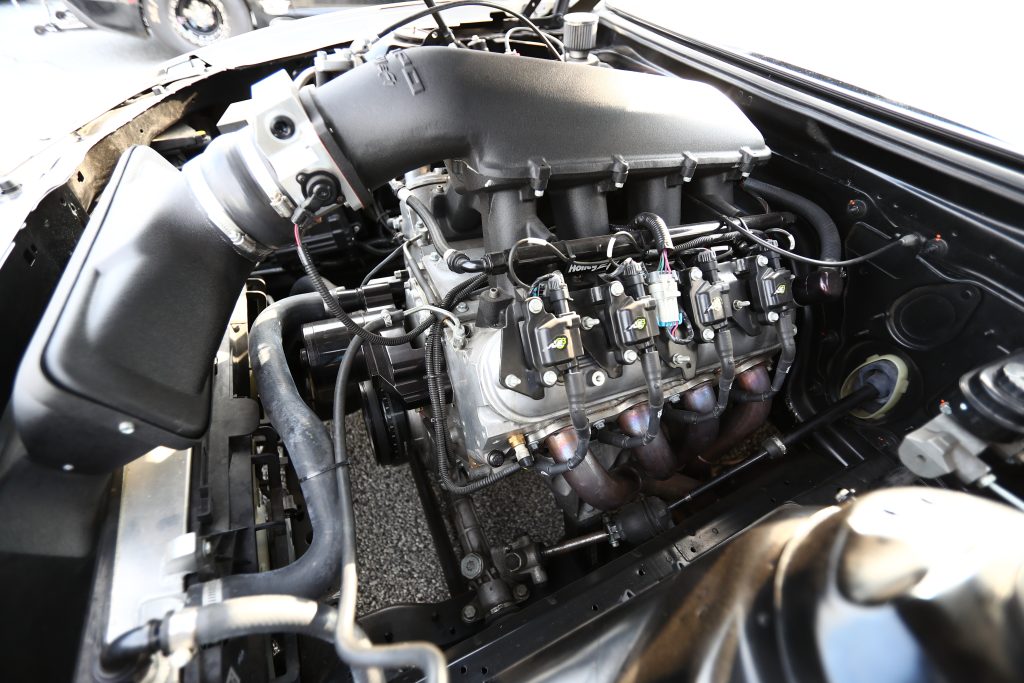

Most OEM (and many aftermarket) EFI manifolds found in production today are made from composite materials and incorporate individual runners with a common plenum. In drag racing, however, cast aluminum is the most common material. Reason being, it’s lighter than steel, it’s economical to manufacture, it’s easy to modify, and it dissipates heat nicely. Sheetmetal and billet aluminum are good choices, but they are more expensive to produce.

Plenum & Runners

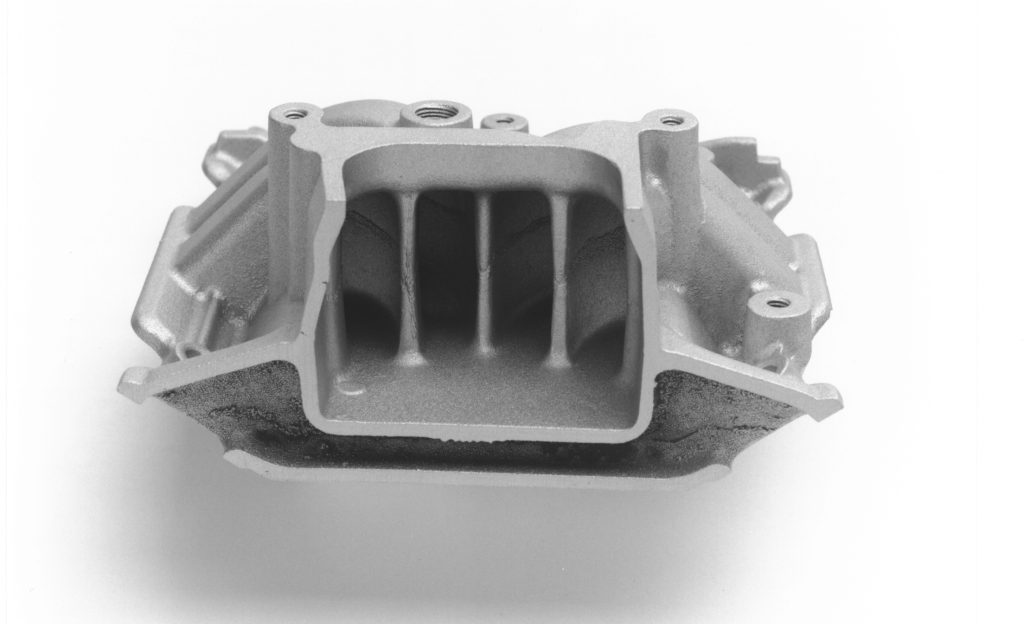

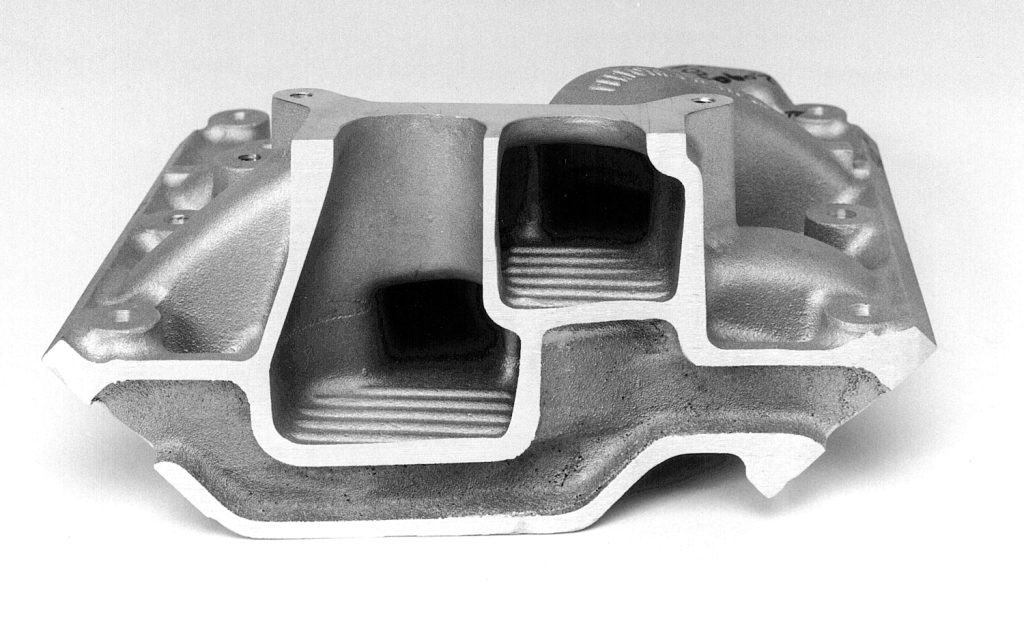

For any intake to be efficient it must be capable of providing adequate airflow for the displacement and rpm range of the engine. This requires properly sized plenum with runners that are matched to the powerplant.

“The runners are the brain of the intake,” said Tim Hogan of Hogan’s Racing Manifolds. “Changing the length and taper of the runners can move horsepower and torque peaks up or down as well as broaden your torque curve. When designing an intake, we look at tuning with the firing order, including changing cross-sectional areas of individual runners, entrance angles to cylinder heads, and most importantly changing velocity from runner to runner.”

Remember, the intake valve is open for just milliseconds, so in addition to volume, you need that column of air traveling in the intake runner to move at maximum velocity to achieve efficient cylinder filling. And as rpm increases, this window shrinks, placing more importance on the intake manifold runner design.

Get Your Fill

“Clearly, there is ‘magic’ in every manifold designer’s choice of runner taper and bell-mouth design,” said Billy Godbold, Valve Train Engineering Group Manager, COMP Performance Group (FAST, RHS, COMP Cams). “However, these fall into the last percent of performance and are not something people are really going to tell you. But choosing the proper cross-sectional area and length is incredibly important.

“The manifold exit cross-section needs to match the head entry very closely. Going over a small cliff is fine, but air doesn’t like hitting a wall. This is going to be the first consideration on the runner cross-section when designing a manifold for a given head. Then you go back to that taper magic to work back to the opening. Once you have the cross-section, the runner length can be chosen following three considerations,” he explained.

“You also have to look at Helmholtz resonance equations,” Godbold added. “This will give you the proper tuning lengths based on rpm and other engine configuration parameters.”

Remember, the column of air [in each runner] has momentum, and it’s still moving towards the cylinder when the intake valve shuts. When this occurs, the air slams into the valve and returns up the port, before it is pulled back when the intake valve opens again for that cylinder. Tuning runner length can take advantage of this resonance resulting in improved volumetric efficiency and power. You want to take that information and work around some simulation programs to further research how longer or shorter runners should shape the torque curve and change overall mass flow,” Godbold added. “Finally, you want to test numerous runner configurations to see exactly how the performance changes with different runners with different camshafts and exhaust systems.”

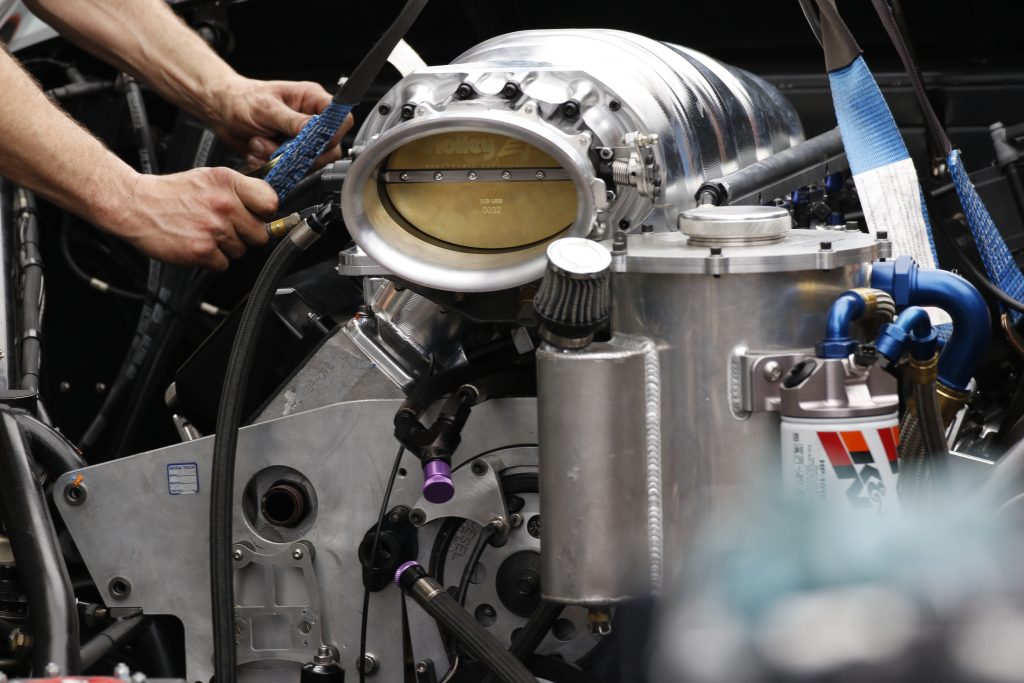

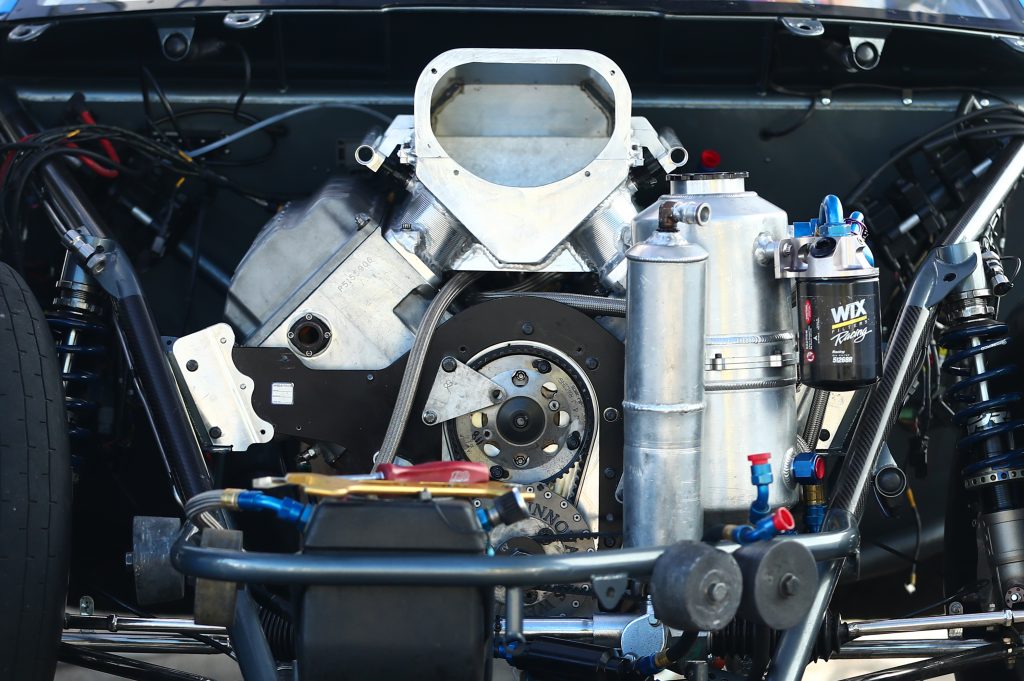

As far as drag racing goes, the perfect example of intake tuning can be seen in Pro Stock.

“NHRA Pro Stock has given us a great example of just how important it is to tune intake runner length to the rpm and cam timing events for any application,” said Godbold. “As rpm has been reduced to the currently mandated 10,500 rpm maximum spec, the intake runner lengths that were optimum for well over 11,000 didn’t work for proper shift recovery from the lower rpm.” You can also note the large plenum area needed to feed these 500-inch engines and the short runners that work best in the desired power range.

Manifold Materials

Racers do more than just select the type—they also look at materials. The process of 3d printing has given manufacturers the ability to design, build, and arrive at a finished product in hours, versus days or weeks. Composites also save weight and offer great resistance to heat. But composites are not suited for all combinations.

As we mentioned before, cast aluminum is still the most common material for aftermarket manifolds. This is due to cost and ease of manufacturing, plus they hold up well to boost. One example is the line of manifolds from Trick Flow Specialties and other air intake manifolds at SummitRacing.com.

“Make sure you aren’t just buying an intake to fit, but rather an intake for specific application,” said Tim Hogan. “Some of the biggest advances we have seen in recent years come in injector technology, as well as EFI systems. The tunability and power has accelerated so greatly in this area over the past five years. And we use mostly 6061-T6 for strength, machinability and lightweight.”

How To Select Your Intake

In most cases an aftermarket intake will likely produce more power than a stock unit. Factors to consider include displacement, camshaft specs, cylinder head flow, gearing, weight and desired rpm range. And don’t forget hood clearance.

Then you can ask, are the runners and cross section the appropriate for my application? Is the overall flow appropriate for my performance goals (including throttle area)? Is the plenum sized appropriately for my application? Are all the flow paths well laid out and are the bell mouths properly shaped?”

If you’re a footbrake racer shifting at 5,500 rpm, you aren’t doing yourself any favors by choosing a big single-plane intake designed for 8,000 rpm. Even if that engine makes the highest peak horsepower on the dyno with that intake, you’re potentially sacrificing average horsepower and torque, which is what helps get your car off the line and through the gears. Often, a good mid-rise dual-plane manifold will yield the most torque and horsepower through the rev range on your typical street-going or street-strip hot rod.

Ultimately, arriving at the best intake takes research and proper testing. R&D is educational, and to many, the learning process is part of the challenge. Thanks to technology, computer simulation, and years of experience, most manufacturers can get you home with off-the-shelf intakes that work quite well.

Do yall have a fuel injection system for a flathead V8? Just asking can’t hurt. Might give yall a good laugh